Lia Purpura, Skate’s Egg Case (detail), featured in AGNI 102

On Lowell

Robert Lowell knew I was not one of his devotees. I attended his famous “office hours” salon only a few times. Life Studies was not a book of central importance for me, though I respected it. I admired his writing, but not the way many of my Boston friends did. Among poets in his generation, poems by Elizabeth Bishop, Alan Dugan, and Allen Ginsberg meant more to me than Lowell’s. I think he probably sensed some of that.

To his credit, Lowell nevertheless was generous to me (as he was to many other young poets) just the same. In that generosity, and a kind of open, omnivorous curiosity, he was different from my dear teacher at Stanford, Yvor Winters. Like Lowell, Winters attracted followers—but Lowell seemed almost dismayed or a little bewildered by imitators; Winters seemed to want disciples: “Wintersians,” they were called.

A few years before I met Lowell, when I was still in California, I read his review of Winters’s Selected Poems. Lowell wrote that, for him, Winters’s poetry passed A. E. Housman’s test: he felt that if he recited it while he was shaving, he would cut himself. One thing Lowell and Winters shared, that I still revere in both of them, was a fiery devotion to the vocal essence of poetry: the work and interplay of sentences and lines, rhythm and pitch. The poetry in the sounds of the poetry, in a reader’s voice: neither page nor stage.

Winters criticizing the violence of Lowell’s enjambments, or Lowell admiring a poem in pentameter for its “drill-sergeant quality”: they shared that way of thinking, not matters of opinion but the matter itself, passionately engaged in the art and its vocal—call it “technical”—materials.

Lowell loved to talk about poetry and poems. His appetite for that kind of conversation seemed inexhaustible. It tended to be about historical poetry, mixed in with his contemporaries. When he asked you, what was Pope’s best work, it was as though he was talking about a living colleague…which in a way he was. He could be amusing about that same sort of thing. He described Julius Caesar’s entourage waiting in the street outside Cicero’s house while Caesar chatted up Cicero about writers.

“They talked about poetry,” said Lowell in his peculiar drawl. “Caesar asked Cicero what he thought of Jim Dickey.”

His considerable comic gift had to do with a humor of self and incongruity, rather than wit. More surreal than donnish. He had a memorable conversation with my daughter Caroline when she was six years old. A tall, bespectacled man with a fringe of long gray hair came into her living room, with a certain air.

“You look like somebody famous,” she said to him, “but I can’t remember who.”

“Do I?”

“Yes…now I remember!— Benjamin Franklin.”

“He was a terrible man, just awful.”

“Or no, I don’t mean Benjamin Franklin. I mean you look like a Christmas ornament my friend Heather made out of Play-Doh, that looked like Benjamin Franklin.”

That left Robert Lowell with nothing to do but repeat himself:

“Well, he was a terrible man.”

That silly conversation suggests the kind of social static or weirdness the man generated. It also happens to exemplify his peculiar largeness of mind…even, in a way, his engagement with the past. When he died, I realized that a large vacuum had appeared at the center of the world I knew.

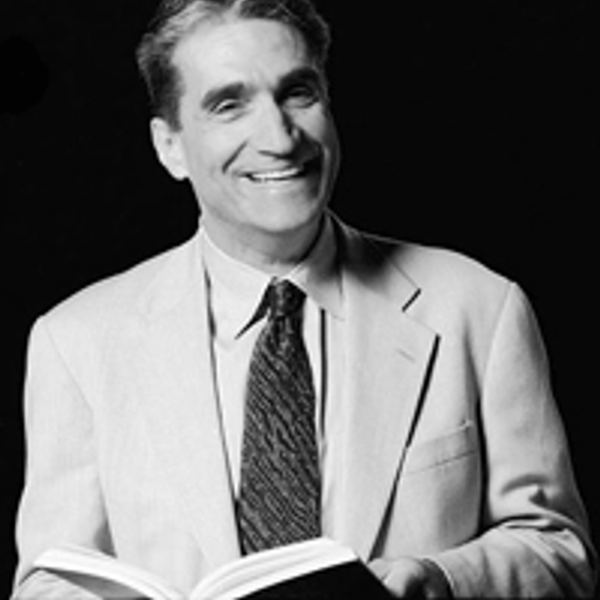

Robert Pinsky

Robert Pinsky, the author of the memoir Jersey Breaks: Becoming an American Poet (W.W. Norton, 2022), served as poet laureate of the United States from 1997 to 2000. During his tenure he created the Favorite Poem Project to document, promote, and celebrate poetry’s place in American culture. In addition to three anthologies co-edited by Pinsky, Americans’ Favorite Poems, Poems to Read, and An Invitation to Poetry, the project has produced fifty short documentaries showcasing Americans reading and speaking about poems they love.

He has published ten collections of his own poetry, most recently Proverbs of Limbo (2024) and At the Foundling Hospital (2016), both from Farrar, Straus & Giroux. The Figured Wheel: New and Collected Poems 1966-1996 was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and received both the Lenore Marshall Award and the Ambassador Book Award of the English Speaking Union. His other awards include the Shelley Memorial Award, the William Carlos Williams Prize, the PEN/Voelcker Award, the Korean Manhae Award, and the Los Angeles Times Book Award, as well as the Howard Morton Landon Translation Prize for his bestselling verse translation of The Inferno of Dante. Among his other prose works are The Sounds of Poetry: A Brief Guide and Thousands of Broadways: Dreams and Nightmares of the American Small Town. Poemjazz, his CD with pianist Laurence Hobgood, is available from Circumstantial Productions.

Pinsky directs the graduate creative writing program at Boston University and is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and AGNI’s Advisory Board.

Pinsky’s collections Poetry and the World and The Want Bone were reviewed in AGNI 36 by Peter Sacks. His translation of The Inferno was reviewed in AGNI 41 by Alfred Corn. Pinsky’s collection The Figured Wheel: New and Collected Poems was reviewed in AGNI 44 by Thom Gunn. (updated 4/2025)