Lia Purpura, Wasp Nest (detail), featured in AGNI 102

Jury Duty

In the jury room everyone was looking at the middle-aged man in the suit and tie, the man they’d selected to serve as their foreman, and who was now presenting problems they had not thought to think about and that they didn’t really want to consider considering. They had all been watching the clock and wondering how long they might be there, for what, they’d thought, was an open-and-shut case. The facts were clear enough, no one disputed that, and they had listened as carefully as they knew how, and heard what the judge had told them, and thought about it all, and imagined that they could work out anything still confusing in the jury room they’d been led off to. There was water and coffee and pens and paper, and they were told that they would be able to ask for any other things they needed to make their deliberations move forward smoothly, with deliberate speed, as the judge had informed them. They sat around the oval table and looked at each other now really for the first time since early that morning when they’d been asked to take their seats in the jury box and they’d stared at one another somewhat uneasily. But then they’d concentrated on what was going on in front of them, what the judge was doing behind his high carved bench and what the lawyers (who were, they’d noticed, calling themselves attorneys) said, and the way they said it, and how they moved around their tables and sat and stood and often turned to look at them, and how they sometimes seemed to focus on one or another of them in particular, and how they all watched the judge closely, even when he didn’t seem to be listening to what they were saying. Even though one or another of them seemed to be occasionally confused, the judge, who noticed everything (although he pretended not to) had told them that he would explain anything they wanted to know later on, if they asked him to. Anyhow, they all thought that at least one of them—the sad-seeming man in the gray suit and the yellow tie that they’d chosen as their foreman—probably did understand everything that had been said, and also everything that was going on, even though the lawyers never seemed to look directly at him and one of them seemed to be angry that he was even there in the jury box with the rest of them. What they’d heard and what they thought they understood was that the defendant, the young man in the blue shirt too big for him and with eyes that seemed almost too closely set together and that shifted back and forth along the line of their faces in the jury box—as if he might be thinking about which one of them he would kill first, if he had the chance, if he was free and they were still out there—what they were told was that the defendant was guilty Your Honor of the cold-blooded murder of an old innocent couple who’d never harmed anybody or anything in their whole long-married lives. And they were also told that the red pickup truck that had been parked in front of the house was quite possibly a decoy, something to lure the victims into the house, since it was well known that the elderly couple’s son (who had mysteriously disappeared more than a week before the murders, and who would have been the only one to know where what was thought to be a large sum of money was hidden) had a red pickup truck similar to the one that had been parked in front of the house. These details about the crime scene, as it was being called by the lawyers, had been firmly established and corroborated by several police officers. But whether the case was to be based exclusively on such circumstantial evidence (which the judge, reading from a sheet of paper, had described as evidence that proves a fact by proving other events or circumstances that force an inference of the occurrence of the fact suggested) or not, none of them seemed to know for certain. And what they were told was that the young man, the defendant, yes Your Honor, had planned it all perfectly, and had almost carried it off too, even if he hadn’t apparently gotten any of the money. The old couple were dead and their son, or his body, had never been found. The only remaining mystery was that the pickup truck had finally been found at a different location, abandoned on a dirt road more than three miles from the scene of the crime. How that had happened, and who might have been responsible for moving it, was the crux of the matter. And one of them—after their foreman said that it was impossible that that truck could have flown through the air and landed there on that dirt road under the overhang of an old oak tree all on its own—just snorted and turned his head away and said that that was just the kind of thing a city college boy might say, and several of the women nodded, as if they too thought that it might be true, or at least possible. And then the foreman, who had seemed to sigh, and had once or twice covered his eyes with his hand, as if he were tired, looked around the table again at each of them in turn, and asked whether any of the rest of them really thought that it was possible, whether they believed in magic or some mysterious power that could lift a two-ton truck straight up into the air from a shaded street in the city and drop it down on a deserted dirt road several miles out of town. Most of them hadn’t thought about it exactly that way, but when he suggested it, some of them thought that it was possible, and, if that were the case, that, therefore, the young man in the pale blue shirt unbuttoned half way down to his navel, and with his shifty brown eyes, was innocent, that he had been framed, as one of the lawyers had been saying all along; and they, because they now believed so strongly in this possibility, tried to convince some of the others that it was not out of the question—that it was not only possible, but plausible-even, someone said quite likely—and that if they all said so the judge would have to believe them and let the young man in the wrinkled shirt and tennis shoes go home, and then they could also go home in time for supper and for whatever shows they watched on television on Tuesdays, and then they wouldn’t have to think about it ever again, unless the young man came looking for them, some year or other, for whatever reason—none that any of them could think of at the moment. The judge and the lawyers had been talking a lot about circumstantial evidence, and reasonable doubts, and things that were beyond any reasonable doubts, and now the gentle man that they had chosen as their foreman, the man with the faded gray suit and the frazzled yellow tie, was asking them questions and looking at each of them in turn, the way the defendant and the lawyers had. Did they, he said, really believe that a red truck weighing more than a ton—that a truck of any color or whatever weight, could be lifted up by some sort of unseen power and transported more than three miles before being mysteriously and abruptly dropped down in the middle of nowhere, under a live oak tree that must have been more than one hundred years old—and that that meant that the young man there in the courtroom (in the faded shirt and untied tennis shoes, his hands constantly fisting upon one another, the one occasionally pounding into the other) was innocent and should be set free, and that they wouldn’t ever need to worry that he would come looking for them a few years from now, some night when they were alone, watching television, or even asleep, and they would get caught off guard, or be lured into a trap, as that old couple must have been? Then they considered it all all over again and most of them decided that it had, or could have, happened the way one of the lawyers (the one representing the young man, who never seemed to sweat the way his attorney did) had said—that it really could have happened in exactly the way that his lawyer said it had—that that young man, the defendant, yes Your Honor, was somewhere else entirely that night, minding his own business: that he couldn’t have been in two places at once and that therefore he couldn’t possibly have been at the scene of the crime, or moved the truck, or killed the old couple, that he was as innocent Ladies and Gentlemen of the Jury as any of them were. Most of them were almost ready to say that that was so, so that the judge would let them go home to see what was on the television, even if Tuesdays had none of their favorite shows on anymore. But the man in the wrinkled gray suit and the awkwardly tied tie, the only one who had thought to bring a tie along, even if they’d had one—John, he’d said his name was—said that he couldn’t buy that, that it didn’t hold water or make much sense at all. Who does he think we are, he said, to say that? Do any of you really think, he said, looking at them in turn again, that a two-ton truck could fly three miles through the air on its own? They all looked at each other again and more than half of them nodded, and somebody said they should stop this talk right then and there and take a vote and that that would settle it and they could all home and watch television. So John took out a pen and asked them to raise their hands, and they did, and the vote was ten to two, the two being John and an old woman in a purple dress with lace around the collar and the cuffs, who had been silent the whole time. She sat at the end of the table and looked down most of the time, so that some of them wondered if she was asleep (her hands always in her lap, and her glasses balanced on the end of her long nose), but then she suddenly looked up, pushed her glasses up with a quick gesture, and blinked at them. Then, staring at each of them in turn, and even pointing her finger at them several times, she said softly, No, of course not. That couldn’t have happened. That is absolutely preposterous. That young man is as guilty as guilty is. How could any of you think otherwise? And then she dropped her eyes and folded her hands in her lap again, and quickly closed her eyes, as if she was suddenly tired and wanted to go to sleep. The foreman seemed pleased, and he smiled slightly at the small woman with the huge black shoes, and then he looked around at them again, as if to ask them what they all thought about that. The clock ticked loudly and no one said anything for a long while and then it was already four o’clock. They could see the guard outside the jury room pacing back and forth in front of the door and looking in each time he passed the glass window. Once he seemed to make a point of looking at his watch as he passed the door, and he seemed to sigh when he saw that they were still sitting there. They knew that the judge and the lawyers were all waiting for them to reach a decision, to come to some conclusion and to let them know it, so that they all could go home and watch whatever was on on Tuesdays. The foreman reminded them that they needed to reach a unanimous decision, that they had to be certain that what they decided could be proven beyond a reasonable doubt and that there was really no rush, that they would be given a dinner and a place to sleep and they could come back tomorrow and try to reach their decision then. This trial, he said—glancing around the room and then at some of them specifically—is rather a complicated one, and some of the evidence isn’t as clear as it might really be (and he smiled weakly when he said that), and he added that the attorneys seemed to have purposely tried to confuse them (and as he said that he looked around the table very slowly again and at each of them) but what is most important, he said finally, is that they needed to come to the correct decision, because, he said, that young man’s life was hanging in the balance, and that, if it were their lives that were at risk, they would want their jury to be as careful, and as considerate, in two senses he said, as possible, and to render their decision, after all due deliberations (as the judge had told them to) as if that young man out there were a son of every one of them. They all agreed to most of what he said about doing their duty and all, but then he went back to the truck and started in again on how a large red pickup truck could mysteriously have moved from one place to another without going on its own power, without someone moving it between the two places—that something was really fishy about that whole story, the one that they had been told to believe in. And he reminded them that the young man in the dirty shirt with the shifty eyes and torn tennis shoes seemed to pound his hand every time the prosecuting attorney looked at him. The foreman said that that was a kind of intimidation and that they shouldn’t be a party to anything like that, that they should do their duty and render a just verdict, just as the judge had told them to, and that they should take as long as they needed to—that, if at all possible, they didn’t want to be a hung jury and then have to have somebody else do all of this all over again, with that rusty red pickup truck still hanging there in midair as it were.

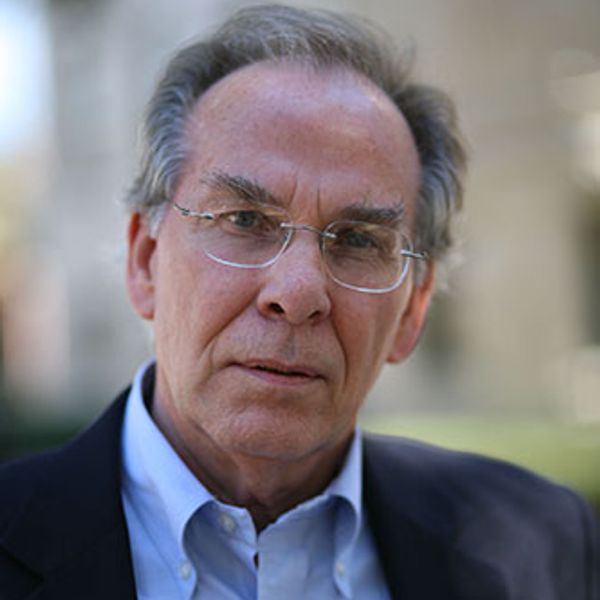

William Virgil Davis

William Virgil Davis is the author of six poetry collections, most recently Dismantlements of Silence: Poems Selected and New (2015). His other titles include The Bones Poems (2014); Landscape and Journey (2009), winner of the New Criterion Poetry Prize and the Helen C. Smith Memorial Award for Poetry; One Way to Reconstruct the Scene (Yale University Press, 1980), which won the Yale Series of Younger Poets Prize; The Dark Hours (which won the Calliope Press Chapbook Prize); and Winter Light (University of North Dakota Press, 1990). His poems have appeared in Poetry, The Nation, The Atlantic Monthly, AGNI, The Southern Review, and elsewhere; his short fiction in, among other magazines, Confrontation, The Malahat Review, New Orleans Review, and The Windsor Review. He has also published six books of literary criticism, most recently R. S. Thomas: Poetry and Theology. He is professor of English and writer-in-residence at Baylor University. (updated 10/2018)