Lia Purpura, Parasol Mushroom (detail), featured in AGNI 102

More on the Invention of Drawing

Translated from the French by Hoyt Rogers

Say what you will, drawing the shape of your lover on the wall is no easy task when he’s lying on the same bed as you. Even with her chalk in hand, the young girl hates to let go of him, and still enfolds him in one of her arms. On top of that, the boy keeps moving: he bothers her, he distracts her, he makes her forget her work. And so the lamp placed behind the bed casts shadows of them both on the beautiful blank expanse—outlandish shadows that never stop shifting. In such utter disarray, try if you can to trace the curve of a shoulder on the faintly dimpled whitewash, with no more than a piece of chalk.

This explains the future history of drawing, otherwise impossible to grasp. The daughter of the Corinthian potter attempts to sketch quickly, wedding her stroke to this silhouette which means a shoulder—or a hip, for all I know. But in fact her line veers away from the contour, plunges into the shadow’s heart and lingers there; it emerges only with regret, pursued by a thought that seems hard to shake off. Instead of proceeding toward the arm—this raised arm, this hand held out as if to touch the image on the nearby wall—she who merely wanted to master a line is now drawing . . . what? A sort of tree, branches that fork in all directions, numberless birds that fly through a storm-swept sky, with a gamut of feeble cries.

Her sole intent was to remember a shape. And she finds herself imagining, feeling, dreaming . . . yes, how wonderful, for a moment. The entire history of drawing, and even that of painting, will derive from this. But she has to get back to work; she’s pressed for time. Soon he will be leaving, and the girl wants so much to store up her memory of him. “Please, don’t move any more!”

Come now . . . He takes the hands of this budding artist in his own and gently pries her fingers apart. He sets the stub of chalk on the nearby table—that table where through the centuries, the lamp burns on.

Yves Bonnefoy, often acclaimed as France’s greatest living poet, has published ten major collections of poetry in prose and verse, several books of tales, and numerous studies of literature and art. He succeeded Roland Barthes in the Chair of Comparative Poetics at the Collège de France. His work has been translated into scores of languages, and he is a celebrated translator of Shakespeare, Yeats, Keats, and Leopardi. Most recently, he has added to his long list of honors the European Prize for Poetry (2006) and the Kafka Prize (2007). He lives in Paris. (11/2012)

Hoyt Rogers has published over a dozen books, including his own works as well as translations from the French, German, and Spanish. His versions of Borges appeared in the Viking Centenary Edition. His most recent translation from the French, Second Simplicity—verse and prose by Yves Bonnefoy—was published by Yale University Press this year. With Paul Auster, he is currently translating Openwork, an anthology of poems by André du Bouchet. He divides his time between the Dominican Republic and Italy. (11/2012)

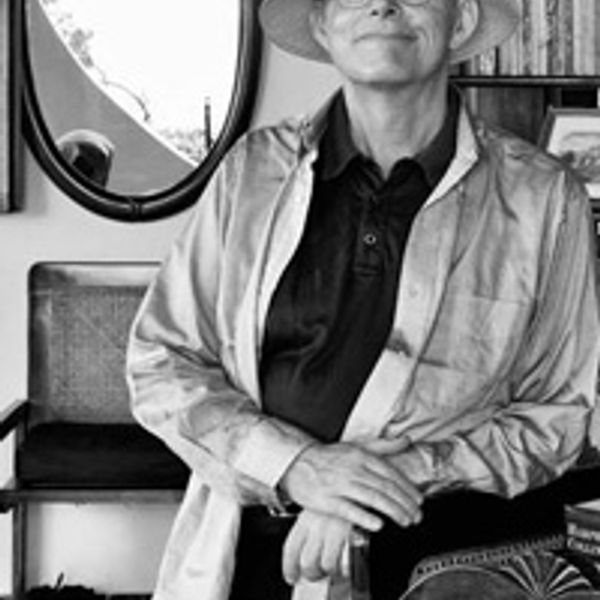

Yves Bonnefoy

Yves Bonnefoy (1923–2016) is often acclaimed as one of France’s greatest poets. He published ten major collections of verse, several books of tales, and numerous studies of literature and art, and was a celebrated translator of Shakespeare, Yeats, Keats, and Leopardi. His work has been translated into scores of languages, and he earned many honors, including the European Prize for Poetry (2006) and the Kafka Prize (2007). He succeeded Roland Barthes in the Chair of Comparative Poetics at the Collège de France.

Hoyt Rogers

Hoyt Rogers’s forthcoming works include Sailing to Noon, the first novel in The Caribbean Trilogy (with Artemisia Vento). He is the author of the poetry collection Witnesses and book of criticism The Poetics of Inconstancy. His poems, stories, and essays have appeared in New England Review, The Antioch Review, AGNI, The Fortnightly Review, and dozens of other publications. Rogers also translates from French, German, Italian, and Spanish. He has translated four books by Yves Bonnefoy, most recently Rome, 1630 (Seagull Books, 2020), which won the French American Foundation’s Translation Prize. He translated and edited, with Paul Auster, an anthology of poems and journal entries by André du Bouchet, Openwork (Yale University Press, 2013); and with Eric Fishman, he translated du Bouchet’s Outside (Bitter Oleander Press, 2020). (updated 10/2021)