Lia Purpura, Parasol Mushroom (detail), featured in AGNI 102

At the Dawn of Time

Translated from the French by Hoyt Rogers

I come back to the house of the long-ago past. And I am amazed to find its spaces vaster than I recalled—starting with the staircase, the part that was clearest in my memory. From our upper floor, I used to go there each morning and sit on the steps, in the feeble light that filtered through the entrance hall’s thick door. I always enjoyed the coolness at the hottest hour of the day. One time I fell there, and my father was frightened; he shouted and took me in his arms.

But I didn’t remember the steps as being so gradual and wide, of such massive gray stone, nor as sweeping this majestically up to the attic—though I retreated there quite often to read. You don’t go up to the attic like that in ordinary houses. Now I grasp that the house isn’t of this world—that it was laid out in another era, elsewhere. And I can almost see beings from that elsewhere grouped around a table. Under their eyes are surveys and maps, immense horizons of long limestone hills. They look at them, absorbed in thought. One of them puts his finger on a survey map, right where two little children, a boy and a girl, are quarreling over an object. You can barely pick it out on this old photograph: is it a small animal they’re holding in their arms? A small life with jerky movements and mewling cries, part of the body of one or the other, or of both? Or was it an entire swath of the enormous starry sky? That morning, the tide of the summer day, though rising, hadn’t yet effaced it. I don’t know what they held there, which they let get away; but now I watch them climb back up the staircase, hand in hand.

Nor have I forgotten that this attic—a low construction of heavy timber, hot and odorous, with a floor of badly joined planks—had served for many years as the final resting place of trunks, left open because they overflowed with old magazines and books. Many of them lay about in messy piles, with numerous volumes of I Know Everything, the “Illustrated World Encyclopedia.” The first page showed a little man dressed in black, his head the terrestrial globe. With a finger—how appalling!—he touches his forehead, his eyes lost in his dream. Kneeling before a trunk, I spend hours reading I Know Everything. I contemplate from afar, through sooty lithographs, the shores of Polynesia, with their beautiful, half-naked beings; or dreadful nocturnal rooms, scarcely illumined by oil lamps, where heads throng in a circle of light—though who they are I will never know.

Yves Bonnefoy died this month. Often acclaimed as one of France’s greatest poets, he published ten major collections of verse, several books of tales, and numerous studies of literature and art. His work has been translated into scores of languages and won many international awards. He is also a celebrated translator of Shakespeare, Yeats, Keats, and Leopardi. He succeeded Roland Barthes in the Chair of Comparative Poetics at the Collège de France. His latest poetry collection is Ensemble Encore (Together Still). (7/2016)

Hoyt Rogers has published a poetry collection, Witnesses, and a volume of criticism, The Poetics of Inconstancy. His fiction, poetry, and essays have appeared in a wide variety of periodicals and anthologies. He translates from the French, German, Italian, and Spanish. He has translated three books by Yves Bonnefoy: The Curved Planks (Farrar, Straus & Giroux), Second Simplicity (Yale University Press), and The Digamma (Seagull Books). Two more works by Bonnefoy, Together Still and Rome 1630, are forthcoming at Seagull. (7/2016)

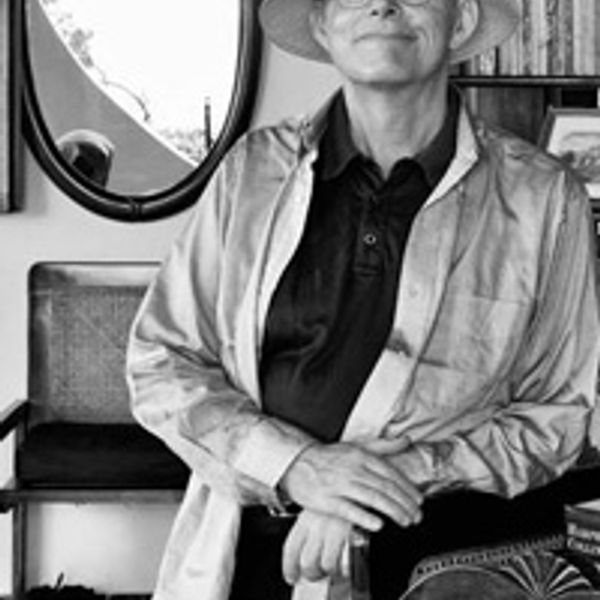

Yves Bonnefoy

Yves Bonnefoy (1923–2016) is often acclaimed as one of France’s greatest poets. He published ten major collections of verse, several books of tales, and numerous studies of literature and art, and was a celebrated translator of Shakespeare, Yeats, Keats, and Leopardi. His work has been translated into scores of languages, and he earned many honors, including the European Prize for Poetry (2006) and the Kafka Prize (2007). He succeeded Roland Barthes in the Chair of Comparative Poetics at the Collège de France.

Hoyt Rogers

Hoyt Rogers’s forthcoming works include Sailing to Noon, the first novel in The Caribbean Trilogy (with Artemisia Vento). He is the author of the poetry collection Witnesses and book of criticism The Poetics of Inconstancy. His poems, stories, and essays have appeared in New England Review, The Antioch Review, AGNI, The Fortnightly Review, and dozens of other publications. Rogers also translates from French, German, Italian, and Spanish. He has translated four books by Yves Bonnefoy, most recently Rome, 1630 (Seagull Books, 2020), which won the French American Foundation’s Translation Prize. He translated and edited, with Paul Auster, an anthology of poems and journal entries by André du Bouchet, Openwork (Yale University Press, 2013); and with Eric Fishman, he translated du Bouchet’s Outside (Bitter Oleander Press, 2020). (updated 10/2021)