Lia Purpura, Wasp Nest (detail), featured in AGNI 102

Somewhere Close to the Start of the Game (Foosball)

A market evening in a small coastal town on the south bank of the Red Sea. A gathering on the main square, shrouded in darkness—a town that lives to the rhythm of the night tides. The monsoon, with its Indian winds and its cartloads of dark clouds, is at the gates of the city. Soon it will rain hard for a few days or even a week or two, if Allah the Most Merciful is kind to us.

Night and day, the cattle merchants stand or squat on their heels, feeling the rumps of the animals about to be shipped to the other bank of the Red Sea. From time to time, they lean over to spit out juice from their quid as their eyes and hands size up sheep, rams, kids, cows, and calves with meditative detachment.

The least attractive animals go nowhere and end up in stews in cheap eateries. They’re carved up on the beach right away, through rain or wind or dark of night. A cloud of flies immediately covers their carcasses like a new skin, coal-black and swarming with life. Starving cats feast on their guts, unceremoniously dumped here and there on the muck of the beach between the pirogues that have been pulled onto dry land. Mysterious three-toed footprints come from the chickens that strut around on the sand from dawn on.

~

This evening is not an evening like any other. Mist is beginning to veil the sun. A mist from the Gulf of Oman or the Indian Ocean has surely stroked your skin if you have just arrived in our little town. Tonight, another event is on everybody’s mind—not the caravanserai, cattle trading, and three-toed footprints. Tonight there’s a crowd on the main square. It feels good to be a crowd. It feels good to be a pack. Rumors swirl over the big mosque. The atmosphere is enchanting. The sound of a reed flute rises to heaven under a salvo of benedictions addressed to the Lord. Words alternating with long silences, singing, notes, and maxims rise and float upwards, bouncing off the dome of the mosque, then vanishing into the boundless canopy of heaven. An angel flies by, followed by his elongated shadow. Silence. In the middle of the crowd, a little man with slumping shoulders and a flute in his mouth is attracting every gaze. The one they call the Beggar Saint—behind his back, of course—looks mournfully over the crowd, his wet eyes not focusing on any precise face, not even on the bare-chested children running with a rag soccer ball at their feet from one point to another in the great human circle that fills the open square.

The bewitching sound of the flute winds through the air. It lifts the hearts of the men assembled on the big square, all of them alerted by an order from elsewhere or just by chance. A stone’s throw away, another gathering seems to be breaking up. The cattle merchants, who are fiendishly clever, talk about this and that, but never miss a chance to interrupt the shepherds, whose legs are worn out from walking. Some nomads, tired of bargaining, give up and take shelter in dark joints where a plate of sticky rice costs an arm and a leg, though theirs are rather skinny.

As for the crowd, it is waiting for the flutist to catch his divine breath.

The youngest spectators are growing impatient. They can already picture themselves in Diriyeh’s courtyard, in front of the only TV in town, watching the finals of the Africa Cup of Nations. The Egyptian Eagles are taking on the Ivory Coast Lions, they whisper, led by Didier Drogba at the top of his game. Right before the half, as the adults get more and more excited—the rush of blood to the brain may explain their excitement—they’ll send out their kids one after the other for bottles of Pepsi and Mirinda at the Mashallah grocery. The kids will rush back with the sodas for their parents, hurrying so as not to miss one second of the game, stumbling in the dark paths, part ravine and part sidewalk. The second half will start at the same tempo as the first. Again the crowd will forget the little man with sloping shoulders who—for a change—sticks an imaginary violin under his chin. The instrument gives out a melancholy tune.

~

Now, half an hour before the beginning of the game, a dense crowd has already gathered in front of the grocery. There is communion in the peaceful evening. Someone throws an old proverb into the air. A lady picks it up on the fly. Her neighbor looks her right in the eye before signaling that he gets it without her having to spell things out. “Let’s not lament that time is fleeting; we exist and that is quite enough. Let’s see how the game ends up, and the rest can wait!” That’s what these two people seem to be saying to each other. Their words are traveling in the wake of the sinuous notes of the flute (or is it the invisible violin?), linking its melodies; the piece of reed connects their lips, holding their bodies together as one resounding surface. The reed flute carries across the starry spaces, and like stories that pass from one mouth to another, sometimes coming back through the same mouth to make their way into the neighbor’s ear, the waves never die.

~

Many years ago, an important businessman of the city, Somali by birth, got the idea of competing with the richest man in the land, who was of Arab descent. The latter had quickly gained favor with the authorities in the capital; and as is customary in our land, he already owned several licenses, particularly for importing Coca-Cola products. The Somali saw his business prosper for a while: his new import license for Pepsi-Cola products earned him more and more money, despite the unfair competition of the Coca-Cola distributor. The latest word is that the Somali is out of favor with the powers that be, his business is failing and he is afraid of going under. Fear, anger, and a desire for vengeance have got hold of this big businessman, who supports a whole bunch of unemployed people. Fear of joining the beggars’ ranks, of holding out the begging bowl himself, of ending his days in the mud, drowned in the spit of the horse traders. Fear of seeing the house of Pepsi knocked out once and for all by Coke. The two American giants make life difficult for each other through their respective pawns.

An atmosphere of insurrection reigns at the gates of the little coastal town. Any argument is a pretext for throwing oil on the flames. Coca-Cola and Fanta are seen as symbols of foreign subversion, the armed branch of the Crusaders and non-natives who are sucking the country’s blood. Pepsi and Mirinda turn out to be authentic, native products, introduced by a son of our nomad country. The people will recognize its own even in the depths of night. Of course Pepsi is favored by the Mashallah grocery, run by a true citizen of pure nomadic blood, not one of those effeminate Arabs who go around wiggling their rumps. If Drogba beats the Egyptians, everyone will be wild with joy.

Many teenagers like to go to the grocery for its old-fashioned foosball table. They make a devilish din. They tell each other stories that could bring tears to your eyes. Don’t listen to them, or you run the risk of filling your ears with indelible filth. When you pass by those kids, repeating the magic formula against jinni three times is no help at all! And so? Well, nothing—nothing you can do.

~

The ten balls of the foosball table are the first victims to suffer martyrdom. The defenders of the people love Pepsi and Mirinda, its pretty girlfriend. But all they get are the bones, tripe, and hooves of the animals—not the nice red meat. That is sent to the other shore and the countries of the Gulf. Every day we hear that Coke wears your guts away faster than Pepsi and Coke comes from Altanda or Adlanta, in short from the city of the racists who assassinated the good priest Martin Luther King and tried to put an end to the days of James Brown, the king of gospel our young people worship and raise to the very top of heaven.

Our street performers, who are paid by the Coca-Cola dealer, loudly praise the Coca-Cola Company all over the place. They really whoop it up, waiting for the Arab boss to throw them their little weekly coin. They vow to hang the other guys high. They treat us as if we were a contagious disease.

~

Under the burning noonday sun, people rush to the local dives to cool off with the drink of their side, or of their rank. And get this: there was almost a stampede when a new shopkeeper on the square tried to introduce a new brand of cigarettes to dethrone the eternal Craven A’s, Rothmans King Size, or Benson & Hedges: the importer is that same Arab distributor. His venture turned out badly and his goods were auctioned off in the middle of the night. They say he’s sadder than a stone and no one can bring him to his senses. He shouldn’t have gone up against someone stronger than he is.

All around the square, the city looks up and examines the grim horizon. Nothing really new to chew on. No boats in the port wrapped in fog. No prey caught on the high seas, no piece of good news to caress the ears of the town. At the merest nod of a head, the killing will resume between the militias, the clans, and their pirates. Luck will wink at a few people once again. Juicy deals, the vertigo of profits, the takeover of businesses abandoned by the Indians and Arabs for the benefit of the true nomad sons whose umbilical cord is buried back in the neighborhood where they were born. Only they will have the right to do business legally in the wake of the big Arab merchant. The men of straw must be unmasked, like the front men with a taste for foreign brands: Coke, Peugeot, Mitsubishi, Seiko, Orangina, Vache Qui Rit, and all that stuff. What’s left for us to do? Make a mint out of our pox-ridden flesh? Brandish a Kalashnikov and poach every skirt that goes by in the street? Party together?

~

Sitting on the veranda, we watch the rain fall in the courtyard and sense the earth giving out its smell of a pregnant woman. Time falls drop by drop. A few sheep huddle in the least humid corner of the square, now deserted. In the nearby alleyways, you can hear steps sinking into the mud. The wedding of water and crumbly earth. The earth seems to be softly crying under the steps of men.

And now a piece of good news does reach our ears. They say Keynaan Warsame, a true nomad son who left for Canada a long time ago, composes rap songs under his real name, shortened to K’NAAN. One of his songs is supposed to have been adopted as the anthem of the World Cup that’s going to take place in the country of Mandela. We quickly baptize the motionless center forward of our foosball table—the player in the middle of the first row—K’NAAN, hoping that he, too, will not give in to the siren call of Coca-Cola. We listen to the latest rumors in front of the Mashallah grocery. I’m going back to the crowd. Hey, it looks like the game has started.

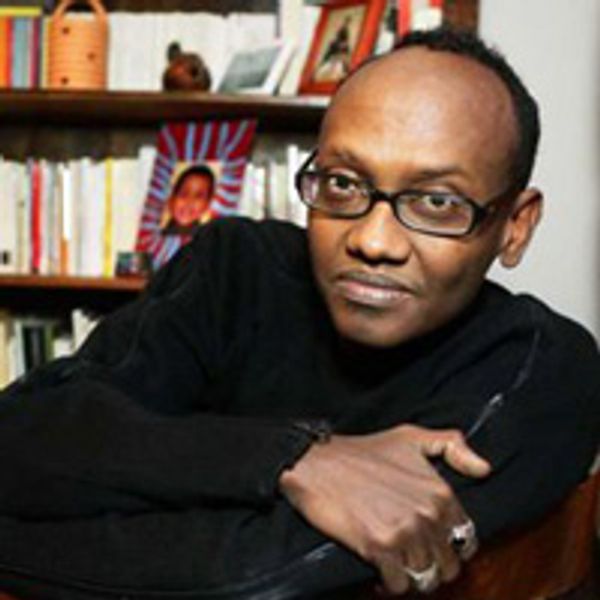

Abdourahman A. Waberi

Abdourahman A. Waberi was born in Djibouti in 1965 and has lived in France since 1985. He has published numerous books, articles, and stories. J. M. G. Le Clézio recognized and paid tribute to Waberi in his 2008 Nobel Prize in Literature lecture. Waberi is currently teaching African literature and postcolonial theory at the Claremont Colleges in California. (updated 10/2010)

David Ball

David Ball’s latest translation is Léon Werth, Deposition 1940–1944: A Secret Diary of Life in Vichy France, which Ball also edited (Oxford University Press, 2018). His translation of Jean Guéhenno, Diary of the Dark Years: 1940–1944 (OUP, 2014), won the French-American Foundation’s translation prize in nonfiction, and his Darkness Moves: An Henri Michaux Anthology 1927–1984 (University of California Press, 1997) won the Modern Language Association’s prize for outstanding literary translation. Coma Crossing: The Collected Poems of Roger Gilbert-Lecomte is forthcoming, as is Marco Koskas’s novel Bande de Français, about a bunch of young French friends in Tel Aviv, from AmazonCrossing. Ball’s own poetry has appeared in half a dozen chapbooks. He is professor emeritus of French and comparative literature at Smith College. (updated 6/2019)

Nicole Ball

Nicole Ball and her translating partner (and husband) David Ball have signed two book-length translations together, most recently Abdourahman A. Waberi’s In the United States of Africa (University of Nebraska Press, 2009). They have also co-translated half a dozen shorter pieces by Waberi for journals such a Words Without Borders, The Literary Review, AGNI, and Calaloo. Nicole has translated two books from French to English—Maryse Condé’s Land of Many Colors (University of Nebraska Press, 1999) and Catherine Clément’s The Weary Sons of Freud (Verso, 1987)—and a Jonathan Kellerman thriller from English to French: La Sourde (Seuil, 1999.) (updated 8/2010)