Lia Purpura, Decaying Wood (detail), featured in AGNI 102

When I first approached AGNI with the idea for this folio, I simply wanted to celebrate the 130th birthday of the X-ray, as one might, by writing a little ode to its wonders and inviting several writers to join me. Like most of my favorite inventions, this form of electromagnetic radiation was discovered by accident, by Wilhelm Röntgen in 1895, who completely changed science (and science fiction) forever. The X-ray enters our lives when we are young, even if we don’t know exactly what it is, and captures our imaginations . . .

—from Rosebud Ben-Oni’s introductory essay

- Rosebud Ben-Oni - Introduction

- Diego Báez

- Michael Brockley

- Diana Cao

Rosebud Ben-Oni

Halo Darkness, My Old Friend

In the dim examination room, I’m staring at very fine but visible print on a mammogram reading. Architectural Distortion. No Sonographic Correlate. Suspicious for Malignancy. Radiant, twisted whiskers are pulling something “down” (or rather toward) an area in my chest that has no visible mass. They do not know why. BI-RADS 4: Biopsy recommended. The radiologist is speaking to me, and has paused. I believe I’m supposed to answer. Believe. Ah, that tricky word so mistrusted by science. I was in trouble from the get-go. Once I referred to HaShem as The Most Impish Engineer. This greatly displeased my AP physics teacher in high school. Horrified the chief rabbi in my shul. Poetry is my shul, I’d told the junior rabbi, who was so much easier to talk to. My childhood and teenage years were alternating periods of upheaval and turbulence. No seatbelt to fasten, rarely a safe landing. So much, I believed, was obscured from my view. The junior rabbi, Rabbi B., would listen to my nascent thoughts on a theory I would develop later, one that swings imperfectly, uncomfortably, between faith and science, Jewish mysticism and theoretical physics: that two natural forces control all natural law: creation and nullification. God and what I’d later call Efes, Hebrew for zero, but in less traditional thought, nullification and also concealment. I had the feeling, the belief, but not the clarity of sight. I certainly didn’t yet have the language, although my parents tried their best to understand me. As a mixed Jew with strange ideas that didn’t make me popular as a teenager, my sense of belonging was highly fractured; it would be years before I understood that my Judaism was chiefly between HaShem and myself, and discovered the “music” that would slowly unconceal, bit by bit, what I so sorely wanted to see and am still trying to name. After one particularly bad day of isolation at Hebrew school, Rabbi B. took me into the main sanctuary at our temple. I could not stop crying. Things had happened to me as a child that should never happen to anyone, and I went through periods of believing I’d buried them so deeply no one could see. By “them” I mean the radiant, twisted whiskers that shone in certain lights, sometimes radioactive—memories that seemed like they belonged to a little girl who’d died. I never mourned that girl. I still don’t know how to. I carried these things inside, hoping the light, the combination of real light and the light of my belief, would keep them hidden. I never told Rabbi B. I never told anyone, until the pandemic came along, and while I was sheltering in place in a dangerous situation, it all poured out. That was later. In the synagogue, Rabbi B. took me up to the bimaand opened the main ark. In the dim, early-evening light filtered through stain glass, he took out a Torah scroll, with its silver crowns, shimmering bells, and elaborate breastplate, its dark, velvety mantle protecting the parchment. Tears were still running down my face. He did not ask me to wipe them. I pressed one side of my face to the soft mantle, and Rabbi B. asked if I could see that God was with me, that he would not, would never desert me. I don’t remember whether I answered. We stood like that for what seemed forever, until my hand somehow slipped past the mantle and touched the Torah itself. One is not supposed to do that. When you read from the Torah, you use a yad, or pointer, to keep track of the text. I don’t remember if Rabbi B. saw. It was just a moment, but as I pulled away, tiny electrical impulses radiated through my hand. I’d crossed a line, though I meant no harm. My guilt and sorrow were instant. But so was a connection. An awakened determination. I don’t remember me letting go or Rabbi B., returning the Torah to its place or both of us leaving the dark sanctuary. What I do remember is a troubling feelingthat I would come to bet on: that life—at least, my life—was meant to be hard so that evolution would take place. That if I were to get close to answers, the questions themselves would change. And I’d be tested over and over. Would waver, doubt, fail. And here I am. Here I am, having failed the screening mammogram—

You didn’t “fail” the mammogram, Ms. Ben-Oni. Take your time. Catch your breath.

~

We are still in the examination room. I am still in the purple gown. A kind nurse has brought me water. I gulp it down. New York City has been very hot this summer. I am used to subtropical humidity, and now I’m shivering in this cold dry room. I start over. Yes, I did not fail the screening mammogram. Rather, I got called back for a diagnostic mammogram. Now they tell me I am BI-RADS 4. (Bi-Rads. Sounds like an ’80s band made up for a rockumentary). The BI-RADS categorizes findings and assigns a range. The range of BI-RADS 4, if you’ll pardon my frankness, is bullshit: 2 - 94% chance of malignancy. But the real kicker is that my Architectural Distortion appeared only on the mammogram and not the sonogram, which isn’t not unusual, but also can be not unusual, and what’s more: there’s no mass where my Architectural Distortion is. So something is pulling something, but they don’t know what. And they won’t know until there’s a biopsy. So . . .

Ms. Ben-Oni?

I was saying, The results sound about right.

Sound what?

I mean it all sounds terribly impish.

Impish.

My world, Doc. I’m always saying that as soon as we get close to solving a riddle the question changes. It’s another test—I’m sorry, a follow-up.Look, Doc, I can’t fail.

Like I said before, you didn’t fail.

Let’s hope not.

Why do you think the question changes?

So we evolve. To get closer to seeing, to unconcealing, another layer of the unknown.

Then think of the biopsy like that. What we can’t see on the mammogram will show itself in the biopsy.

Way ahead of you, Doc.

~

When I first approached AGNI with the idea for this folio, I simply wanted to celebrate the 130th birthday of the X-ray, as one might, by writing a little ode to its wonders and inviting several writers to join me. Like most of my favorite inventions, this form of electromagnetic radiation was discovered by accident, by Wilhelm Röntgen in 1895, who completely changed science (and science fiction) forever. The X-ray enters our lives when we are young, even if we don’t know exactlywhat it is, and captures our imaginations. Who didn’t wish they had Superman’s X-ray vision, only to stare at an X-ray of their leg after attempting superhero stunts? When we grow up, we learn that X-rays use ionizing radiation, and served as a gateway to larger, more complicated nuclear reactions—which can mutate DNA, and decimate cities. I think it’s no coincidence that Peter Parker was bitten by a radioactive spider and his own uncle uttered: With great power comes great responsibility.

That quote has shaped (and haunted) my life as a young would-be scientist and now as a poet and writer, during which so much that was once science fiction has become very real. This is the trajectory humankind has decided to bet its fate on. I think back to the first X-ray ever taken, of Röntgen’s wife’s hand. Her response: I have seen my death.

My radiologist does not care for this quote. She also didn’t know it was the X-ray’s 130th birthday, though it didn’t surprise her that I knew and had already prepared something. This piece, like my recent blog post for AGNI, has taken an unexpected turn. Perhaps a wrong turn, but one I can say is my own. Sometimes our hands slip under holy mantles as a way of resisting death, as a way of saying, I am alive and wish to remain so, as their own form of self-determined connection to the unknown. Just the way that hands and knife can slip in, through biopsy, and unconceal what a mammogram could not. With a week to go before my biopsy, I slide between fear and fortitude, taking long walks in my beloved Queens, New York, unable to talk to anyone about anything. It’s just the city and me, the 7 train roaring above me on its elevated tracks. The days are long and hot, and on some I walk all the way to Last stop, Flushing. I try to keep to my deadlines, my responsibilities. My life has been turbulent always, but now at least I have better language to carry me. I’m feeling impish again. And in the grand scan of our collected lives, see how far humans have come since the birth of the X-ray? See how, when fear takes over and we can’t bring ourselves to look, the results wait for us? It’s up to us to decide where to go from there. Myself, I feel a little closer every day to an answer to What if. Not a grand epiphany, but a faint clue that meanders through the darkness. A trace so translucent it seems part of a larger system coming reluctantly into view. Call it electromagnetic, call it miracle. I get so close I see my hand pass under.

I see my own hand become the very mystery eluding me.

And then, poof: the riddle changes. The cycle reconfigures. The question distorts its own architecture.

All the things we’ve bet on have taken on new, unknown forms.

All the cards we hold turn into relics.

And I say: What if?

What if indeed.

Bring it on.

And I say: Next.

Diego Báez

To See Inside for Oneself

In 1994, when I was ten, I broke my foot playing basketball in our backyard in Bloomington, Illinois, and when I say playing, I mean HORSE on the cramped concrete patio behind my childhood home, by myself. I didn’t have anyone to play with in those days, but I spent entire afternoons nailing trick shots against famous players. At the time, I idolized big men, power forwards and centers: Shawn Kemp, Dennis Rodman, Shaquille O’Neal. Dial-up internet had not yet crowded our landline, so shining images of my favorite players would arrive on television or in print: NBA Inside Stuff, SLAM, Sports Illustrated.

(Later, The Pantagraph, our small-town newspaper, ran a front-page photograph of Michael Jordan beneath his iconic two-word press release, “I’M BACK.”)

On Saturdays, I sold trading cards at a strip-mall flea market on the other side of town. I can still smell the old cardboard and trace the mighty dust motes drifting in the afternoon light, holographic foil splashing rainbows on my face as I perused, lips pursed in deliberation. Papi stood next to me, chilling, a copy of Beckett magazine rolled in his hand, indifferent as to whether I’d made a good deal or gotten ripped off. I often think about his silence on these questions of money.

(Years later, I enrolled in Econ 101 at my father’s urging. I wasn’t ready for the course—by which I mean, I didn’t care. In fact, my fondest memories of that college are from much earlier, around the time of my broken foot, when I tagged along with my dad to watch the men’s basketball team win their way to a Division III championship.)

I used to pray to God to make me seven feet tall. Maybe then I’d achieve my dream of playing with other boys or men, streaking across actual hardwood in a blur of muscle and sweat, instead of alone in the humid Illinois twilight, by the light of the neighbors’ kitchens’ incandescing.

(I did end up playing for St. Mary’s Catholic Church in eighth grade. The royal blue and faded gold of our mis-sized uniforms flashed hustle and amateur. I doubt we won a single game. The only Latinos I ever called friends played on that time—point guard and shooting guard—but after our Confirmation, I never heard from them again.)

From beneath that basketball hoop in my backyard at dusk, I’d witness the slow exposure of each family’s private lives, their nighttime rituals and movements, how each conducted itself in concert against the waning of the day.

(Many years later, newly employed as a full-time faculty member at Truman College in Chicago, I was touring a storage space in the basement when an oblong desk slipped from a stack and pinned my foot to the floor by the metatarsal. This was two weeks before my wedding, and I could instantly see my future cast and crutches, my sad limp down the aisle, my bride terribly embarrassed by it all.)

Back in Bloomington, dark figures of fathers and mothers, brothers and sisters, configured themselves into shapes recognizable as grace before dinner, cleanup and chores, bedtime, TV. That summer of 1994, I ended up getting a boot for my foot. I enjoyed watching the neighbors’ domestic pantomimes as I healed, but that thing itched like hell. I couldn’t wait to remove it, to witness the resurrection of the flesh. To get rid of the plaster and know my foot cured. To finally see inside for myself.

Michael Brockley

Three Segments

A Fluoroscope in Connersville

Our mother warned us against using the fluoroscope in Merit’s Shoe Store. She’d read an article in Life that stirred an urge to protect her children from radiation. Jack took her caution to heart. I, though, tried on a pair of penny loafers and put my feet on the X-ray plate. What did I know about science? The contraption looked like a prototype for a time machine. The kind of futuristic device that piqued my curiosity in comic books or Saturday afternoon matinees. It had three View-Master attachments: one for parents, one for salesclerks, and one for reckless children. I restrained myself from twisting the black knob or pressing the white light. I never figured out the purpose of the vaguely rectangular siren-like contraption.

On the screen, I could see my right pinky toe curled over on itself, like a pill bug exposed to sunlight. Earlier salesmen overlooked the defect, preferring a Brannock device and a shoehorn to “science’s perfect shoe fit.” I wiggled my toes to check for comfort, imagining myself dancing on St. Gabriel’s gym floor, wondering if the nuns would banish me.

I hankered for a superpower that would let me read hearts and minds. Looked forward to being bitten by a black widow spider while modeling a pair of brown Florsheims under the fluoroscope. Anticipating my silhouette crouched on the shoe store’s roof, my hometown’s first sentinel.

X-Ray Visions

A plastic ankylosaur from the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. A tangle of magnets. Bobby pins and earrings and Mercury dimes. A golden Sacagawea dollar. Absolution for Ay and Horemheb, suspects in the death of Tutankhamen. An unexploded grenade in the chest of a Ukrainian soldier. Pink school erasers, mandalas, and stars for charm bracelets. Screws, spoons, and skeleton keys. Forks with bent tines. Carved ivory turtles and onyx cranes. Chopsticks. Miniature Pontiac Grand Ams with fire emblems on their rear side panels. Candy canes. Lego pieces for the Mos Eisley Cantina™. A teratoma with teeth, bone, hair, and muscle, and a kidney stone that resembled an ostrich egg. The specter of Anna Bertha Ludwig’s left hand. Four opened safety pins lodged in a baby’s esophagus, fed to the child by his siblings.

The Skiagraphy Grand Opening: A Flyover Gothica Tour

The King of Rock ’n’ Roll greets us with swivel hips at the entrance to The Museum of X-Ray Art. His suit, woven from wisps, covers the gyrating bones. His feet prepare to leap or spin while he grabs the white mic for his walk down lonely street. Around us, hidden speakers play the bone music that Soviet Russians bought on the black market: 78 RPM platters made from discarded X-rays, a hole burned in the center with a cigarette. We are the sons and daughters of housewives, store-display craftsmen, Christmas-tree farmers, waitresses, fourth-grade teachers, and postal clerks. Above us, “It Happened in Autumn” and “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” serenade our tour. The songs skip in the shallow grooves. We linger before a woman’s foot distorted by a stiletto heel. Converse about the X-ray choices a chameleon might make, how it would shape all the grays to its advantage. We debate whether flowers in black-and-white negative look more like mushrooms or les fleurs du mal. When we reach a still of one of the artists, he removes a mask and leans in to operate a movie camera. He’s turned his skull to shake the ash from his cigar, and toasts us with a tumbler of blue bourbon.

Diana Cao

Now That We See

Last week, while I was on a video call with my friend Nadia, a lightning storm ripped through the backyard of my parents’ house. I turned out the lights so Nadia and I could watch the drama unfold, my room flashing in and out of existence.

Each time the purple light flooded my half of the screen, it seemed possible that the face there might not be mine. I saw: distorted features, a blurred outline, a skeleton. Each flash showed the promise of the stranger I might become if I could just make it past this year, and then another promise beyond that—the one about the moment we won’t survive, the material limit to our time in the world.

Both visions had their appeal: neither of them was the reality I felt trapped in, having moved to my parents’ home several months earlier to help while my mom was on chemo. I was away from the life I’d built in Cambridge, with friends who made me believe it was possible to live with others and remain kind; with the corner pizzeria, whose owner had seen me through the beginnings and ends of relationships, the beginning and end of law school, while I watched his son grow up there in the shop; with the city blocks that I had walked at all hours, in all seasons, thinking my life was my own. Now I was back in the place I’d always feared I wouldn’t successfully outrun.

In cartoons, when someone touches a power line or is struck by lightning, their skin turns translucent and their bones light up for as long as the current flows. This trope is called the “X-ray spark,” as a nod to the X-ray specs sold at the back of every comic book for decades. X-ray specs were plastic eyeglasses whose lenses consisted of a feather held between thin sheets of cardboard, yielding slightly offset images when you looked through them. They were marketed with the slogan, “See the bones in your hand, see through clothes!”—but as Wikipedia notes, since the wearer couldn’t really see through anything, “Part of the novelty value [lay] in provoking the object of the wearer’s attention.”

But that person, the object, must have known that cardboard glasses couldn’t compromise their modesty. So were people just squeamish under scrutiny? Or was it the suggestion that the wearer wouldn’t hesitate to breach that contract, to look inside them or see them naked, if only the technology were available?

~

When Wilhelm Röntgen made the first X-ray image of his wife Anna Bertha’s hand—wedding band darkening her finger above the tapering joint—she declared, “I have seen my death!” In the year that followed, at least forty-nine essays and 1,044 articles about X-rays were published, including some linking them to paranormal and occult phenomena, like telepathy.

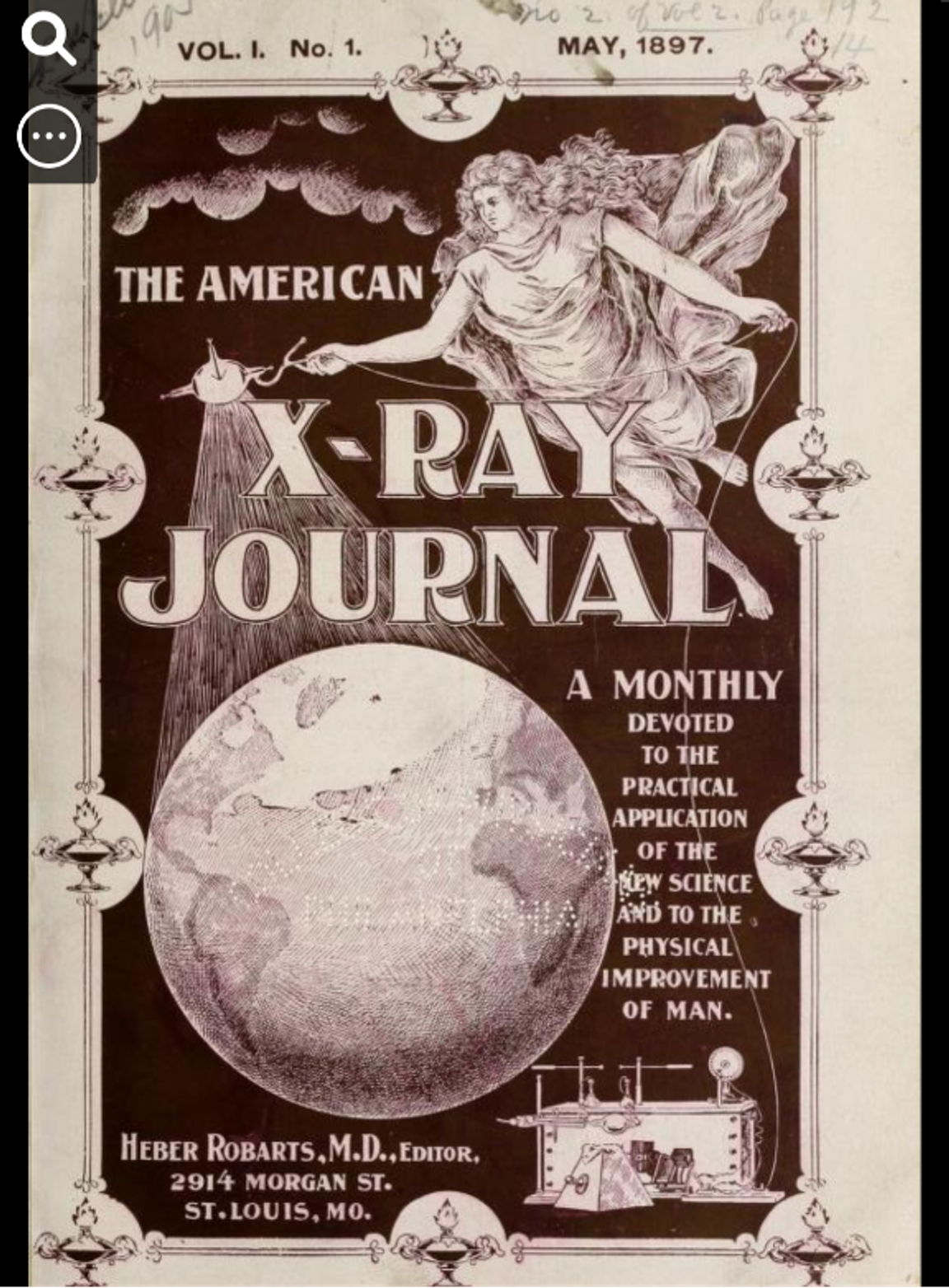

In 1897, The American X-Ray Journal—devoted to “the practical application of the new science and to the physical improvement of man”—released its first issue. Even in that “practical” journal, Homer C. Bennett, M.D., M.E., published a poem fantasizing about the possibility that the new rays could show the lump in our throats during an emotional proposal, or our heart in our boots when we were afraid. He called it “What We Want to Know.”

The technology’s promise went beyond its ability to diagnose fractures. In making what had been invisible visible, it suggested we could gain clarity about our feelings, our temperaments, and our futures.

Of course, anyone who’s been to therapy long enough knows that self-understanding doesn’t necessarily lead to enlightenment. And even with something as tangible as a broken bone or a nodule in a lung, visibility doesn’t always suggest a cure. The hard part is still to come.

~

When my mom was diagnosed with lymphoma earlier this year, it was in some ways a relief to have something we could see on a scan. She’d been losing her memory for more than a decade, asking me the same questions over and over: What was I doing in Boston? Did I think it was going to rain? What made clouds look like that? She forgot our home address once or twice, then once or twice a week; she insisted to strangers that she knew them, grabbing them by the arm with a force of personality (and a lack of boundaries) that hasn’t changed.

Every time I came back home, it seemed her memory had worsened. Each time, I thought: Maybe this is it. My grandmother, her mother, had begun to lose her memory in her sixties—and she’d lived for another thirty years, needing constant care for most of that time. So I’ve been running back and forth between preparations for the kind of life that might factor in care and all its contingencies, on one hand, and screaming resentment and refusal of those responsibilities, on the other. Mostly, I’ve kicked any permanent decisions down the line.

It turns out I wasn’t prepared to understand how much more difficult her care would become, and how quickly, when she stopped remembering anyone in her contact list and became an ideal target for every scam, when she woke up in the middle of the night asking for my dead grandmother, when she insisted we hadn’t gone out, not five minutes after stepping back in the house, when she forgot she’d already eaten and kept eating until she made herself sick.

Cancer brought a further explosion of uncertainty. How would my mom respond to treatment? How was I going to explain to her, with her memory loss and the language barrier between her and her doctors, what was going on?And when, if ever, would I be able to return to my own life? What did I owe to the flawed people who’d traversed their own hells to raise me?

If only I had X-ray specs for that.

But the tangibility of the diagnosis, its visibility on X-ray film, did change things. There was no longer the luxury of wondering what might be happening inside my mother. Now that we’d seen what we’d seen, the questions became clear: What are we prepared to do about it? And what can we?

~

Anna Bertha hadn’t been wrong when she said she saw death in the X-ray image of her hand.

Long exposures were needed to produce those early pictures. Subjects would sit for over an hour while radiation burned through them. Patients lost hair and skin; doctors and manufacturers lost limbs and sometimes their lives.

But the death was symbolic, too: death of the world they’d known, where our insides remained hidden from sight. Now, suddenly, anyone could stare at the crack in the bone. The unknown mass. On the other hand, total knowledge—total mastery—of the self seemed within reach.

This year, over a century after the X-ray’s discovery, many of our lives are shaped around that fantasy. We offer ourselves up to fitness trackers, search engines, doorbell cameras, and end-of-the-year recaps. We allow technologies to reflect ourselves back to us, forgetting our old unease around X-ray specs—the power inherent in being the watcher, and the powerlessness of being the one exposed but not really seen.

It’s important to remember those power dynamics now. In the last years, we’ve watched as people like us have streamed their own deaths and displacements, auditioning for empathy from a world that fails to do anything about it. We see videos of children and adults starving—being starved—in Gaza, and then we, what? The trap of the X-ray, the trap of visibility, is that it can make us think that looking is itself the decisive act.

~

My mom’s oncologist sees cancerous activity on the PET scan and needs to consult with the tumor board about radiation therapy. I see a fuzzy shape of the years of care to come, and don’t know exactly how we’ll get through it, or what shape my regret or love might take. I don’t know if love will have anything to do with it.

All I know is to say: take a look at this moment, illuminated in the flash. I’m writing in July 2025, during a summer of genocide, mass starvation, unusual thunderstorms, ICE raids, friends getting pregnant, care packages, my mom’s chemo, and new books, not to mention invasive lanternflies, strawberry matcha, Zohran Mamdani, AI, sculpture museums, heat domes, love poems, and anticipatory grief.

It’s just a moment, soon to be gone. Like an X-ray, what we see is a snapshot in time, even if it isn’t as clear as the break of a bone or a tumor awaiting excision. The way forward may be cloaked in uncertainty, but the next moment depends on what we do after seeing what we’ve seen. I’m trying to remember this as I write with rain coming down again on my parents’ roof. Another flash of lightning.

agnimag

By the AGNI staff.