Malak Mattar, My Mother (detail), 2021, oil on canvas

After the Earthquake: Poets for Haiti

Poets for Haiti: An Anthology of Poetry and Art, selected and introduced by Kim Triedman. 68 pgs. Yileen Press, 2010.

This slender but varied collection grew out of a moving event hosted by Harvard University in February 2010: a poetry reading to raise funds for the earthquake victims in Haiti. As described by Kim Triedman in her introduction, the benefit was held just six weeks after the capital city of Port-au-Prince and smaller towns such as Jacmel were devastated by the worst natural disaster in Caribbean history. All proceeds from the sale of the volume—illustrated by eight gifted artists, including Pascal Monnin, Paul Gardère, and Edouard Duval-Carrié, to name a few—will go to assist the work of the Boston-based nonprofit Partners in Health, which already has to its credit twenty years of experience in Haiti. The brief preface by two representatives of the charity, Paul Farmer and Ophelia Dahl—written as the book was going to press, six months after the catastrophe—outlines the progress made in the relief effort, and issues a further plea for donations.

Given the laudable intentions behind this book, it would be impossible to review it as just another anthology—in fact, the word “anthology” seems irrelevant here in its usual sense, since it implies a culling of pieces based on a certain set of aesthetic, historic, or cultural criteria. From the outset, the poets who took part in the original reading shared only one thing, beyond poetry itself: their desire to take a public stand in support of the ravaged nation. This was a humanitarian as opposed to a literary impulse, uniting poets of a wide diversity of technical prowess and thematic scope. They range from a high school student to a former Poet Laureate, and from populist writers to academic literati. Elitism plays no part in this selection, though the poems all merit close attention throughout; I, for one, found the quirky democracy of the voices here boldly refreshing. The heterogeneity of Poets for Haiti converts it into something rare and valuable: a book which transcends poetic schools or political ideologies. Instead of a repetitive chain of elegies, a strident phalanx of “poèmes engagés,” or an artful sampler of “anthology pieces,” the book affords an unbiased view of the eclectic vigor of contemporary letters.

The title of the collection tips the reader off that many of the poets featured here are not Haitians themselves. Judging from the lively biographical sketches assembled by Kim Triedman, fewer than half can claim some kind of native or ancestral connection with the country, and even most of those now live in New England. More surprisingly, only eight or nine of the thirty poems in the anthology bear any direct relation to Haiti. Patrick Sylvain’s “Boulevard Jean Jacques Dessalines” grants us the most vivid glimpse of everyday life on the island, with its noisy markets and bubbling verve:

Dessalines Boulevard

Is a chaotic heap where hips violently sway

To navigate busied feet that rid of goods so children

Will not go hungry. I zoomed in on frenzied hands,

Grabbing worn foreign goods. I panned and framed

Pouting lips, a desperate buyer noticed my invading lens.

Just a handful of poems actually address the earthquake itself—perfectly understandable, given its recentness at the time of the Harvard reading. Among them, “Intersection” by Danielle Legros-George, Tom Daley’s “After a Stroke, My Mother Addresses Children in a Photograph of a Sidewalk in Port-au-Prince,” and “Earthquake” by Marilène Phipps-Kettlewell deserve a special mention, as the most innovative in their imagery and emotional thrust. In “Earthquake,” we read of the collapse of bodies and buildings, and see vividly the destruction wrought in Port-au-Prince:

The roofs of all of Port-au-Prince collapsed.

They collapsed onto the people they sheltered.

They buckled, contorted, cracked, sagged, crumpled, slumped and

caved in. Limbs of Churches lie with limbs of people,

dried, splintered, brittle and oddly disassembled

like limbs of a crustacean carelessly crushed

under a murderous foot.

Humans severed and suffocated lie

among broken statues—martyrs

and angels without wings.

The sun pulls moisture from souls trapped

alive; a hard white dust covers the city.

In her poem “After,” Rosanna Warren tacitly draws a connection between the Haitian cataclysm and the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans. This comparison seems all the more appropriate given the African origins of most of those who suffered in both instances. From there, Robert Pinsky takes a further step: in his reliably virtuoso piece “Ginza Samba,” he celebrates the vibrancy of the African diaspora as a whole, without alluding to either tragedy. On behalf of all of the downtrodden, not only those of African descent, Fred Marchant’s “A Place at the Table” and Togiram’s “I’m Writing a Poem” demand equality and justice for those who have not profited from globalization or economic expansion: the poor in both North and South, the developed and the so-called “developing” world. If natural disasters come and go, the cruel dilemma of the dispossessed remains, the authors imply; a one-time response to a specific appeal will never be enough to change their fundamental misery, which calls for a radical transformation from bottom to top.

Most of the remaining selections—some by such noted poets as Daniel Tobin and Gail Mazur—make no pretense of a topical link to the Haitian earthquake, nor do they need one. The presence of all these authors at the original benefit gives strong support to the idea that poetry itself induces its practitioners and adherents to a spontaneous empathy for others: sensibility and sensitivity spring from the same root, empirically as well as etymologically. In that light, there would be no point in asking the grander question: Can poetry serve a cause? Or more modestly: Can a poetry reading give coherent shape to an anthology? All the poems included in this collection are satisfying in their own right, and the book is eminently worth buying for that reason alone. But by acquiring it, the purchaser can also aid the people of Haiti even today, and participate in the movement of solidarity which gave rise to this urgent assemblage in the first place. Poets for Haiti wears the insignia of openness and generosity, both poetic and humane.

Hoyt Rogers lives in the Dominican Republic. His poems, stories, and essays, as well as his translations from the French, German, and Spanish, have appeared in a wide variety of books and periodicals. His most recent book is, as translator, Yves Bonnefoy’s Second Simplicity: New Poems and Prose, 1991–2001, parts of which first appeared in AGNI. (8/2011)

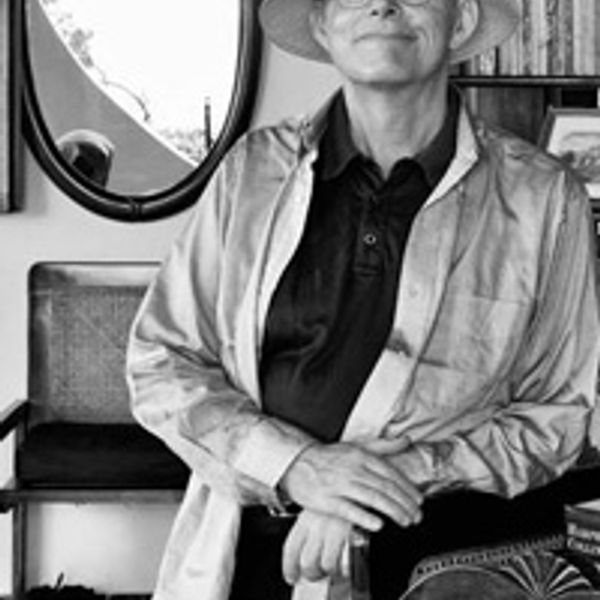

Hoyt Rogers

Hoyt Rogers’s forthcoming works include Sailing to Noon, the first novel in The Caribbean Trilogy (with Artemisia Vento). He is the author of the poetry collection Witnesses and book of criticism The Poetics of Inconstancy. His poems, stories, and essays have appeared in New England Review, The Antioch Review, AGNI, The Fortnightly Review, and dozens of other publications. Rogers also translates from French, German, Italian, and Spanish. He has translated four books by Yves Bonnefoy, most recently Rome, 1630 (Seagull Books, 2020), which won the French American Foundation’s Translation Prize. He translated and edited, with Paul Auster, an anthology of poems and journal entries by André du Bouchet, Openwork (Yale University Press, 2013); and with Eric Fishman, he translated du Bouchet’s Outside (Bitter Oleander Press, 2020). (updated 10/2021)