Lia Purpura, Parasol Mushroom (detail), featured in AGNI 102

Learned Libraries

Translated from the French by Hoyt Rogers

The library of the French School in Rome . . . Here I am, a young man doing research on the Mirabilia Urbis Romae, a project entrusted to me by André Chastel. And I have just made a discovery: one of those old guidebooks on a shelf, unknown to me a moment before and probably to anyone, since it’s not a printed work or a manuscript, but a cup, filled with water to the brim. I pick it up with all the caution of a scribe, a philologist, and carry it to my table—which I enjoy finding free on these sultry mornings, because the window to my left overlooks the belfry of La Sapienza.

Here is the cup. I have set it down between my notebooks and my books, without spilling a drop. I examine it. Is this really water? Its coolness permeates my fingers; and what is more, it gives off reflections, which seem to disregard today’s bright sun. Reflections, or rather images of some kind. They rise to the surface of the world and unfurl all around me, a little blurred at first and then more distinct. Where am I? Whose hands are these I see begin to move, right before my eyes? What worries make them fidget? What are they looking for, on this table stacked with things? There is a pocket-knife I vaguely recognize; some books I think I read long ago; a notebook in a familiar hand, though I can’t quite place it. Am I the one taking up this pen? And who in this other world has prepared me to write, yet hesitates? Who am I in fact?

But then it dawns on me: I know what chapel this is. It dates from the first Christian centuries, and its vaults enclose the monodic voice of incense. In the shadows of the side aisles, I am working here at present. At the Clark Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, this is the underground library—among the few absolute places that exist on earth. And I am seated at one of the vast tables, perusing a recent book about Goya’s black paintings. Now I am old. As it turned out, I never wrote my thesis on the Mirabilia. Nor did I often step away from some grassy street, with the evening sun at its far end, to slip into one of those small churches of Rome—the mosaics on their walls faintly glimmering, like gold within a dream. What am I doing here in the Berkshires, so late in my life? Why did I come? But of course: no doubt I am taking up again my other great project of bygone years, a study of forms and their meaning in Piero della Francesca. I used to wander with that young painter, laughing and conversing, on the gentle hills of clear Umbrian mornings. Am I going to apply myself from now on? But these are not jottings, or drafts of chapters, which my nervous hands leaf through. All they uncover beneath the notebooks and the books is a tiny mirror, beaming with light, a fire from the open sky. This astounds me, since I am two floors below ground—or so I believe.

But why should I be amazed? The mirror, its water sweet and serene, is simply the university library of Coimbra—where this time, night has also fallen. Its beautiful sculpted shelves are barely visible in the faint light of low lamps. The central aisle retreats into darkness. The famous bats of this abode of poetry and learning dart silently, along a ceiling I cannot see. And there is no one seated at the tables, no one but Goya: as at the outset of the Caprices, racked by bad dreams, he buries his forehead in folded arms. I stand up and sidle by him. I walk toward the end of the great room—going where, I do not know.

Yves Bonnefoy, often acclaimed as France’s greatest living poet, has published ten major collections of poetry in prose and verse, several books of tales, and numerous studies of literature and art. He succeeded Roland Barthes in the Chair of Comparative Poetics at the Collège de France. His work has been translated into scores of languages, and he is a celebrated translator of Shakespeare, Yeats, Keats, and Leopardi. Most recently, he has added to his long list of honors the European Prize for Poetry (2006) and the Kafka Prize (2007). He lives in Paris. (11/2012)

Hoyt Rogers has published over a dozen books, including his own works as well as translations from the French, German, and Spanish. His versions of Borges appeared in the Viking Centenary Edition. His most recent translation from the French, Second Simplicity—verse and prose by Yves Bonnefoy—was published by Yale University Press this year. With Paul Auster, he is currently translating Openwork, an anthology of poems by André du Bouchet. He divides his time between the Dominican Republic and Italy. (11/2012)

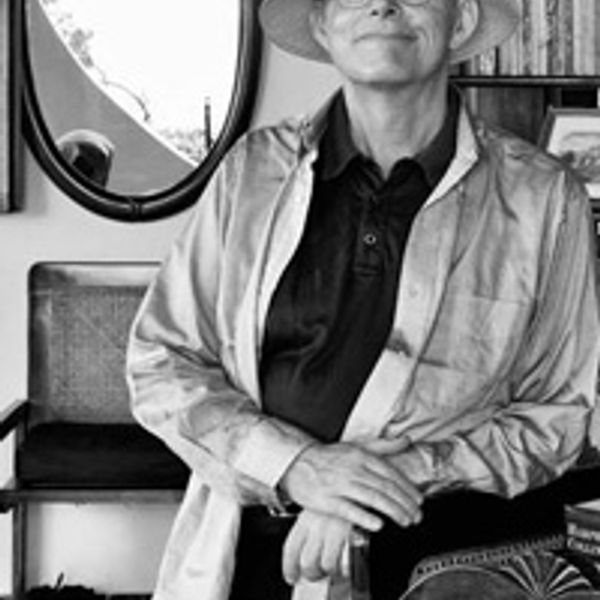

Yves Bonnefoy

Yves Bonnefoy (1923–2016) is often acclaimed as one of France’s greatest poets. He published ten major collections of verse, several books of tales, and numerous studies of literature and art, and was a celebrated translator of Shakespeare, Yeats, Keats, and Leopardi. His work has been translated into scores of languages, and he earned many honors, including the European Prize for Poetry (2006) and the Kafka Prize (2007). He succeeded Roland Barthes in the Chair of Comparative Poetics at the Collège de France.

Hoyt Rogers

Hoyt Rogers’s forthcoming works include Sailing to Noon, the first novel in The Caribbean Trilogy (with Artemisia Vento). He is the author of the poetry collection Witnesses and book of criticism The Poetics of Inconstancy. His poems, stories, and essays have appeared in New England Review, The Antioch Review, AGNI, The Fortnightly Review, and dozens of other publications. Rogers also translates from French, German, Italian, and Spanish. He has translated four books by Yves Bonnefoy, most recently Rome, 1630 (Seagull Books, 2020), which won the French American Foundation’s Translation Prize. He translated and edited, with Paul Auster, an anthology of poems and journal entries by André du Bouchet, Openwork (Yale University Press, 2013); and with Eric Fishman, he translated du Bouchet’s Outside (Bitter Oleander Press, 2020). (updated 10/2021)