Lia Purpura, Parasol Mushroom (detail), featured in AGNI 102

Incomplete Knowledge

I am of those whose knowledge will always be

incomplete, who know something about the world

but not a whole lot, who will forever confuse

steeplebush and meadowsweet

but know at least by the shape of the flower

that it is one or the other.

Don’t ask me the difference between

a white pine and a red, or even a Jeffrey,

but I know it’s a pine, not a spruce or tamarack

(a.k.a. hackmatack, but what’s a larch?).

The difference between a sycamore

and a plane tree? It’s beyond me.

I’ve never had a grip on

Japanese painting—the different styles and periods.

I don’t even know that much about Dutch—

Vermeer of course, Rembrandt sure,

but could I distinguish a De Hooch from a Steen?

Do I even know how to pronounce their names?

I know next to nothing about what goes on

under the hood of a car, though I try to hide that fact

in the presence of mechanics. Herakleitus

(am I spelling that right?) said something

about how we hide our ignorance,

but I can’t remember exactly what it was.

Birds, music, fishing, history, it’s appalling

how limited my knowledge is.

I’m not even going to begin to list

all the books I haven’t read.

I’m the antithesis of a Renaissance man,

spread so thin I hardly exist.

I have a friend who knows what seems like

close to everything. Certainly everything in the woods.

He was explaining to me the difference

between steeplebush and meadowsweet

(which I understood at the time but didn’t retain,

as if it were the theory of relativity),

when I looked up and saw a jet whose trail

of fine white cloud kept disappearing, reappearing,

and disappearing again, and I asked why,

and, holding the meadowsweet in one hand

and the steeplebush in the other, he explained it.

And he wasn’t bullshitting, either—he knew.

I’m not sure I even understand what it means

to know that much. Does all that knowledge

add up to some encompassing wisdom,

something beyond the sum of the names

and data, vast and unknowable? Unknowable

at least to me: I will never be like my friend.

I misplace facts as easily as my glasses,

so the world seems blurred for a while—

but then I find them, put them on, and go outside

to greet the ten thousand things (is that a Buddhist

or Taoist expression?), no less amazed

for my not being able to keep them straight.

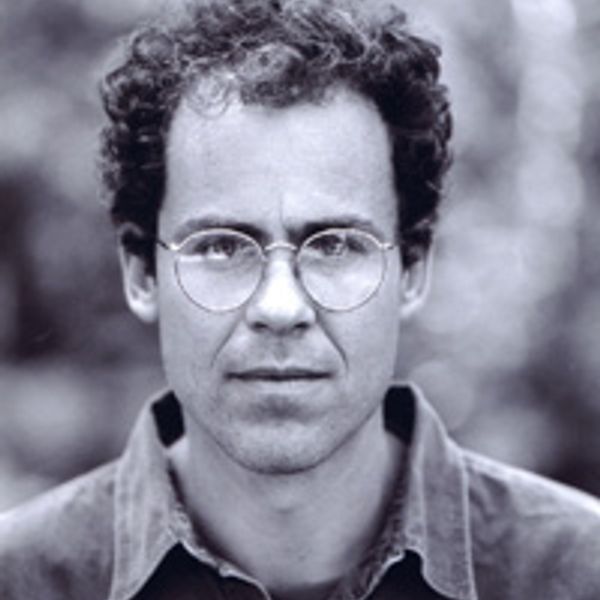

Jeffrey Harrison

Jeffrey Harrison is the author of five full-length books of poetry, most recently Into Daylight (Tupelo Press, 2014), Incomplete Knowledge (Four Way Books, 2006), and The Names of Things: New and Selected Poems (Waywiser Press, 2007). The recipient of fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the NEA, his poems have appeared or are forthcoming in The New Republic, The Kenyon Review, The Hudson Review, Pushcart Prize XXXVIII, The Paris Review, The Yale Review, TriQuarterly, AGNI, The Southern Review, Poetry, Poets of the New Century, and other magazines and anthologies. (updated 10/2014)