Lia Purpura, Parasol Mushroom (detail), featured in AGNI 102

from Omeros, Book III: Achille in Africa, I–III

In this book Achille, a Caribbean fisherman,

is transported to Africa by a sea-swift.

****I

Mangroves, their wrists in water, walked with the canoe.

The swift, racing its browner shadow, screeched, then veered

into a dark inlet. It was the last sound Achille knew

from the other world. He feathered the paddle, steered

away from the groping mangroves whose muddy shelves

slipped warted crocodiles, slitting the pods of their eyes;

then the horned river-horses rolling over themselves

could capsize the keel. It was like the African movies

he had yelped at in childhood. The endless river unreeled

those images that flickered into real mirages:

naked mangroves walking beside him, the knotted logs

wriggling into the water, the wet, yawning boulders

of oven-mouthed hippopotami. A skeletal warrior

stood up straight in the stern and guided his shoulders,

locked his neck in cold iron and altered the oar.

Achille wanted to scream, he wanted the brown water

to harden into a road, but the river widened ahead

and closed behind him. He heard screeching laughter

in a swaying tree, as monkeys swung from the rafter

of their tree-house, and the bared sound rotted the sky

like their teeth. For hours the river gave the same show

for nothing, the canoe’s mouth muttered its lie.

The deepest terror was the mud. The mud with no shadow

like the clear sand. Then the river coiled into a bend.

He saw the first signs of men, tall sapling fishing-stakes,

he came into his own beginning and his end,

for the swiftness of a second is all that memory takes.

Now the strange, inimical river surrenders its stealth

to the sunlight. And a light inside him wakes

skipping centuries, ocean and river and Time itself.

And God said to Achille, ‘Look, I giving you permission

to come home. Is I send the sea-swift as a pilot,

the swift whose wings is the sign of my crucifixion.

And thou shalt have no gods should in case you forgot

my commandments.’ And Achille felt the homesick shame

and pain of his Africa. His heart and his bare head

were bursting as he tried to remember the name

of the river-god and the tree-god in which he steered,

whose hollow body carried him to the settlement ahead.

****II

He was remembering this sunburnt river with its spindly

stakes and the peaked huts platformed above the spindles

where thin, naked figures as he rowed past looked unkindly

or kindly in their silence. The silence an old fence kindles

in a boy’s heart. They walked with his homecoming

canoe past bonfires in a scorched clearing near the edge

of the soft-lipped shallows whose noise hurt his drumming

heart as the pirogue slid its raw, painted wedge

towards the crazed sticks of a vine-fastened pier.

The river was sloughing its old skin like a snake

in unwrinkling sunshine, the sun resumed its empire

over this branch of the Congo; the prow found its stake

in the river and nuzzled it the way that a piglet

finds its favourite dug in the sweet-grunting sow,

and now each cheek ran with its own clear rivulet

of tears, as Achille weeping, fastened the bow

of the dugout, wiped his eyes with one dry palm

and felt a hard hand help him up the shaking pier.

Half of me was with him. One half is in Amsterdam,

by a chuckling canal. But now, neither was happier

or unhappier than the other. An old man put an arm

around Achille, and the crowd, chattering, followed both.

They touched his trousers, his undershirt, their hands

scrabbling the texture, as a kitten does with cloth,

till they stood before an open hut. The sun stands

with expectant silence. The river stops talking

the way silence sometimes suddenly turns off a market.

The wind squatted low in the grass. A man kept walking

steadily towards him, and he knew by that walk it

was himself in his father, the white teeth, the widening hands.

****III

He sought his own features in those of their life-giver,

and saw two worlds mirrored there, the hair was surf

curling round a sea-rock, the forehead a wrinkling river,

as they swirled in the estuary of a bewildered love,

and Time stood between them. The only interpreter

of their lips’ joined babble, the river with the foam,

and the chuckles of water under the sticks of the pier,

where the tribe stood like sticks themselves, reversed

by reflection. Then they walked up to the settlement,

and it seemed, as they chattered, everything was rehearsed

for ages before this. He could predict the intent

of his father’s gestures; he was moving with the dead.

Women paused at their work, then smiled at the warrior

returning from his battle with smoke, from the kingdom

where he had been captured, they cried and were happy.

Then the fishermen sat under a large tree under whose dome

stones sat in a circle. His father said:

‘Afo-la-be.’

touching his own heart.

‘In the place you have come from,

what do they call you?’

Time translates.

Tapping his chest,

the son answers:

‘Achille.’ The tribe rustles, ‘Achille.’

and it runs like a wind in the leaves on the green crest

of a hilltop at sunrise, then all the mutterings settle.

AFOLABE

Achille. What does the name mean? I have forgotten the one

that I gave you. But it was, it seems, many years ago.

What does it mean?

ACHILLE

Well, I too have forgotten.

Everything was forgotten. You also. I do not know.

AFOLABE

A name means something. The qualities desired in a son,

and even a girl-child; so even the shadows who called

you expected one virtue, since every name is a blessing,

since I am remembering the hope I had for you as a child.

Unless the sound means nothing. Then you would be nothing.

Did they think you were nothing in that other kingdom?

ACHILLE

I do not know what the name means. It means something,

maybe. What’s the difference? In the world I come from

we accept the sounds we were given. Men, trees, water.

AFOLABE

And therefore, Achille, if I pointed and I said there

is the name of that man, that tree, and this father,

would every sound be a shadow that crossed your ear,

without the shape of a man, or a tree? What would it be?

(And just as branches sway in the dusk from their fear

of amnesia, of oblivion, the tribe began to grieve.)

ACHILLE

What would it be? I can only tell you what I believe,

or had to believe. It was prediction, and memory,

to bear myself back, to be carried here by a swift,

or the shadow of a swift making its cross on water,

with the same sign I was blessed with, with the gift

of this sound whose meaning I still do not care to know.

AFOLABE

No man loses his shadow except it is in the night,

and even then his shadow is hidden, not lost. At the glow

of sunrise, he stands on his own name in that light.

When he walks down to the river with the other fishermen

his shadow stretches in the morning, and yawns, but you

if you’re content with not knowing what our names mean

then I am not Afolabe, your father, and you look through

my body as the light looks through a leaf. I am not here

or a shadow. And you, nameless son, are only the ghost

of a name. Why did I never miss you until you returned?

Why haven’t I missed you, my son, until you were lost?

Are you the smoke from a fire that never burned?

There was no answer to this as in life. Achille nodded,

the tears glazing his eyes, where the past was reflected

as well as the future. The white foam lowered its head.

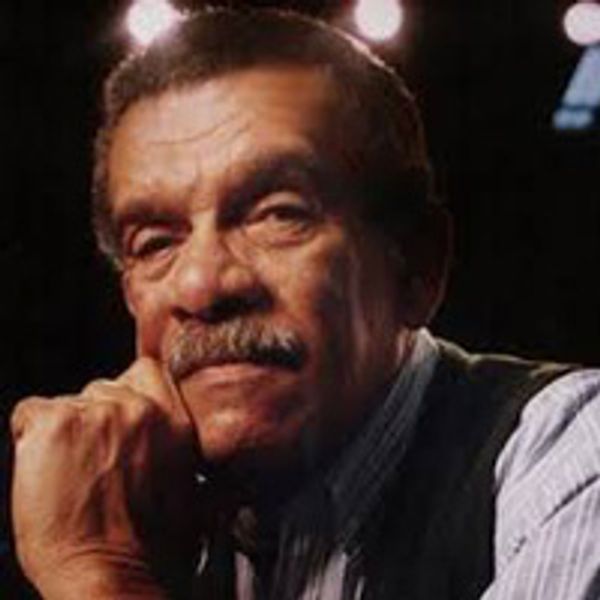

Derek Walcott

Derek Walcott (1930–2017), awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1992, published more than forty plays and poetry collections in his lifetime, including White Egrets (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2010) and Selected Poems (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2007). For twenty-seven years he was a member of AGNI ’s Advisory Board.

Louis Bourne’s interview with Walcott, “Just a Fisherman: Derek Walcott on Omeros,” appeared in AGNI 50. Walcott’s book-length poem Tiepolo’s Hound was reviewed in AGNI 52 by Diane Mehta.

Five days after Walcott’s death in March 2017, AGNI founder Askold Melnyczuk joined a conversation on the radio show On Point about the laureate’s life and poetry.

Order AGNI’s limited-edition broadside of Walcott’s “A Sea-Change.” The poem was first published in AGNI 67 and later reprinted in Harper’s and The Best American Poetry 2009.