Lia Purpura, Wasp Nest (detail), featured in AGNI 102

The Pied Piper of Fuckit

We built the Squirrel Tormenting Device by strapping a lawn sprinkler and hose to a remote-controlled toy truck that Dunnigan had picked up at a yard sale. For the Intermediate Range Ballistic Car Wash, we made a catapult out of PVC pipes, then put it to use lobbing water balloons at Dunnigan’s pick-up truck in the parking lot behind the closed-down candy factory. The Spousal Warning System was a wireless webcam we hooked up to a tree at the entrance to our subdivision so that we could always know exactly when our wives were arriving home from work.

I was then forty-seven years old; Dunnigan must have been in his mid-fifties. He was the one who came up with the ideas; I sat right down and began sketching plans to turn them into reality. The unemployed editor and the unemployed engineer: right brain, left brain. Under different circumstances, we might have gone into business together, maybe even made it a success. Instead, we wound up digging the Tunnel.

~

Daphne and I had bought our place only a few months before Dunnigan and his wife moved in next door. None of us knew it at the time, but in the previous year those two houses had been the setting of notorious neighborhood scandal, the husband from my place carrying on with the wife from his. This affair ended loudly, the men swinging baseball bats at each other on the front lawn while children waiting for the school bus screamed in horror. One of the rivals, the story goes, ended up in the hospital with a fractured skull, but not before taking out all the windows on his enemy’s minivan. I don’t know if either marriage survived, just that both couples moved out in a hurry. For months the houses stood empty at the end of the cul-de-sac, matching for-sale signs along empty driveways, lights switching on and off with creepy concurrence, as though hooked up to the same automatic timer. By the time we moved in, the two places had become permanently linked in people’s minds: they were the subject of gossip and curiosity, even derision, as if the structures themselves had done something tawdry and shameful.

I’m not sure if knowing this chapter of local lore would have stopped Daphne and me from buying the place, but there have been times since when, despite my grounding in the rational world of applied physics, I sincerely wondered whether the house was cursed. We bought it after the youngest of our two boys headed off for college, leaving us alone in our previous home, a four-bedroom ranch-style with a garage full of forgotten bicycles and a patio cluttered with skateboard ramps. We told ourselves that we needed to simplify our lives and free up capital for tuition, but I think that old house made us aware of a silence between us, one we hadn’t really noticed until the kids were gone. In any case, we barely broke even on the move. Although the new place—a faux arts-and-crafts bungalow—was smaller, it was in one of the most exclusive subdivisions in town, our backyard bordering a thickly wooded forest preserve that gave us a sense of living in the country. We were only the second occupants of the house, its kitchen gleaming with new appliances, its basement still smelling faintly of the carpet showroom, its master bathroom taking up more space than our old den. After years of struggle and compromise, Daphne and I told ourselves we were finally where we belonged. Seven months after moving in, I lost my job. Then came Dunnigan.

~

It did not take long before I realized the man next door was also spending most of his time around the house. Not that I cared. Within the span of a year and a half, our town in the outermost suburbs of Chicago had lost three of its biggest employers: the pharmaceutical firm shut down its research facility, the bank outsourced its call-center operations to India, and my own company, a maker of medical devices, moved its product-testing division to China. The sight of well-kempt middle-aged men killing time at the library or tending gardens or pushing carts around the supermarket in middle of the afternoon had become all too familiar. For the most part, we averted our glances and tried to ignore each other.

I had until then only exchanged a few words with my neighbor, a short, round man with hound-dog eyes and a random swirl of thick white hair that seemed to defy whatever attempts, if any, he made to give it order. A tall wooden fence separated his yard from mine, so I knew almost nothing about his comings and goings. But on the bright spring morning that welcomed in my sixth month of unemployment, I decided to make myself useful and clean the rain gutters. Climbing the ladder, I heard the sudden growl of a gas motor and, turning to investigate, found myself with a clear view of my neighbor’s driveway, where a strange scene was unfolding below me.

Dunnigan was fidgeting with a backpack-mounted leaf blower, which weighed down his round shoulders and made him look like a squat, disheveled spaceman. There were no leaves in sight. At his feet were a six-pack of beer, one can of which already lay crumpled on the asphalt, and a wooden basket of what appeared to be tomatoes. As the machine roared on, he bent down, cracked open another can and took a sip. Then, aiming the leaf blower down the driveway with one arm, he grabbed a tomato and loaded it into a feeder tube that was duct-taped to the base of the nozzle. The tomato squirted out in a soft arc, skittering onto the asphalt fifteen feet away and rolling to a stop.

Many times since, I have wished that I climbed quietly off that ladder, saving what I had just seen for Daphne, an amusing tale to keep the conversation going when she came home from work, tired and tense. Instead, I shouted down to my neighbor. He cut the motor and looked up at me with his jowly face, lips parted in a gap-toothed grin.

“I’ve just got to ask,” I said. “What are you trying to do with that thing?”

“This thing? You, sir, must be referring to The Airzooka.”

“The what?”

“A cutting-edge weapons system, my friend. In fact, you have just witnessed its initial field trial,” he replied, waddling down the driveway to retrieve the bruised tomato. “Though let’s be frank: Delivery to the Pentagon is not imminent.”

I found myself laughing, something I hadn’t done much of in the recent past.

“Just out of curiosity,” I said, “what’s the muzzle velocity of that blower?”

“Muzzle velocity?”

“Yes, the m.p.h. The maximum air velocity at the tube.”

“Are you suggesting, comrade, that the device lacks proper propulsion?”

“I’m just asking.”

“I don’t know, to be honest. Do you think it might explain the, er, limited range of my obviously phallic contraption?”

“Could be a lot things. Perhaps your obviously phallic contraption is just too short. Generally speaking, the longer the gun barrel, the higher the velocity.”

Dunnigan let loose a happy snuffle. “You, sir” he said, “seem to be a man of considerable technical expertise.”

“In a past life, I was a mechanical engineer. Then I went into management. Now I’m what they call redundant.”

He tossed the tomato into the bushes, then peeled a beer from the six-pack ring and held it up as an invitation. “Now, now, no self-pity. Come down, friend, and discuss your future. There’s a place for you in the fast-growing Airzooka industry.”

That was how our friendship began. Or perhaps collaboration is a better word, since, other than our inventions, we never had much in common except our lack of employment, which we rarely discussed. We spent that first week experimenting with the Airzooka in the forest preserve, where we shot off bushel after bushel of tomatoes, with some kiwifruit thrown in for good measure, until we had the thing more or less perfected. That got us thinking about other possible adaptations for the leaf blower. Among our more successful efforts were the Festooner, a device that shot toilet paper into trees, and BloPolo, a game played with a beach ball and old bicycles from my garage. The Aircordion, a high-powered version of the instrument familiar to polka aficionados, was a technical and musical failure, though it did provide many hours of amusement.

We never told our wives about these undertakings, never mentioned the Crossbow Powered Kite Launcher or the Hidden Trap Door Beer Cooler or the Feline Chariot Races. We did not even let them know that we had begun to spend our afternoons together. I was not normally the type of man who kept things from his spouse, and to this day I’m not sure why I never told Daphne about my adventures with Dunnigan. At the time, I suppose, it all seemed pretty simple. If I had revealed how I was wasting my days, she would have demanded that I stop. And I was having too much fun to let that happen.

~

On our mantelpiece back then there was a fading color photo of Daphne and me from the early days of our marriage, a nighttime scene by a lake. Her face, full of summer freckles and shadowed by a wide-brimmed raffia hat, is turned to me as she gazes up in mock adoration. I’m looking into the camera, head at a cocky angle, lips fixed in a smirk, eyes crimson in the flash. We both look impossibly young. My right arm is bent at the elbow, biceps straining, a couple of my fingers hooked into the gills of a huge mud-colored fish.

Daphne’s father took that picture at the cabin he used to own a couple hours north of here. I had just broken the family record, reeling in a nineteen-and-a-half-pound channel catfish, an event that marked the first and last time the old man took a sincere interest in anything I did. We drank vodka tonics together on the patio, talking about golf and slapping at mosquitoes while he skinned and gutted the fish. Later that summer he was diagnosed with cancer, and after he died Daphne’s mother sold the place. We never went back, and I have never gone fishing again. Nor, until my first few weeks of unemployment, did I give that photo much thought. But in those long empty days before I met Dunnigan, I often found myself standing before the mantelpiece, lost in the past.

I remembered how that fish had suddenly emerged from the murk, so massive it seemed otherworldly, obscene; how Daphne and I laughed at the sight of it, as if the creature had only been put in that lake for our amusement; how we kept laughing even as I ripped the hook from its mouth and beat its head over and over against the side of the boat; how powerful I felt doing that; how beautiful Daphne looked in those final seconds of dusk, the fading light on her long neck; how darkness came and we rowed to shore, still laughing, sure that this bounty was the first of many, that whatever existed in that black water beneath the boat was ours for the taking.

I can’t say when Daphne came to the conclusion that I had stopped looking for a job; perhaps it was before I realized it myself. My severance package had included “career transition services” with an outplacement company that helped executives and middle managers find work. Its offices were near the hospital where Daphne did corporate fundraising, so a couple of days a week I would put on a suit and tie, grab my laptop, and ride in with her. This ritual seemed to give her a sense that nothing much had changed, that the comfortable future we had always envisioned was still out there somewhere. She would flirt with me, hold my hand, talk about the vacations we would take once things got back to normal.

Things did not get back to normal. The outplacement firm, which occupied the former offices of a failed software company, was supposed to offer us a semblance of our old corporate life, but with its soft lighting and pastel walls and unremitting cheerfulness, it reminded me of the hospice where my father-in-law had spent his final days, coughing up blood. Many of my old colleagues were there, and we tried to keep ourselves busy, calling potential employers, emailing resumes, and attending PowerPoint presentations with titles such as “An Optimistic Front is Essential.” Nobody found work.

I stopped going there even before I met Dunnigan. By then, my severance was about to run out. Daphne did not panic; it was not her style. She worked with our financial consultant to free up some cash, took out a new line of credit, and made sure our boys applied for student loans. In the old days, I would have been in charge of such projects, but by now Daphne was getting used to making the financial decisions and I was strangely happy to let her. She had begun to treat me like something of a third son—the grown-up deadbeat who mostly got in the way.

“Maybe you should look for a part-time job, something to exercise your mind,” she said one night as we lay in bed.

“My mind is strong. Never better.”

“I’m really starting to worry about you.”

“Don’t. I’m perfectly content.”

“That’s what worries me.”

The conversation broke off. She was too exhausted to continue, and my head was racing with plans for the Tunnel.

~

The idea was simple enough: Dunnigan and I would build an underground passage between my basement and his. It came to us—or rather, to him—one afternoon as we sat around my TV room, drinking beer and brainstorming while the all-news channel flickered faintly on the screen. We had been looking for something big, a project that would test our intellect and tax our energy, but until that point all our schemes had proved impracticable. I was, in fact, just telling Dunnigan that his idea for a Laser Hedge Trimmer was an unworkable fire hazard, despite its theoretical potential to revolutionize the topiary arts, when he suddenly whirled to face the television.

On screen was a grainy video of a thin and irregular passageway, the walls carved from clay, the only light provided by a bare bulb in the low ceiling. This crawlway, we learned, had been used to smuggle Mexican workers into the United States. The reporter closed with a flourish: “No one knows how many people have made this subterranean trek, leaving their past at one end of the tunnel in search of a new start at the other.”

Dunnigan darted up and switched off the television. Then he stood over it, staring at the blank screen, fat little fingers combing hurriedly through his white hair.

“Why didn’t we think of it before?” he said.

“What? A tunnel?”

He turned to me slowly, his face pink with excitement. “No, my friend, not just a tunnel. An escape.”

He began to pace the room, flapping his little arms for emphasis as he talked. “Steve McQueen and James Garner—now, those fellows gave the Nazis a taste of American ingenuity! Hogan’s Heroes! The Count of Monte Cristo! No, my esteemed fellow inmate, these walls cannot hold us. What a lark! Oh, what an epic lark!

Even then I knew that this wasn’t just another one of our practical jokes. Dunnigan knew it, too. The irony disappeared from his voice as he formulated the plan; I even detected a hint of menace as he tried to convince me of its merits. I hesitated at first, aware, I suppose, that I was at a point of no return, that the Tunnel would lead me all the way into Dunnigan’s world and away from my own. A week later, we were smashing a hole in the floor of my laundry room with a rented jackhammer. It didn’t matter that the “escape” he was proposing meant leaving one basement for another in the same subdivision. I just wanted out.

~

We dug a vertical shaft ten feet deep, shored up the walls with timber and plywood, and threw a pallet on the floor so mud wouldn’t accumulate. At the bottom of this pit, we began a horizontal crawlway toward Dunnigan’s place. One of us would dig, using a small shovel or mason’s brick hammer to chip away at the clay. The other would haul off the loose soil in polyethylene sandbags and stack them on the laundry-room floor, which we had covered with plastic. At the end of the day, we would load the bags from the basement window and dump them in secluded parts of the forest preserve. Then we would clean up the laundry room, put all our equipment in the pit, close the plywood trap door, and unroll the wall-to-wall carpeting back over the entrance.

I am quite certain Daphne never found evidence of the Tunnel—which is not to say she was unaware of my attempt to escape. She had been urging marriage counseling, an idea I battled off with procrastination, promises of change and a prescription for anti-depressants, which I quietly stopped taking after the first week. I did not underestimate the pain I caused her, but I could also see that despite my withdrawal, or even because of it, Daphne was becoming stronger, more resourceful and in some ways happier, confident in her new responsibilities, liberated from her old of bonds of motherhood and home. She had joined a book group, begun making new friends. I knew that she worried about me, of course, and that she missed my income. But she no longer needed me—or at least that is what I had convinced myself.

What went on between Dunnigan and his wife I will never know for sure. He rarely mentioned her, and I only met the woman a few times. They were an odd couple, I’ll say that much. She was four inches taller than her husband and perhaps fifteen years younger, an attractive if unsmiling tax lawyer who did not seem to fit the name Blithe. He told me that they had met while walking their dogs but that after they were married she decided she was allergic to them. One day, he came home to find that she had put down not only her own schnauzer but also his beloved golden retriever, Chairman Mao. This had happened five years ago, but he still had not forgiven her. It took me a few weeks to realize that despite his wicked sense of humor, Dunnigan was a man of many fierce grievances, most of them unstated. He once mentioned a couple of adult daughters from his first marriage, but when I asked about them he waved me off. “Goneril and Regan don’t speak to the old king anymore,” he said. I never learned their real names.

He was only a little less secretive about his newspaper career, which, I came to know, had ended when he took a buyout from his employer of twenty-eight years. I sensed that his departure had been a bitter one and that he missed the job a great deal. But if so, he wasn’t talking about it. “I’m past my prime in a profession that’s already dead,” he declared on that first day of digging. “But what of it? Do our current endeavors not stimulate the mind and delight the senses? The Tunnel—this is our work now.”

~

His mood soured dramatically in the second week, which at the time I attributed to our lack of progress. We kept hitting rocks, hunks of bizarrely shaped granite that seemed like three-dimensional Rorschach tests: toasters and teapots and fire hydrants. We had to break them up or pry them out; some were so big we ended up curving the passageway around them. Dunnigan had no patience for any of it. He had grown sullen and irritable, and for the first time since I knew him he made no attempt at gallows humor. I would hear him ahead of me, cursing in the dark, and as I crawled down the shaft to collect another bag of soil my headlamp would catch his filthy face, eyes gleaming with malice as he hacked away at the earth.

In the beginning we had traded jobs regularly, but by now Dunnigan did all the shovel work. With his bowling-ball body and a mining helmet perched atop his nest of white hair he looked like one of the seven dwarfs. He dug with a fury, as if the mother lode lay just ahead. The air was thin and Dunnigan stank to high heaven. We didn’t talk. All that existed was the work; everything else dropped away.

On the tenth day, Dunnigan went up to get lunch and, exhausted, I crawled into the passage, stretched myself out on the cold ground and switched off my headlamp. Darkness smothered everything. Perhaps I fell asleep or perhaps my mind just shut down. Then my cell phone rang. I answered, not thinking how strange it was to receive a signal underground. It was a man from the outplacement company.

“I’ve been trying to reach you all morning,” he said. “You have a job interview tomorrow.”

~

We had agreed to shore up the tunnel with wooden uprights and crossbeams at four-foot intervals, but this consumed a great deal of time, which Dunnigan now insisted would be better spent digging. When I reminded him of the risks, he just snorted. “Aren’t we here to test our mettle, old friend? Isn’t a bit of danger all part of the jape?”

In the end, he refused to do anything but excavate soil, so I was left to build the bracing myself. It was a two-person job in the best of circumstances, and within a few hours, several yards of unsupported passageway loomed between us. I was on my back, trying to push an upright into place, when I felt the earth give way ahead of me.

Scrambling down the tunnel, I found Dunnigan lying on his side, his head and shoulders buried beneath a heap of clay. It was hard to wedge my way in to help him, and he seemed to fight me, kicking his legs and twisting his fat frame. I burrowed with my hands, pushing away the clods as he gasped for air. We lay inches apart. His eyes were caked shut, and under the glare of my headlamp his clay-covered face looked like a death mask. He spit, licked his lips, drew a deep breath.

“Oh, well, old friend,” he sighed. “Back to the mines, as they say.”

~

Daphne was about to start her morning commute when the phone rang. I had been offered the job. She sat down in the middle of the living room floor and sobbed with joy. Somehow this surprised me.

I was worried about how Dunnigan would react, but he took the news with an air of cool resignation, as if he’d been expecting it sooner or later. “Bully for you—a return to life above ground,” he said. “The truth is, you’ve been spending far too much time with the Pied Piper of Fuckit. The cave door was about to shut.”

We divided up the tools and closed the tunnel one last time. It was all very lighthearted, just as it had been on that first day we met. When we shook hands and parted ways, he told me he was going home to cut the grass. I said I doubted that very much. A few minutes later, I heard the sound of a mower on the other side of the fence.

The job was with a subcontractor of my old company. Its salary was lower, its hours longer, its benefits nonexistent, its headquarters seventy miles from my house. I was amazed how quickly I readjusted to the rhythm and pace of that world, how easily Daphne and I slid back into our old habits—the way she checked my tie every morning to make sure it matched my shirt or the way she sent text messages during the day to find out how some inane meeting had gone. We rarely spoke of the recent past. I did not avoid Dunnigan, but I didn’t see him, either.

Three weeks after I began the job, we went to dinner at the house of some friends a block away.

“What’s that alcoholic neighbor of yours going to do now?” the hostess asked.

“Who?” said Daphne. “The short guy next door?”

“Yeah, the one with the pretty wife who moved out on him.”

“Just recently?” I asked.

“No,” the woman said. “A month and a half ago. Where have you been?”

~

The next time I saw Dunnigan, he was standing in the hallway outside my bedroom door, half-hidden in shadows. Daphne slept next to me in a pair of flannel pajamas. It was four in the morning. He cracked that smirk, and for a moment we just stared at each other. I can’t say I was entirely surprised to find him there.

He retreated into darkness; I pulled on a bathrobe and followed. I found him sitting in the TV room, a beer in his hand, his face lit by the all-news channel. He had lost weight, put on muscle. One of his front teeth was missing. His stench was indescribable.

“I see you’ve finished the Tunnel.”

“This is just the start,” he said, without turning from the screen. “I’m still digging.”

“Why are you here, Dunnigan?”

“Because I want you to see it,” he said, turning to me with bloodshot gray eyes. “Come away with me, old friend. Come away.”

“I’m done with all that.”

“No, brother. Come see what I’ve done. A quick look.”

I followed him to the basement, not understanding why, not knowing what would happen next. I felt numb. He clambered ahead of me into the hole and soon disappeared around the first bend, waving for me to follow. I cannot say I wasn’t tempted.

“Dunnigan,” I hissed. “Wait.”

“Hurry along, friend.” The voice already sounded distant, muffled by the earth.

For a few moments I hesitated, my bare knees pressed into the cold clay. Then I turned around and scrambled out of the passage. Back in the basement, I closed the trap door, slid the washing-machine over it, and set to work bolting the thing shut—by hand, so Daphne wouldn’t hear.

Later, I stood in the hallway where Dunnigan had stood so that I could watch my wife sleep. Her skin looked ashen in the first light, and her face, pressed up against the pillow, was deeply lined. I could see what time had in store for her. For a moment, I felt nostalgic for that beautiful young woman in the picture on the mantel. Then I climbed back into bed and wrapped my arm across her chest.

~

I was on a business trip when the marshals came to Dunnigan’s house and piled all his belongings on the front lawn. What amazed everyone in the neighborhood was how little furniture was in that big house. He didn’t take any of it, just grabbed some clothes and a few boxes of books and drove off. Nobody heard anything about him after that.

Once again, there were for-sale signs at both houses at the end of the cul-de-sac. During all those months, Daphne and I rarely raised our voices at each other, but after things got back to normal we began to fight. Her rage shouldn’t have surprised me, I suppose, but it did. I was stunned when she announced that she was moving out.

I don’t think either of us knows what comes next. Daphne likes to point out that with the boys at school there’s no reason for us to be together unless it’s what we really want. I’m trying to convince her that it is. In the meantime, we’ve moved into separate apartments and put the house up for sale. Neither of us has fond memories of the place.

I waited until my last night there to pour new concrete in that corner of the laundry room. It wasn’t my intention to undo the bolts on the trap door, but I remembered I’d left some tools in the shaft. There I discovered my helmet, so caked in clay it looked like an ancient relic. The headlamp still worked.

The passage seemed more cramped and serpentine than I remembered, and it felt like a long time before I reached the place where my own work left off. After that, the crawlway became even tighter and less uniform, as if scratched from the earth by a burrowing animal. At times I had to get down on my belly and scoot in a soldier-crawl. There was nothing to shore up the roof: The whole thing could have collapsed at any second, but there wasn’t enough room to turn around even if I had wanted to. At last I came to the end of the passage and saw the shaft leading up to Dunnigan’s basement. He had left an old ladder against the wall, but when I climbed it, the trap door wouldn’t budge. I tried ramming it with my shoulder but almost fell off the ladder and decided to give up. I was on my hands and knees, about to start the journey back, when I noticed the tiny entrance to a second passageway heading off in another direction. I squeezed inside and crawled along it for several minutes until it forked into two different shafts. Taking the one to the right, I soon came to another fork and then a third. The air grew thin. I thought I heard noises, little percussive echoes, and was suddenly struck by the hope that Dunnigan was up ahead somewhere, still searching for a way out. I pushed on, wondering where it would end, but the Tunnel always outstretched the reach of my lamp.

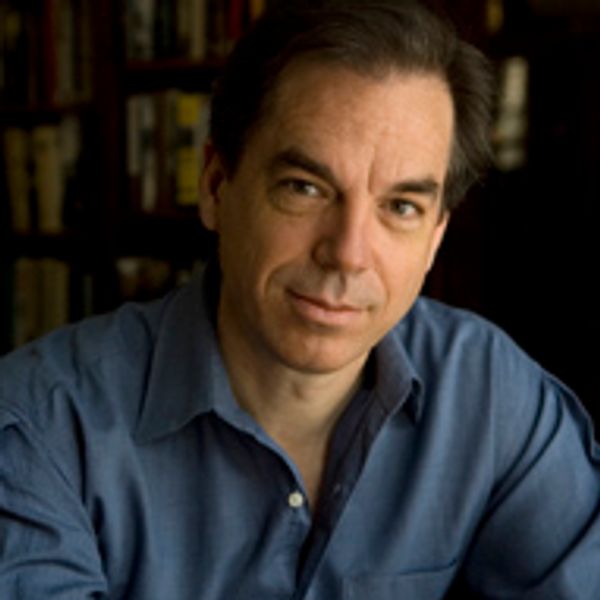

Miles Harvey

Miles Harvey is assistant professor of English at DePaul University. His stories have appeared in Ploughshares, The Michigan Quarterly Review, Fiction, AGNI, The Sun, The Sonora Review, Nimrod, and other publications. His nonfiction includes The Island of Lost Maps: A True Story of Cartographic Crime (Random House, 2000) and Painter in a Savage Land: The Strange Saga of the First European Artist in North America (Random House, 2008). His website is www.milesharvey.com. (updated 4/2011)