Lia Purpura, Wasp Nest (detail), featured in AGNI 102

Feeling Satisfactory

Assembly line jobs and 4 a.m. wakeups, the merry-go-wife-around, pay-packet explanations to his mother are things of the past. His mother who believes that mental illness has no effect on intelligence, feels he ought to try afresh for a career in computer engineering. “I am thirty-five,” he tells the counselor.

The counselor is worried about the effect of the injections on Moses but can’t do much. His supervisor is an immigrant from China, a widely published author, extensively qualified, with a thing about family communities, and his patient’s wife has strong ideas about Moses being crazy. Moses’s behavior doesn’t help. The boy—Moses’s nature makes it difficult for the counselor to think of him any other way—has been putting on weight and is scratching at open sores around his mouth. The neck muscles used to be thick from laboring jobs on assembly lines, but now the burnt olive complexion turns sallow and the wire-brush hair is graying. The boy might be slow in working out the usual meaning of life, but he knows his movies back to front. Interspersed with a diet of cops-and robbers videos are arthouse films like Solenz’s Happiness. On a whim, he will go down to the Palace Theatre for a season of film-buff recommendations. Moses has been an education for the counselor.

“My time’s up?” Moses gathers the leaflets on his lap and drops them into the counselor’s bin.

“Do you want to make another appointment?”

Moses is going to say no and then he says yes. He believes the counselor enjoys their talks. Life inside these four bureaucratic walls must be unbearable without some kind of relief. Today they discussed Memento. “I should be a film producer,” Moses tells him. “Easier than computer engineering, don’t you think?” He wants to hug the counselor but controls himself.

Down in the mall, he buys postcards from a gift shop where the shop assistant knows him—Moses is a frequent customer—and gets a wish you-were-here card upon which he writes a poem about loneliness.

The plan is to spend the day on the trains—something he would not have been able to do before he became crazy. The well-being of platforms all over Melbourne could be seen as his challenge and he takes it upon himself to pick up and dispose of litter. Better than going home to his mother, who will tell him to be careful of girls.

~

The prostitute in the Dalmatian jacket fails to exit at Balmain Hills. Already she is late, having missed an earlier train. She is feeling really pissed off at Moses dropping in when he feels like it and taking up husbandly duties even though she’s already told him that he’s not the father. The ratface went ballistic about leaving Tweetie sleeping with her tiny hand leashed to the bedpost. Moses has wormed into her good books by offering to do her ironing every night, and yesterday she felt sorry enough to let him sleep on the sofa. Tweetie might start coughing again, he said. She needs to talk to the counselor about the medication.

At the next station, she lights a Marlboro and walks towards the platform telephone, pulling at a short leather skirt. She hunches over like a boardwalk model, hands folded over in front, right over left holding the cigarette.

She jerks at the cord like a tethered goat as she fishes her twenty cents back. Her coins keep falling through and the number for Faults rings out.

A train arrives. She grinds her cigarette underfoot. Perhaps she’ll give work a miss and go home. At Balmain Hills, the station loudspeaker announces that the train will be going back to the other side of the Dandenongs. She says shit again under her breath. Why not report to the other center? Bound to be work there as well.

~

Moses sees his wife when he gets on the train.“Hey, how are you?”

The prostitute pretends he is invisible, shifts a wad of gum inside her mouth and blows a blue bubble. She relents. “Hi.” Her lips lift briefly at the corners. Black mascara, high shiny cheekbones, and a sceptical look, that’s Sue-Anne. She is no longer his wife, Bharati. She has chosen to transcend her cultural inheritance and become a real Aussie battler,a Sue-Anne. Her hair is tied carelessly with a rubber band. Except for the high style of the coat and long boots, she could be any suburban girl heading into Flinders Street. Moses gives her the postcard.

“What are you doing today?” he asks.

“Using shit public transport. What about you?” From her handbag she extracts a tube of what looks like lipstick. She smears the open end under her chin all the way up behind her ear. Watching her fix her face, Moses longs for the days when he was married to her and life seemed simple. The sun highlights red over her hair with every jerk of the carriage. She puts in the unopened postcard and the tube.

“I was going to your workplace. Are you heading there?”

“Yes.” She is not encouraging.

He wants to know if she will get remarried soon, and to ask about Tweetie; whether the thought of her child makes her happy. Instead hesays,“Have you seen the movie called The Thin Red Line.”

“No. Is it good?”

“It’s a war movie.”

She makes a small movement with her shoulder. “I wouldn’t watch it then.”

“It is not the usual kind of war movie. I recommend it.

“I don’t have spare time,” she says in an injured fashion.

“Do you cook at home?”

“Sometimes.”

He used to love feeding her freshly baked pumpkin muffins left on the formica kitchen bench at 4 a.m., extras Glad-wrapped for his morning tea, Swiss chocolates bought on his way home, palak paneer from the Indian shop that he had learnt to make just the way she liked with real milk and muslin to press out the whey.

“Have you been to Hot Peppers? The chef has mixed Western and Eastern philosophies. I spoke to him personally.”

“That’s good.” She looks restlessly out the window and notices the platform sign for Bayswater come up. “See you,” she says.

He comes to a change of plan since she doesn’t seem to want him around. “Have a good day,” he calls out. He doesn’t need to spend his money at the brothel after all. On occasions when his wife and child seem too far away, he can blow an entire Social Security check buying her services—she is happy to provide once it’s paid for—and live on handouts for the fortnight.

~

At Belgrave, the final stop for passengers, he fumbles through his wallet and back pocket to find twenty-cent coins for the telephone. If he had his fishing rods, he could have gone into the city and then outto the seaside—he does not want to go back home and get them. He knows from experience that his energy will be depleted if he backtracks. Besides, today might be the day when his supervisor comes around from the hospital with the injections. Moses doesn’t want to spend another week trembling, convulsing, and unable to speak.

He stands on the platform in a state of indecision. Despite the cold, he is wearing only a white polyester T-shirt and shorts. With his face set in a frown, he walks up the overhead pass and down to the main street. He has money for a taxi now but if he saves it perhaps he can take his sister’s family out to the movies…if they don’t piss him off by being busy.

Up from the roundabout and the Puffing Billy signs, the road leads to an entry for Sherbrooke Forest. Sucking on the can of Coke bought in the main street, he goes past chocolate box homes, eucalypt stands, and a fern kingdom. Sweat beads his forehead and runs down his nose as he trudges uphill. His yellow urine against a huge bole of a mountain ash steams up the air with medicinal notes. Soon he falls into a rhythm, moving in a dogged fashion. He stops briefly to talk to a bird no bigger than a large butterfly.

“You know,” he tells the bird, “Jeremy Irons was brilliant in Lolita.”

The butterfly impersonation cocks its head and flaps pale green wings. It lands at his feet and pecks into earth recently churned up by a lyrebird. Moses takes this intimacy as a good sign but further discussion is made impossible when the bird has to leave on important business.

Forty-five minutes later, he exits at the picnic grounds where children feeding rosellas put a smile on his face. He turns down a twisting road towards Kallista. An hour or so downhill from the rhododendrons,he passes the primary school in the mainfare and keeps going; at the milkbar he misses turning towards Ridge Road and keeps plodding towards The Patch; a deeply rutted lane veering off to his left stops him in his tracks. I know this corner, he says out loud. There was a Mobil service station here. Amazing there’s no sign of blood from the time that guy went on a spree with a shotgun! They’ve done a bang-up job of restoring it to a natural style. Great trees. Man, those ferns are beautiful! Reminds me of the old country. I wonder if they can grow chillies around here. Half an hour later he comes to Patch Valley proper, and outside a homely rambling cottage he finds fruit, eggs, and corn set out with a money box.

He cracks two eggs into his mouth and smacks his lips. Then, with a bag of Jonathan apples in his hand, he goes into the house to ask if he could pay for the consumed part of the dozen eggs.

“Sure,” says a woman with varicose veins. A cocker spaniel bitch chases her litter of five pups up to his feet and looks fiercely matriarchal.

“You are lucky,” he tells her. “This reminds me very much of my childhood.”

“Are you from around here?”

“Oh, no, ma’am, I’m from far-off parts. But I’d like to come back and buy one of your pups.”

“I’m sorry, they are not for sale.”

He sketches a mere gesture of a salute and leaves.

~

Five hours after leaving the station he arrives at his sister’s house in Oceanview Crescent.

“Hello, Anu,” he says when she opens the door.

“How did you get here?”

“Walked. Hey, have you got something to eat?” His standard question at her house.

“I suppose something can be made. Shoes off.”

The children—eight, ten and twelve—rush over and give him hugs. The youngest girl sits on his knees while he jogs her. She runs her hands through his hair, dislodging dandruff and gel. Anu frowns.

“Hey.”

His sister is rinsing a bowl at the sink. “Yes?”

“Do you think Social Security would advance me a thousand dollars.”

“How would I know? What do you need it for?”

“Mummy is going to hospital for two weeks and I need a place to live.”

“What’s wrong with staying at home?”

“Nothing.” He part-owns the flat he is paying off with his mother’s help. His chin juts out and the youngest girl scratches under there like he was a cat. “I will get lonely. I don’t think I’m going to manage by myself.”

“So this money is for?”

“To stay at the brothel.”

Anu stops and puts her hand over her mouth.

He takes offence. “What are you laughing at?”

“If I don’t laugh, I’ll cry.” She hands over the plate of reheated pumpkin curry and calls out to her husband, who is building the open fire in the lounge. “Guess what Moses wants to do?”

“Not funny.” Bharati’s career choices are not for others to judge.

“Of course not.” Her voice is careful.

“Not funny.” The little girl parrots his words and clips him lightly over the ear.

“Hey,” he says to the child, pointing with his unused fork, “How would you feel if your school friends made fun of you like they did when I was little.” The little girl mimics how would you feel but is pulled off his knees by her mother and sent to draw in her bedroom.

“Sis.”

“Yes?”

“Would you do something for me if I gave you two thousand dollars.”

“And where do you have that money? I thought you just told me about borrowing . . .”

“Never mind.” He waves her questions down. “Would you?”

“No way are you going to get a reconciliation, Moses.” He has been separated from Bharati for five years.

“Why won’t you help me?”

“Let’s not get into that again. I can’t believe that we are even talking about a woman like her.” She bangs down the saucepans into the drawers and flings dry cutlery into their trays. “Mummy is pissed off,” says the oldest girl from the doorway. Anu yells at her daughter for using the P-word and her husband comes in and tells her to go easy on the kids.

“She said that she would let me date her if I sign over my share of the house,” Moses explains.

“What a bitch!” Anu looks at her husband as if he is the cause of her troubles. Her delicate face takes on a charcoal tinge. “And I used to feel sorry for Bharati…or Sue-Anne or whatever the fuck her name is now! Imagine wanting to take your house away from you.”

“Aw, she isn’t really . . .”

“I warned Mother about arranged marriages. How can she expect to marry an intelligent girl to you? Of course advantage will be taken.”

“She doesn’t . . .”

“Let me ring my solicitor on Monday and get him to stop this illegal manipulation.”

“Please don’t do that.”

“How can you come here with your problems and refuse help? Look at what you’ve done now. How will I stop thinking about this disgraceful matter? And you don’t even care!” She takes her husband’s arm and goes out into the garden.

Moses sees her pointing to a pile of stones and her husband arguing some point and throwing his hands in the air. Moses feels iron weights settle on his eyes. There is something at his sister’s house that reminds him of coming home. He allows his head to loll back on the back rest and wakes in what seems to be the next moment, in a cold sweat, expecting to find an armored robot moving towards him brandishing his next lot of injections. He can hear the metallic clatter of the robot’s limbs. He wipes his forehead on his sleeve. Through floor-length windows, he can see a homemade plastic fountain surrounded by ferns and large stones. “Hey, have you thought of leaving nature to itself?” he asks no one in particular.

His lips have gone terribly dry and he goes to the sink for a glass of water. “My tongue feels thick.”

His sister nods and says, “If you want a lift to the station you need to hurry. I’ve got to be back to get organized for a school performance. And Moses, will you please be careful around that woman! The pair of you make me feel so helpless.”

“Isn’t that the human condition?” her husband says, looking up from the book he is reading.

“Don’t you start.”

Moses feels unsatisfactory again and is glad to have left unsaid his thought of taking his sister’s family to the films. He wonders if his wife will still be working.

~

Sue-Anne is on the verge of calling it a day when Moses asks for her. Her coat with the fur muffs goes back in the closet. She picks up some cushions from the floor and throws them on the bed. Her Marlboro Lights are in the closet. The lighter sputters three times. Shit. Bloody cheap shit from Taiwan. She lies down on the cushions, manages to light her cigarette finally, and flings one arm over her face and the other over the side to make it easy to tap ash onto the carpet.

How is she ever going to get some time off, a holiday even? With the Toyota breaking down so often and private-school fees coming up for five-year-old Bri, there’s just nothing left.

Moses comes in. She takes her arm off her eyes and tucks it behind her head. “Hi.”

“Hello, long time no see.” He pulls up a stool and sits next to the bed.

“Another coupla minutes mate, and you’d have missed out.”

“Were you going home?”

“Boy, I’m sooooo tired.”

“I am the man for you then.” He kneels down and starts massaging her foot.

“Mmmm.”

“Hey.”

“Yes?” She wriggles over to get the greatest benefit from the strong pressure of his thumb.

“Would you spend a couple of weeks with me for two thousand dollars?”

She squints at him. “You serious?”

“We could go to Surfers. I hear they do a good tandoori chicken over there.”

She sits up and props her elbows on her knees and her face on her palms. “Yeah, why not? You go for the chicken, I’ll lie on the beach. Sure about the money?”

“I’m a generous man.”

“Sure are.” She lies back with a sigh. Perhaps when she came back, Moses would cough up for a car that worked. The air would be good for Tweetie and she’d be able to follow the doctor’s instructions about keeping the baby off milk products. Jeez, what the hell was she going to do if Tweetie’s cough got worse? So far everyone gives her advice she can’t use. She falls asleep as Moses digs his thumbs into the hollow of her instep and dreams about making it with the baby’s father.

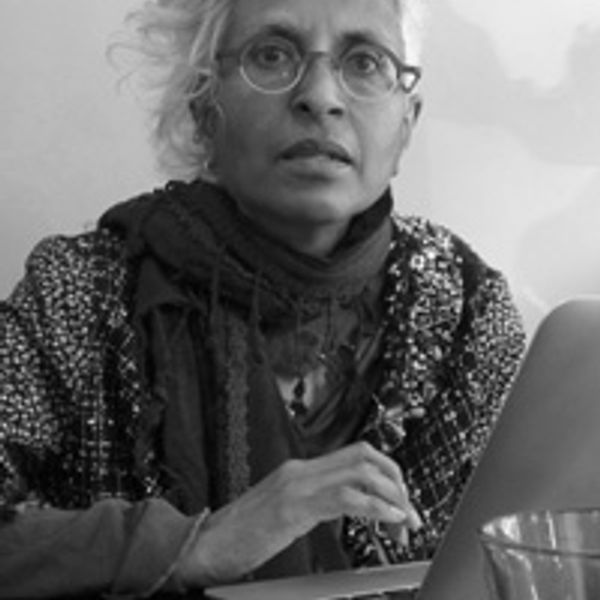

Girija Tropp

Girija Tropp is a winner of the Boston Review Prize and the Josephine Ulrick Literature Award 2006. She has been published in AGNI, Best Australian Stories 2005 and 2006, Fiction International, Mississippi Review, Denver Quarterly, and other magazines. Her Twitter handle is @girijawrites. (updated 11/2013)