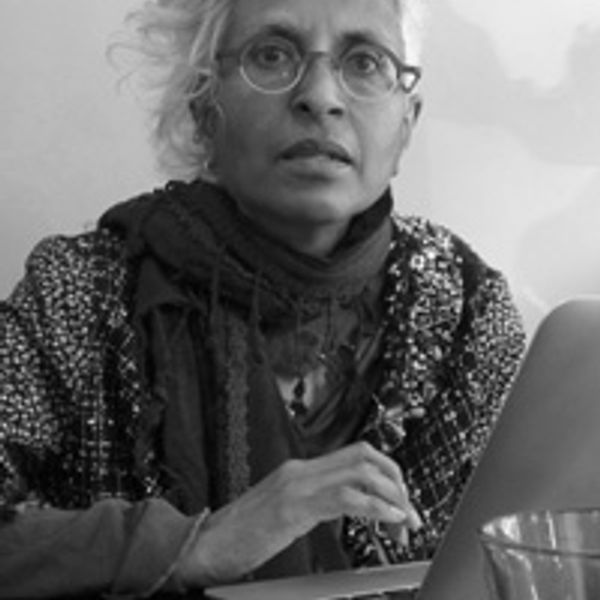

Malak Mattar, My Mother (detail), 2017, oil on canvas

Advent: A Traveler’s Tale

In the factory where I’d been sent to design a new brand identity, tired workers leant on broomsticks. An armless woman was eating buttons of what looked like chocolate, using dexterous movements of her feet. She held each button between her toes and nibbled. These people looked like hospital inmates. There were no air-conditioners in the middle of the desert.

“Could you help me understand Xtra?” I asked the woman.

The men who’d come over wanted to know my reasons. They looked at me suspiciously, perhaps because of my city clothes, my short skirt with its ragged hem.

“Because I need to work,” I said.

They leapt at me with syringes of the drug. Until just now, violence had never found me, always found someone else. “We are on the same side,” I yelled, but nothing. In the distance, a giggle. I bucked, was too strong for them; I ran through rooms, past different strengths of Xtra, resisting in each. In stereophonic headspace, my boss kept telling me, Stop living life as if you’re a sketch. I fled onto a roof barn and rushed down steps in a frenzy, before being captured. Again that awful giggle. The owner of the giggle launched into a song: However far away, I will always love you . . . Hilarious, being hounded by other wage slaves. As if the nature of human beings is to rip into whatever’s closest to themselves.

I was taken to my boss’s boss, the Head Evil Man, a Tom Cruise on steroids. He had china feet and a head that, inspected sideways, looked like a disk. “Hola,” I said, brandishing an invisible sword. “I want your slot,” he said, and asked me to take Xtra to enhance the experience. “Mediated love is the ultimate buzz,” he added. I sidetracked him by drawing pictures.

He went to a cupboard and peered inside. A young girl moved out of fetal position and strained to get her drug. I distracted him, said my tight slot did not need to be drugged. He was immediately interested.

But either he was too small or I was big. He said, “I can barely feel your slots.”

I called him back and took the shot of Xtra, which I found was 2-c-phenly-barbiturate to the power five. Xtra was a street name, like Big Mac or Chicken McNuggets. In keeping with what I knew, that belief was necessary for addiction, the drug had little effect. I rushed to complete my assignment so I could get out of the place. The Head Evil Man looked on with a peculiar smile, until finally he signed off on my proofs.

~

The city delivered me numb, like the aftermath of too many coffees, to my home in an outlying suburb. “Hello?” I called out, putting down my suitcase and closing the front door. No one replied. When I replayed the messages, my own voice came on, letting me know of my unexpected return. The rooms were littered with discarded clothes and used mugs, as if there had been a silent invasion. I flushed the toilet bowl, a half-smoked joint that I found in the bathroom. I washed dishes and put everything away. The cupboards were empty, there was no fuel in my car, and I was feeling jittery.

So I took his sports car, the one I’m not allowed to touch, and went looking for a supermarket that might sell something special. My desire for a treat bothered me, and every time I put my foot on the accelerator, the engine raced strangely. There had been a garbage strike, and the dumpsters were overflowing. I saw a puppy lost on a freeway, but when I did a U-turn, it had gone. A young woman cut in front and gave me the finger. At the supermarket, three people were lying in front of the entry doors with placards on their chests that said, We give a fuck about detention of children. Their mouths were taped. I bought them some bottled water. “At least you are up to something,” I said, and asked if there was anything else I could do. They looked from the bottled water to me and struggled to convey something important but could not get past the tape.

When I returned to the car, I saw the fender was badly dinted. Something odd happened in my chest. A tightness. My lungs felt tender. It hurt to breathe.

I sat with the keys in my hand, and two kids pulled up next to me and stared. They were playing heavy metal on superb sound systems. I looked at them, but they turned their faces away and sniggered. Perhaps I should go to work even though it was Sunday. In my mind, I was sketching these almost-men, elongating the lines of their car and framing the whole from within my own vehicle. There should be steam coming from the engine . . .

Stop all this extrapolation, I told myself. Where could my husband and children be? They had probably gone down to the beach house.

The evening sky had a red-orange glow from the smog. The expression on the boys’ faces begged for use as clues, also for ink and a watercolor wash. I had brought my briefcase because my wallet was inside, so I really could go to work. Suddenly I was more obsessed than ever to get to the drawing board—but could I work for a company that supported the marketing of a potent drug? I wondered which I would prefer: a world with detention camps or one with a happy drugged population. Tomorrow, I would hand in my notice and attempt a new path. There was no other way.

My husband would object. He would decide to leave me for the woman with the splendid legs and the voice of a cockroach. If that was the worst that could happen, it was not so bad.

I felt someone looking at me, but when I checked, the kids were pointing at the steam rising from the car next to mine.

~

The following months felt like having slices of cut lime inside my skin. The upside of being without a job had been my husband’s reaction. He promised to give up the cockroach if I would stay gainfully employed. In the midst of our arguments, he lost his sweet management-level position at the Ford factory—around the time my old boss rang up to say that the Head Evil Man was on his way down to have a word. Apparently my unique ability to touch the great Unwashed had been patently clear and it would be easier to change my mind than a million minds.

“Good and bad are only words for what people want or do not want,” the Head Evil Man said, puffing on a giant cigar.

“Isn’t it a bit tricky,” I replied, “to get involved in others’ wanting?”

“Tell me what you desire,” he shot back, “and I’ll make sure you get it.”

As my husband listened in to the meeting over a cup of coffee, he got an inkling of what I was up against. I don’t know if he would have understood without his job situation—a distressing personal downturn can make people receptive to new ideas.

~

To figure out what I wanted, I had to get away from what I didn’t. We needed a place to hide. The bad people, we heard, were trying to find us and were looking for something specific, like the recipe I’d taken away with me or the antidote I’d developed. At that time, we were living upstairs, above a specialty food shop where the cheese was to die for and the cranberry camembert was renowned for its flavour. The owners made cheesecakes with duck eggs; we were used to hearing the quacking of birds as they pecked at slugs.

Not only did we have to hide, we had to erase our footsteps and our friends had to erase their memories. There was madness growing around us like a fungus, and the only way out was to disinfect our memories. We travelled along strange roads and found a home, where we dwelt in a kind of anxious happiness. Then for some reason my husband turned nostalgic. “You are being selfish,” he said while packing his suitcases. Always the man, our friends would have said to make me feel better—because on the way back he met a woman, tall, willowy, feminine, and made bashful love in a barn. They made vows. He gave her a scrap of paper and thought it was harmless.

The woman, another version of cockroach, went home, and everyone could see the name of the man she had met. It was printed on her forehead, below her lip, and on the back of her hand. They knew she was a goner and that she would be found through her memories. The woman was glad to advertise herself because she had hopes of seeing my husband again.

The bad people found the antidote quickly then, and it taught them how to improve the original. Now there was nothing to stop Xtra from being a commercial success such as McDonald’s could only dream of—even though people had a tendency to bloat when they used it. The recipe was important in the war against terrorism, and also turned up in a cream for virility, so you couldn’t fault such a boon to mankind!

I was discredited, my family was lost, and the Head Evil Man gave me such a large dose of Xtra that my memories departed for fairyland. One of the things I did, before I took to foraging in the Carlton garbage bins for food, and while I still had some money, was to go to a detective agency and ask for help finding my parents. I had left them when I was sixteen and not looked back.

~

Acting on the agency’s advice, I went to a house along the lane, opened the screen door, and knocked three times rat ta tat and repeated it, and when a woman in a bathrobe and no teeth came to the door, I asked, “Who am I?”

“Nobody I know,” she said.

So I backed down the porch steps, turned, and kept going. There were too many houses to choose from, but I tried the tenth one along.

“Leave us alone or I’ll call the cops,” said a woman with a strawberry birthmark across her cheek.

“What are ya, Don Quixote?” The man climbing off the upended female in the back of the Ford panel van had a bottle of scotch in one hand and a chipped glass tumbler in the other. A flock of galahs were flying overhead, and their calls seemed to come back out of his girlfriend’s mouth.

When I arrived at my childhood home, I was surprised at the overgrown roses, the scent of which mingled with the dettol from the tiny suffocating rooms, and there were other things I remembered too, but the Xtra still had a firm grip on my mind.

My mother paused in the act of putting butter on her toast and called me an ungrateful child, and my father took me out into the garden and asked in a confidential whisper, “Have you been getting it lately? Because I haven’t.” We drank some beer together.

After a couple of hours, I went down to the river and leant over the edge and saw myself reflected, and it became clear to me that I was shaped like a woman with wavy edges. So I entered the water and swam for a while. I returned home, and when the police came to ask where I had been last night, and displayed a poster given to them by someone who looked like a movie star on steroids —they pointed him out in the newspaper—I told them that I was the woman with wavy edges. They took me to the cop shop, made a replica of my hand, and locked the door. I fell asleep and dreamt I was a horse in a commercial about Volkswagens.

~

It became obvious to me, once I was a connoisseur of garbage bins, that I craved something more, a way of life that everyone else seemed entitled to. “Ditto,” said the woman with broken teeth outside Safeway. So we made a joint decision to look for jobs. Before our conversation had turned serious, we’d been talking about curtains. She had pulled up a pleated brocade monstrosity from a street bin in South Yarra and said she would do anything to live in a house with fancy curtains. “And what about you?” she asked.

“I’d like to work in a uniform,” I replied.

“Here,” she said, picking a yellow button from the footpath. “This is my good luck charm for you.”

We were thirsty, and our search for beer took us on totally divergent paths. When I came out of an alley where I had been trying to convince an old guy, who looked like he was auditioning for Frankenstein, that I was a virgin, my friend with the broken teeth was lying unconscious at the Shell petrol station, the one opposite Academic & General, and an ambulance officer was bending over her. I ran to her side. “Do you know her?” the ambulance man said.

“Yes,” I replied. “You could say that she’s all I’ve got.” I rubbed the yellow button between my thumb and forefinger.

In the ambulance I held her hand, and in the hospital watched her die through a glass window. Her folk found me sobbing into a polystyrene cup of tea. They gave me a place to stay and some new clothes, all of which were crucial to finding a job as laboratory technician. The job-search worker told me I would receive a cheque to cover travelling expenses and gave me an address that was out of town—a company called Xtra. My new-found benefactors were really happy for me; they said it was a fine position with long-term benefits.

~

On my first day at the factory, I met wonderful people. It was a bit warm, but I was glad to get out of the cold smoggy city. An armless woman was eating buttons of what looked like chocolate, using dexterous movements of her feet. She held each button between her toes and nibbled. She handed me one, and I popped it into my mouth. “What a lovely flavour,” I said, and asked where she was from.

“It is not where we are from, but where we are going, that is important,” she said.

“Could you help me understand Xtra?”

The woman asked why I needed to know.

“Because I want to be a good worker,” I said.

My co-workers gathered around me and asked if I would like an injection. It was kind of them, but I wanted to go slowly, to give myself time to adjust to this new environment. My supervisor nodded approvingly.

As I was getting ready for bed in a dormitory that I shared with a good number of strong-looking women, I found myself thinking that the yellow button had brought me a lot of luck. Moths fluttered against the large windows as I relaxed into my pillow.

Over the months, I found that my dreams had a recurrent theme. I was back in the city, married to a strange cold man, and looking after children who yelled at me in loud voices. Bring me this or bring me that, they said; or find me this or find me that; or I’ll die without this or that. I tried to sing them the songs that I was learning in my new job, we live in a lucky country ho ho ho, but they seemed unable to hear.

Girija Tropp is a winner of the Boston Review Prize and the Josephine Ulrick Literature Award 2006. She has been published in AGNI, Best Australian Stories 2005 and 2006, Fiction International, Mississippi Review, Denver Quarterly, and other magazines. Her Twitter handle is @girijawrites. (updated 11/2013)