Lia Purpura, Wasp Nest (detail), featured in AGNI 102

A Picture From Ireland

An incubus was tormenting my grandmother Odede in her sleep once again. Her screaming woke me up. I made for where she lay on her raised mud bed and tried to rouse her by shaking her to consciousness. This was the only way to rescue her from the chokehold of the incubus which she claimed pressed her down in her sleep, trying to kill her. She would wake up and blame her enemies.

When she eventually woke, her first words were, “We are going to Afuda village after the first cock crow in the morning.” This could mean only one thing—it had not been the usual incubus. Only bad nightmares made us go to Afuda village to consult Oboh Epadinpadin Oke, the most powerful native doctor in Esanland. She did not have to elaborate; I had followed her on numerous occasions to the smelly house that served as both shrine and home to the native doctor. My school friends knew that I followed my grandmother to consult the oracles and they poked fun at me. They called me a bat who is neither a bird nor an animal—a good Catholic and a juju boy. Their words did not bother me. I had to help my Odede. Ever since I was a boy, it had been my duty to be her “little man” and follow her wherever she went. As soon as my Odede realized that I could take notes in English and translate to our native language of Esan, I became her akonwe.

I was also my sightless Odede’s eyes to the world. The journey to Afuda was far and always strenuous, especially for a woman of her age. I once asked her after a particularly strenuous trip, “Odede, are there are no native doctors in our village, why do we always have to go to Afuda?”

“The ones in our village cannot see beyond their noses anymore, they are too hungry and lie about what they did not see,” she replied. Also what Odede did not say was that most of the native doctors had become Catholics and wore scapulas and rosaries under their agbada instead of the customary aban which gave them power to speak to the ancestors. Needless to say, my Odede did not like our parish priest Father Kelly, whose work it was to convert the old men and asked them to do away with “dead gods.”

When the old cockerel first flapped its wings, I removed my overnight loincloth and put on my khaki trousers and a checkered shirt. I pulled a foolscap sheet from the middle of my math notebook and tucked a pen in my shirt pocket. I helped Odede select a clean wrapper among many hanging from a rope behind the inner door. Then, while it was still dark, we set out. A few distant owls could still be heard hooting. I did a sign of the cross as we walked past the fading signboard of St. Joseph Catholic Church. After Father Kelly’s death, many villagers claimed they’d seen his ghost taking a leisurely walk with his hands folded behind his back and his cassock flapping. I looked away as we passed the churchyard; I did not want to see the ghost of the first white man to be buried by the village church. But I couldn’t stop imagining things, and when I heard nocturnal animals scavenging near our dark path, I tightened my grip on my grandmother’s hand.

As we descended the Okenidido hill, just two miles from our destination, I felt a rush of warm air. I tensed and did another sign of the cross (our catechist, Mr. Michael, told us that when we sense danger we should do a sign of the cross—In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, amen). Feeling the sudden tightening of my grip, Odede broke into a soothing song to take my mind away from fear. That was my grandmother, always trying to protect me every way she could. But I knew there was something wrong with such sudden warmth in the air; my mother had told me it meant that bloodsucking witches and wizards were dispersing from their otherworldly meetings. I recalled Father Kelly raising the chalice during Sunday Mass, this is his blood—drink and be…and I stepped gingerly.

We got to the native doctor’s house while morning was still hazy and farmers were getting ready for the fields. Odede told me to push open the bamboo door. It was not locked—no thief in his right mind would try to break into Oboh Epadinpadin Oke’s house in Afuda. The native doctor’s dog stood before us as the door opened, wagging its flea-ridden tail and yapping, then quieted abruptly and sniffed my dust-coated feet—its smell was stronger than a fishmeal fart. As I helped Odede sit on a carved wooden stool, Oboh Epadinpadin Oke emerged from his inner chamber and greeted us familiarly. He lowered himself to the straw mat on the floor. Lying in front of him were strings of Ogwega cowries, his instruments of magic, covered in dry blood.

“How are the children and your wives?” Odede asked, resting her walking stick on the bare earthen floor.

“The gods are keeping them from harm’s way, what can we humans that have only two eyes do?” Oboh replied as he shooed his dog away. He put white chalk on his tongue and, looking at the ceiling, which was full of holes, mumble-chanted words we couldn’t hear.

**

** 2.

Oboh Epadinpadin Oke was an ugly old man with a wrinkled face that looked like a squeezed rag; his hair had gone cotton white. The red skirt he wore was bedecked with cowries, juju amulets, and small carvings of ivory and bronze. A miniature talisman hung round his long neck and the rest of his black body was covered with white chalk. I wondered if he had slept like that.

Odede dropped her two-naira consultation fee on top of his Ogwega, as was customary. Back in the day, it used to be cowries, according to her, until the white man introduced paper and coin money. Oboh Epadinpadin Oke crumpled the money and touched his furrowed forehead with the dirty notes, mumbling prayers and incantations as he blessed his first earning of the day. I was afraid of the native doctor, but I found his incantations, prayers, and parables fascinating, similar to Father Kelly’s homilies and prayers in the church on Sundays, although when Father Kelly broke into Latin he completely confused all the villagers, who could barely even speak a word of English. I enjoyed listening to Oboh Epadinpadin Oke talk to the gods and ancestors (my father was now an ancestor, killed during the war) in a voice filled with praises. The native doctor spat heavily on the strings of cowries and began his quest. Closing his eyes, he seemed to be listening to a distant message. Odede had not yet told him the reason for our visit. I was waiting patiently; I really wanted to know what she’d seen in her dreams that made her scream and sweat. The native doctor broke into a song, rose gingerly from the mat, and retrieved his okede, a double-headed drum made from a boa constrictor’s skin:

I must return from my journey

The arrow never gets lost in its errand

I will return with a message from the gods

I must return from my journey.

Finally he gave Odede a tiny object that looked like a parrot’s beak. When she put it close to her mouth and spoke into it—”Please find out if it is well with my son in the white man’s land” —she was loud enough for the native doctor to hear.

So the dream had to do with my Uncle Sunday, who now lived in Dublin, in a country called Ireland. I liked their stamps because they were more beautiful than our own. I wondered what could possibly have happened to Uncle Sunday in my grandmother’s dream, or were there enemies in Ireland too?

**

** 3.

Uncle Sunday was Odede’s only surviving son. After finishing grammar school, he had decided he was going to be a catechist. This was on the advice of young Father McGee, the resident Catholic priest of the grammar school—Annunciation Catholic College—who said my uncle was the best altar boy he had ever worked with. Like the white priests, catechists were treated as gods in my village, respected, feared, and worshipped. And it was a thing of wonder that sometimes Father McGee allowed Uncle Sunday to put the white sacrament on our tongues—Body of Christ, amen. I heard that old Father Kelly frowned on such things as allowing a man who was not ordained and had no certificate from the Pope to administer the holy sacrament. Old Father Kelly took everything very seriously. He’d even slapped a boy on our baptism day for not lowering his head far enough for the holy water to soak all his hair; “You want to remain a heathen forever?” he screamed as he baptized the boy with a second strong slap. Everybody was shaking that day. Another reason my grandmother was suspicious of the priests was that she could not understand why these grown men wouldn’t marry. “How is the world supposed to continue?” she’d say. “You better not tell me you are going to be Ifada,” she would rant at my uncle, who liked to bring Father McGee to our house for a meal of pounded yam and egusi soup during Christmas. Since catechists were permitted to marry, Odede was less worried. She would have caught fire if Uncle Sunday had decided to be a reverend father. Me, I was just happy that a white reverend father was my uncle’s best friend and would find us HOLY enough to come spend Christmas Day in our house. And Father McGee had a sweet smell that was hard to forget, like my mother’s vanilla Nku cream.

When I was in primary three, Uncle Sunday left the country with Father McGee for “further ecumenical training” (I’ve forgotten to check my Michael West dictionary for the meaning of ECUMENICAL). Since then, he had not set his foot in the country again. He wrote Odede regularly, singing praises and saying wonderful things about Irish hospitality and Father McGee. Also he would tell us how Mass in Ireland was different from our own and that parishioners hardly brought goats and sheep during Church Harvest like we did in our village. But Odede just wanted Uncle Sunday to come back and marry a nice home girl. “God that created heaven and earth, when will my son come home to marry a good fertile girl so I can carry another grandchild before I die?”

**

** 4.

When Oboh Epadinpadin Oke took the bird’s beak from Odede, I readied my pen and paper to write down the prophecy of the gods as revealed to the native doctor. The old man was the privileged middleman between the gods, my grandmother, and Uncle Sunday in faraway Ireland. He started his consultation in an undulating voice; he spoke very fast with his eyes all white without the black spot:

Wake up . . . Wake up, Ogwega

A leopard with a cub never sleeps deep

The moon never sleeps with its eyes closed

The animal that walks behind an antelope eats leaves

But the animal that walks behind the lion eats the antelope

Wake up, Ogwega…Wake up and open your mouth

The parrot does not know how to keep a secret

Tell me what you see

Pregnancy is not a stranger to a woman’s womb

What else can count the teeth, if not the tongue?

Ogwega, tell me what you see

The eagle’s roving eyes miss nothing in the forest

No tree is too tall for a climbing monkey

No tree struggles with Akwobisi, except it’s suicidal

Look at this old woman sitting before you and tell me if her son is well or not!

“What is your son’s name?” the native doctor asked without looking up from his oracular cowries.

“Sunday,” Odede replied immediately, but she kept staring at the opposite wall.

Oboh Epadinpadin Oke went back into his trance and uttered more incantations. He wove in and out between our world and the spirit world.

Good or bad, our ears are ready . . .

Ogwega, wake up!

Oboh Epadinpadin Oke threw the Ogwega in the air and it landed farther away than he intended. He dragged it closer to him with his bony fingers, then gazed at the formations of the cowries and read the signs. All the cowries lay face down, every single one of them. Having followed my Odede long enough, I knew this meant something serious—like death. The native doctor’s face twitched furiously and his mouth contorted, it was not a good sign for sure, the cowries were not supposed to all lie face down. Not satisfied yet with what he saw, he threw the cowries into the air higher than before and again they landed like a squirrel shot down from a tree. He continued his intense conversation with Ogwega_._ He laughed mockingly. His laughter was like that of Father Kelly jeering at those that would go to hellfire if they did not give up their dead gods and give their lives to his living God. Anger welled up in Oboh Epadinpadin Oke’s old voice.

Do not lie to me, Ogwega . . . Do not lie

A man cannot become a woman and a woman cannot become a man

Do not be confused, the mother cow does not breastfeed the piglets

Does the lioness breastfeed the goat’s kid?

Tell me what you see in the whiteman’s land

Ogwega, tell me what you see!

He yelled and then stopped abruptly to observe the formation of the cowries. Confusion doubled his wrinkles. He stood up and walked in a dazed manner round and round the small consultation room. Bent with age, he dragged his left foot like a curse. The old man then danced a brief crooked dance and looked up to the cracks in his ceiling. Rolling his eyeballs until only the whites showed, Oboh Epadinpadin Oke finally sat down again. The dog came in from the back door and kept its distance, sniffing at bottles of charms and amulets in a corner of the shrine. The native doctor’s entire family was now awake; voices of women and children floated in from the backyard.

He looked straight at Odede’s tense face and said: “Odd things are happening in the whiteman’s land. It is a confused day. Ogwega says it sees two strange-colored moons in one sky, pink like a freshly scraped tongue. I have never heard this before. The two moons have fused together and are daring the sun to rise and drive them from the sky. These are strange times, old woman, something strange must be happening in the whiteman’s land which Ogwega cannot explain to me.”

Odede spoke fast, losing the usual gentleness in her voice. “Ask Ogwega what we could do to stop this strange thing from happening.”

We waited while the native doctor methodically gathered his Ogwega, like my chemistry teacher cleaning up after a failed experiment with our old Bunsen burner, kettles, and leaves.

**

** 5.

Long after Father McGee left the country, Odede still wondered aloud why white men would decide to live in an interior village like ours, a village without basic amenities like electricity or clean water. A village cut off from the rest of the world during the raining season. A village which Father Kelly used to say “the government did not take into consideration in the realm of things—therefore the parish must do something to make sure the church and school do not fold up.”

Father McGee’s old blue Volkswagen beetle had folded up under the frangipani tree at Annunciation Catholic College; it had become a plaything for schoolchildren and lizards. I remember when it was new and shiny and we would look at our dusty faces in the side mirrors. My uncle had been the only student allowed to drive it, something I never forgot to remind my friends. People said the young reverend father abandoned the car and the country because he could not bear the country’s decay anymore. After one last bloody military coup he left, but we also heard he had been quarreling with old Father Kelly—about what, we did not really know. Anyway, he helped my young uncle to escape the “decaying” country to Ireland and I became the only boy in school whose uncle lived in the white man’s country and that was all that mattered to me.

**

** 6.

As Oboh Epadinpadin Oke gave Odede instructions and told her what sacrifices would be needed to prevent bad things from happening, I wrote it all down.

“When you get home take a white cock and a black hen, tie them together with thread, and let them loose the next day. Sacrifice the birds in the middle of your husband’s compound. Tell the gods that your son in the whiteman’s land has no tongue for strange songs and should not be yoked with bareness. That is all I can tell you, old woman,” he said.

With that, the native doctor packed his Ogwega inside a gourd. The dog, which had fallen asleep by the shrine, woke up and stretched with a short bark. Odede thanked Oboh Epadinpadin Oke and I took her hand for the journey back home.

“Eziki”—her pronunciation of Isaac, my name—”did you write down what he said?”

“Yes, Odede. Let us go.”

I could have remembered what the native doctor said even if I had not taken notes. But Father Kelly always told us to write everything down because the dullest pencil is sharper than the sharpest brain. Written words never lose their memory; that was Father Kelly for you, a strange old Irish man who had stayed so long in our parish that he would mix white people’s parables with our own, the same way he mixed Guinness stout with local palm wine on Sunday evenings.

The walk home was quiet, except for some women returning from market who disturbed our silent thoughts with their greetings. My Odede replied to them briskly, hiding her worries. Her voice was not strained anymore, but I knew she was scared about what Oboh Epadinpadin Oke had told her.

Could Uncle Sunday be sick or in some kind of trouble? Was it not to avoid trouble that he had left with Father McGee? What strange thing had showed its face in the native doctor’s divination? Two moons in one sky? I wondered all the way home. The only thing I remembered our physics teacher talking about was an eclipse of the sun, a midday darkness we viewed in a bucket full of water. Our teacher said the moon has no light of its own but shines by sunlight reflected from its surface—but none of us believed that the moonlight we played by in the night was actually sun. Anyway I knew my Odede would not waste time in preparing the sacrifice prescribed by the oracle.

By the time we arrived in my village the sun was getting very hot. Villagers were moving about for the day’s food and some of my schoolmates were on their way to the farm already. Down the narrow path before a bend to our house, a man called Mr. Takwa walked aimlessly toward us. He never went to farm, nor attended village meetings. He was the joke of the village, a drunk. Sometimes he would piss in public, even when married women were around. Odede had warned me not to join the other boys in laughing at him, especially when he pissed on himself. It was not his fault, she said—the enemies had seized his brains really good. But she also instructed me not to listen to Mr. Takwa’s tall tales, which were usually about how the civil war had claimed the lives of his playmates, including my father. As we reached him, Mr. Takwa greeted Odede, and I greeted him, and he moved on with his characteristic limp.

**

** 7.

Entering Odede’s room I noticed a familiar brown envelope on her mud bed. My mother had collected the letter from the postmaster on her way from morning mass. Right away my tiredness vanished and my heart raced. I knew the letter was from Uncle Sunday—the stamps were unmistakable and very beautiful. I already had thirty-two of them peeled from the envelopes he used. My favorites were the colorful Christmas ones with the infant Jesus on Virgin Mother’s lap, also the 1977 ones with the entire Jesus family and their sheep, and the ones with EUROPA or NOLLAIG written on them.

“Look, Odede, Uncle Sunday has written you.” She raised her unseeing eyes suspiciously, as if she thought I was joking. We had not even had time to perform the sacrifice and now I was talking about a letter from Uncle Sunday. She stood in one spot as if afraid to move.

“Sit down so I can read it to you.”

Odede adjusted her wrapper, sat down with a moan of old age, and asked me to fetch her some drinking water first. As she drank, I watched her face and saw the stress of the long journey on it. Worries about her son had pulled her skin tight. After a couple of gulps from the aluminum cup, she asked me to read the letter. I opened the envelope gently, careful not to ruin the stamps, and got the letter out. Uncle Sunday always used a yellow writing pad. It was longer than the blue writing pads sold at Emos Provisions Store. Emos the storeowner once joked that our country had yellow fever, not yellow pads, and since then I never asked the big-bellied fool for a yellow writing pad when we replied to my uncle.

I started reading to my Odede, translating from English to our vernacular. It was a short letter, considering that Uncle Sunday usually wrote up to five pages explaining the weather, food, ways of living, and the things he was doing with Father McGee in Ireland. Maybe he’d written it in a hurry and would follow with a long letter soon, although his letters had not been as regular recently as when he first left the village.

Dear Mother,

Greetings in the name of Calvary, I Hope all is well and you are doing alright with health? How is Isaac and the mother?

_ I am doing fine and getting ready for Christmas, despite the cold here that is worse than harmattan.

Mama, I have an important thing to tell you.

My breathing was fast and shallow as if I had been running.

I would have even come home this Christmas to personally tell you the good news instead of this letter, but my hands are full at the moment. I know how important it is to you for me to come home and get married, there is no letter I have received from you since I left home that doesn’t mention it. I must tell you mama, things are different here and a lot easier than they are back home and I have decided to make my home with the one I love in Ireland._

I looked up from the letter to see if my grandmother was smiling at the news. Finally, Uncle Sunday had decided to marry! But she kept a calm face, waiting for me to read the entire letter, so I continued.

There is nothing I would not do to make you happy, but the will of God is very strong in my life right now and that makes me excited. I hope you understand me, since I cannot go against God’s destiny in my life I have decided to settle down with Father McGee. _

I translated for my Odede before I stopped. I was confused now, what did my uncle mean by this? Did Father McGee have a sister we did not know about?

“Eziki, is that the entire message Sunday has for his old mother?” My grandmother’s voice became weak as if she was suffering from malaria fever. She had sounded like that when she grieved over my dead father. I was afraid to read the remaining words I was now looking at. Something about them seemed wrong, but I could not lie to my blind grandmother.

“No, Odede, there is more.” I started translating the rest of the letter and noticed from the corner of my eye that she had started shaking.

This might be hard for you to understand but what I am trying to tell you mama is that I have finally decided to settle down with the one I love, a partner that makes me complete. Someone who has never been selfish and cares a lot about how I feel, no matter the difficulty. _

I stopped here and waited.

“Continue,” said my grandmother.

I am yet to meet a more beautiful person in my life. So I am very happy, and I want you to be happy for me. I have enclosed a picture here for you. We will try and visit when time and circumstance permit. Greet everybody for me and don’t worry about me mama, I am doing well.

_ Your son,

Sunday.

“Odede that is all,” I said and folded the letter.

My grandmother yelped, put both her hands on her head as if protecting it from a descending blow. I was waiting for her to say something but her face tightened, and her mouth opened slightly, revealing her tobacco-blackened teeth. I knew my grandmother well and I could tell she was not happy at the news I had just read to her. I had heard her morning and night prayers and knew that she wanted her son to return one day and marry a girl from our village. A wife who would speak the same language that she would understand. Someone like my mother who had been taking care of us since my father died, despite her moods. But now that he’d found someone far away, Odede’s face was like a clouded sky during raining season.

I tore the envelope, eager to retrieve the picture. I wanted to see a beautiful woman for my uncle and even more for my grandmother’s happiness. Black or white, it did not really matter anymore. Anything to give my grandmother some relief.

Odede still hadn’t said a word. Her legs were shaking, knocking her knees together violently.

I shook loose the small colored picture from the envelope. There, staring at me, were Uncle Sunday and Father McGee sitting together on a red settee in what looked like a parlor. My uncle was laughing while the priest had a small smile on his face. This was not the picture I was looking for, so I ripped the edge of the envelope, not caring about the stamps, to see if there was another picture hidden inside. But there was nothing. I flipped the single picture over and saw the inscription in my uncle’s neat handwriting: “Patrick and I.” Patrick? And Father McGee wasn’t even wearing his usual reverend-father uniform. Strange things are happening in the white man’s land, as the oracle had said. I held the picture close to my eyes as if there was something more to see, but it was only my uncle and Father McGee who stared back, happily laughing and smiling. I looked up and saw Odede’s blind milky eyeballs fixed on me.

“Odede, the photo does not have Sunday’s wife on it. It is only him and Father McGee. When we reply we will tell him to send us more pictures.” I did not know what else to say.

Odede stopped shaking suddenly, stood up without her walking stick, and adjusted her wrapper before staggering into the wall opposite the mud bed. It was as if she was drunk. I called her name as if waking her from an incubus attack, but she ignored me and kept trying to walk through the wall, where one of Uncle Sunday’s old pictures was hanging.

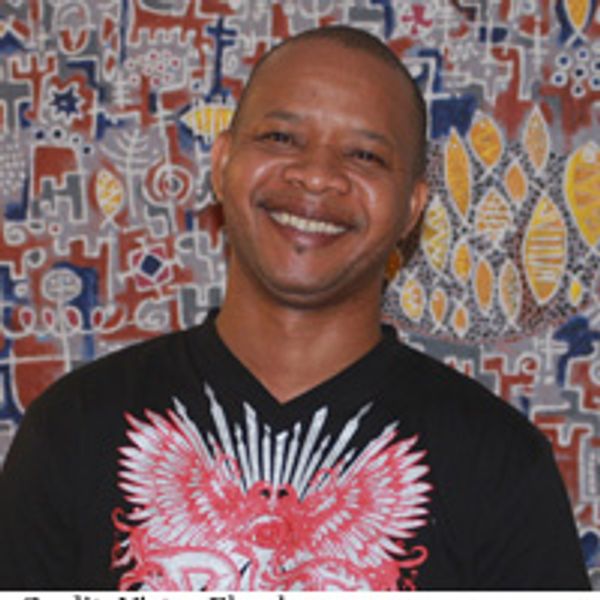

Victor E. Ehikhamenor

Victor E. Ehikhamenor was born in Nigeria. His fiction and nonfiction have appeared or are forthcoming in The Washington Post, Wasafiri, The Literary Magazine, Per Contra, and elsewhere. He is also a painter and photographer whose art has been widely exhibited, collected worldwide, and used for notable book and journal covers, including Chimamanda Adichie’s Purple Hibiscus, Helon Habila’s Measuring Times, Jonathan Luckett’s Feeding Frenzy, Unoma N. Azuah’s Sky-high Flames, and Dreams, Miracles and Jazz: New Adventures in African Writing, edited by Helon Habila and Kadija Sesay. Ehikhamenor holds an MS in technology management from University of Maryland, University College, and an MFA in fiction from University of Maryland, College Park. He is creative director of the Lagos-based newspaper NEXT and 234next.com. (updated 10/2010)