Lia Purpura, Skate’s Egg Case (detail), featured in AGNI 102

So Long, Studs

November 20, 2008

One night, about twenty-five years ago, Studs, coming home from downtown, was mugged in front of his house. “Watch and wallet,” demanded the mugger as he wrestled the little guy on the grass. “Okay,” huffed Studs. “Lemme get’m. Is this your first job tonight?” “What! Gimme the goddamn wallet.” “I’m gettin’ it,” said Studs. “What’s your usual take on a job?” “What the hell you sayin’? Gimme the fuckin’ wallet.” “Right-o,” said Studs. “But when did you start doin’ these jobs.” Bewildered by this verbal mugging, the thief paused and was hit with more questions.

On the ground, surrendering his wallet, Studs Terkel was doing his job as the mugger was doing his.

It is now twenty-one days since Studs died, and it’s clear from the tributes to him that much of the reading country realizes it has lost a great man. A few days after his death, the country elected another man who many felt had the ingredients of greatness in him. Like Studs, Barack Obama gives voice to many who’d been silent or silenced. These two Chicagoans are part of that Chicago tradition of expressing the needs, aspirations, and life of unexpressed America: Mrs. Kinzie’s Wau-bun, Hamlin Garlin, Dreiser, Farrell, Algren, Bellow, ten or fifteen others.

Back in the Fifties, I didn’t think much of Studs. A culture snob, I didn’t think much of Brahms and delighted in such mots as Stravinsky’s “Wagner is the Puccini of music.” I championed such writers as J. F. Powers, Peter Taylor, and the Bellow of Seize the Day (Augie March seemed back then too loose-jointed for me), along with Proust, Joyce, and what Ezra Pound called “the Rooshans.” So Studs, who daily “interrupted” the music on WFMT, was for me a bowl of mush. Once, he came up to a round-table discussion at the University of Chicago, and I thought I’d never heard a gabber who couldn’t locate a verb to pin down his adverbial clauses.

Every now and then, though, before I turned the dial, I caught a few Studs remarks whose acuity and knowledge surprised me, and I’d stick with that day’s interview. When Golk, my first novel, came out in 1960, I went down to the old WFMT studio and was interviewed by him. Another surprise. Studs’s copy of the book was filled with underlined passages. It was soon clear that he’d not only read it carefully, he had ideas about it. They weren’t my ideas, but when I disagreed with them, he used them as levers to push me to places I hadn’t seen. Of the twenty-odd interviews I did, this was the best, and the interviewer, despite a few sentimental intrusions, was not making himself the center of the hour. A modest ringmaster, he kept the book and its author under the spotlight.

Over the years, I’d see Studs at book events and funerals, and as fellow commentators on Nixon’s resignation and the Rushdie fatwa. By this time, I appreciated his wry intelligence. We were fellow Chicago boosters and, from our different sides of that street, appreciated the difference.

When Studs’s first book, Division Street: America, came out, I reviewed it in one of his favorite magazines, The Nation. “For most of history,” I wrote, “the ordinary man’s interior was a tundra of silence. In the eighteenth century, autobiographers and novelists began making the maps by which the mute Jean Jacques’ and Myshkins discovered where and what they were. . . . In our century, popular analysis enables every man to see himself as a complex, fluent character. . . . Self-analysis has become self-revelation.” I compared Studs’s excavations of these self-revelations with those of the anthropologist Oscar Lewis and the Italian social reformer Danilo Dolci. Such authors “aren’t Chaucers but they are Harry Baileys.” Studs called. “Who’s Harry Bailey?” I said that he was the innkeeper host of the Canterbury pilgrims, the one who encouraged them to tell their tales. “I like that,” said Studs.

We did three or four more interviews, the last about ten years ago. By then, Studs was deep in his eighties, but he was not only as good as he’d been forty years earlier, he was better, more grammatical, more precise, more graceful, even more generous with his guests. There the book was in back of his mike, underlined as heavily as ever. As prelude, there was a piece of music that played a part in the book.

He was going deaf: “No hearing at all in the right ear.” His walking was slower, the shock of hair grayer, but the generosity, decency, and curiosity were there with a sauce of sharpness, wit, and nostalgia. He loved to elaborate your memories with his. Talking of the day FDR died, he remembered walking along streets where every car and house radio played the same account. “You didn’t lose a word.”

We said goodbye, I feeling it might be the last time, Studs sensing my feeling but knowing, rightly, that there were years left.

There were. The last talk we had was in 2005 while we ate lunch before reading at different stalls of the Chicago Literary Festival. Studs took seconds to remember who I was and, recalling my friendship with another Chicago-lover-creator, the recently dead Saul Bellow, talked about him. He was alert and sharp. If he didn’t hear, you didn’t know, because he either sensed what you were saying or read lips. “Take it easy, Dick,” he said as he went off with a guide to his stall.

You too, Studs. I wish you could have lived a few more days for the results of the election which, like so much else in the world, absorbed you, but All Saints’ Day seems to me the right day for you to have taken off.

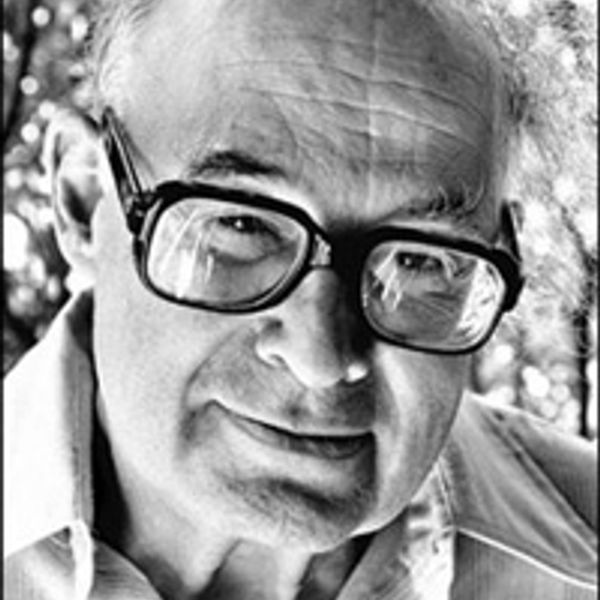

Richard Stern

Richard Stern (1928–2013) was an American writer and educator. His novels include Pacific Tremors (2001), Europe, or Up and Down with Baggish and Schreiber (1961), Golk (1960), Stitch (1965), and Natural Shocks (1978). His collected stories, Almonds to Zhoof, appeared in 2005. In 1985, he received the Medal of Merit for the Novel, awarded every six years by the American Academy of Arts and Letters.