Lia Purpura, Wasp Nest (detail), featured in AGNI 102

Parthena Earns Her Name

Everybody knew Parthena because she did it with everybody. The (most innocent boys, the most pure girls, the men like Maheri the knife-sharpener, Rapti the tailor and Brountzo the bronzeware man, even her aunt Erophili who stopped by once a month with magazines from Patras. Nearly everybody except her father had lain on top of her, what’s a man to do? Last Easter, her mother held an ax over her daughter’s head for an hour while she slept but couldn’t find the strength to use it; she did find the gumption to pour horse poison into her rice pudding the very next morning. Parthena survived, crawling under her bed, coughing and spitting for three days and nights until she recovered.

A week after her fourteenth birthday, Parthena’s mother drowned while trying to save Kiriako, their pet goat, who had fallen into a stream swollen from the spring rains. Parthena held the goat by the chin and sang in a lilting gentle voice, “What will become of orphan me, with my thing no bigger than a seed, what will become of poor me, everybody’s filling me with his bird,” and then, in front of her three brothers, cut its throat with a butcher knife. The goat buckled, gurgled blood, and fell onto the marble floor, legs splaying out like a broken doll. Parthena dragged the goat out of the home, down the path and threw it into the stream, watching the fresh carcass bobble along the surface, then she returned and wiped up the blood with one of her mother’s old skirts. When she was done she burned the skirt and the rest of her mother’s clothes inside an old barrel full of dirt and chicken droppings and a grey cloud passed quickly over the village smelling of cloth, dung, and, some said, bits of her mother’s black soul.

The village priest performed the funeral ceremonies in the mountain Church of Saint NouBrios, a church so old the stones smelled of frankincense and sour wine. Parthena stood at the head of the casket, above her mother’s pale face. While the priest intoned the ceremony, a large horsefly wandered into the cool dark church and quickly made its way to the body. Parthena swung at it, clapped at it, and tried valiantly to scare it away but when the fly finally landed on her mother’s cheek, Parthena pounced on it with a resounding “swack,” and squished it against her mother’s face. She quickly scraped the fly off her mother’s skin, noticing that her mot her’s flesh bounced in a strange loose way as if it was already slipping off her bones.

“Step away!” hissed her oldest brother. Her father, bent and bowed, noticed nothing at all. When the priest lifted his arms, his magnificent golden stole fluttered and glinted in the candle light and Parthena recalled his bed and his long white beard that was worse than a scratchy wool blanket against her soft skin.

After her mother’s death, Parthena seemed to have changed. She kept herself away from all men, prepared her family’s meals, collected twigs and small branches for the winter, and even cleaned her three brothers’ shoes at night. Neither Maheri nor Brountzo nor any passersby dared approach Parthena and she herself seemed to have grown pious and uninterested in anything below her skirt. Her three brothers decided that their mother’s death wasn’t in vain. Though it was too late to earn her name, Parthena might at least fool some stranger into marrying her, if she behaved herself long enough.

One morning, exactly forty-one days after her mother’s death, rather than draw water from the well like she did every dawn, Parthena went to the village square, wearing a loose black dress and a black scarf around her neck—she’d seen women tie their scarves like that in her aunt’s magazines.

She sat on the damp stone wall, leaned back on her palms and, directly across from the old men sipping coffee, hiked up her skirt and flapped her legs back and forth like butterfly wings, banging her knees together and exposing her flaming Acropolis for al1 to see. With grunts, coughs, whispers, and some serious spitting, the men stopped talking I and twirling their worry beads and turned in her direction. She crossed one leg over the other like a man, legs still wide enough to hug a barrel, and pretended to examine the brown dirt along the bottom of her shoe, shaking her head in disdain. Her hair, washed this very morning with crushed hyacinth and jasmine, glistened in the bright sun.

An old man with a black band around his sleeve got up from the group and shuffled over toward Parthena, all the while kneading and unkneading his knobbly fingers. Occasionally he looked back at the rest of them who had now turned their heads away—their heads mind you, not their eyes. He stood in front of her, coughed, swallowed, coughed again.

“Are you getting sick, father?” Parthena asked, lifting her leg to examine the sole of her other shoe.

“Have you no God? Your mother. . .and the day after the sarantakosti!” His jaw suddenly went crooked and he fell onto the small ledge, eyes creased in pain. The village priest appeared, black skirts flapping, and sprinkled water on her father’s temples while making the sign of the cross over Parthena’s legs, which were still wide apart. Isidoros the accountant showed up and rubbed some salve into her father’s neck while Jordan the choirboy took the priest’s bible and read it in a fast, excitable voice. The three brothers arrived. They huddled over their father, spoke to him, massaged his neck and clapped his back. He didn’t say a word, just sat there and stared up at the fig tree. Parthena fell to the ground, hugged his legs and kissed his shoes.

“Satan’s child!” her father said suddenly, kicking her out of his way like a snake. He stood and then keeled over like an empty husk. Parthena later recalled a brush of wind against her cheeks, as if a hand had passed over her face like a priest’s benediction, but she decided that this actually was the wind. It couldn’t have been her father’s soul escaping his body with a sudden exhalation because when he fell over he banged his nose on the ground and no soul would let its body do such a stupid thing, especially when the body in question had allowed its soul to sojourn there for upwards of seventy-five years.

The youngest brother, thirteen year-old Manolaki, hugged his father, then pulled off the black band and put it around his own left arm, the one closest to the heart. The priest muttered his Kyrie elayson, elayson eemas and told Parthena to return to her home and lock the door.

“Maybe it’s better this way,” the oldest brother said. “The old man doesn’t get to see what happens to Parthena.”

They finally found her just after sunset, hiding in the hills, crouching inside Douni’s hut, the half-crazy shepherd who tied his pants with string and danced naked on the snow in the winter. They took her to a tree behind the church, hung her up by her long hair and let her hang there for a couple of hours. She moaned and groaned, but when she dropped to the ground she scampered back to her house like a wounded cat. They locked her inside and put her youngest brother in charge.

The following morning, while Manolaki was guarding her, she took off all her clothes and washed herself in front of him, then brought his hand to her budding breasts and asked him to figure out which one was bigger and which smaller. He rubbed and squeezed and checked and re-checked and finally he fell upon her with a loud yell, like a happy puppy. The next day they went to the chicken coop. Nobody would think of looking for them there. From under the tangle of limbs Parthena tried to shoo away a chicken that had commenced pecking Manolaki’s white butt, but when the animal refused to obey, she grabbed it with both hands and broke its neck. Nobody would have known about all this if Manolaki hadn’t bragged to his older brothers that his sister had been obliged to kill the chicken for his sake.

The eldest brothers dragged her into the street that very morning. One tore off her skirts while the other one bound her with twine, tying each leg to a cart wheel and the arms to the wooden posts of a fence. Then, the oldest took a burning iron and brought it close to the mop between her legs.

“You see,” he shouted, “now you’ll want to keep your temple shut to all visitors!”

“Burn me, you bastard, burn me!” she shouted. “l’ll keep it open for all believers!” She spat at them, twisted her fingers, pulled at her hair and slithered on the ground, trying desperately to close her legs. Her cries brought the whole village into the street. Barba-Kosti and Maheri and Rapti stared and twitched their noses at the idea of hot flesh and sizzling hair.

Even though the iron didn’t actually touch her, it burned the inside of both her thighs and soon enough large pink welts and bilious boils; rose up. When they untied her Manolaki took her to the stream where she sat for the rest of the day, savoring the cool flow between her legs, coming out of the rushing water only for a few minutes to stop her teeth from chattering.

A few months later she was with child, her own brother’s. She hummed a special tune while gathering up sticks and steering sheep. This tune she’d heard her mother sing for cases such as hers.

My daughter gave birth to an ashen beast

like a snake with eight heads and eight eyes.

It bawled like a dog at a bloody feast

until a big stone crushed its cries.

Fat-Mary, aunt, midwife, and all-round village expert, told Parthena the preg-not herbs were no good this time, she was too far along. They waited for nine months to go by and then Fat-Mary delivered the baby. They wrapped it from head to foot in cloth so it would see neither sun nor life, then the brothers loaded the bundle onto their donkey’s back and took it to the top of the mountain. On the way up they searched out and for five drachmas found a godfather and a priest to baptize it, so the baby would land in God’s arms when it fell to the earth from the peak of Mastro-Vounio.

When the brothers returned it was Parthena’s turn. With the blood still fresh on her body they threw her over a donkey and passed a twine around her waist and the donkey’s wide belly so she wouldn’t slip off. Fat-Mary pulled her hair like Clytemnestra and shouted at them to wait at least a week so she could recover from the childbirth, but they told her to go fart dust. Parthena’s fresh blood spattered to the ground.

“Even if she is a whore,” Fat-Mary shouted, “she shouldn’t be hanging from a donkey!”

Maheri the knife-sharpener was the first to throw something at her—a fish—and he called her a shrofa, a “scrofulous dog” and Brountzo the bronzeware maker called her a tsoupi, a “dirty mop.” Parthena’s voice was muffled by her own luxurious hair and the rumble of deaf donkey hooves. Nonetheless, some heard her describe Maheri’s thing: a small, dead frog that dangled from between his legs. She called her brothers satans and lizards, not worth a single grain of wheat. Her oldest brother’s penis was splayed like an anchor and her middle brother’s was a long skinny worm no woman would ever enjoy. Her youngest brother, she said, was a bull of a man and she called on him to save her. She didn’t know they’d tied him up inside the house and pushed his index finger into burning embers, as a warning.

The villagers made a sort of corridor for the donkey to run along and slapped its hind when it passed by at a decent gallop. It ran hither and thither and left steaming manure in its path while Parthena bounced up and down and the twine cut into her flesh. Children shook crab shells stuffed with pebbles. Men and women threw stones, spoons, forks, a baby’s buttrags and handfuls of hard green olives. A girl flung a white cat at her. The cat sailed gracefully through the air, dug its claws into Parthena’s legs for balance, then leapt up a bougainvillea and sat on the edge of the roof, licking its paws, staring at the villagers.

Hands up to protect herself from the hail of flying objects, Fat-Mary ran alongside Parthena and shouted at the villagers to take pity on her, as Christ had taught. “I’ve read the bible!” she shouted, throwing down a rag she caught in mid-flight. Maheri too asked them to stop but since he had been the first to throw the fish—as well as a handful of the donkey’s own manure—they didn’t listen to him. He tried to grab the loose reins, but the donkey kicked in the air with its hind feet and broke a clay vase hanging from Koukli’s balcony. Red shards exploded in Maheri’s face, cutting his cheeks.

It took Douni the wild-man to stop it. Barefoot, in cut-off pants and a hat like a crown, he suddenly appeared in the donkey’s path and tinkled a tin can with a fork. In front of a such a strange apparition, the donkey slowed down. Douni grabbed its reins and pulled it to a halt with such strength he nearly forced it to kneel. Then he calmly set about untying Parthena from the donkey—which now found the opportunity to munch on a geranium sitting on a window sill—and hoisted her over his shoulder. Parthena’s heart fluttered against his chest like a small bird.

“If we see her again,” shouted the oldest brother, “we’ll pour a whole liter of snake-poison down her throat, law or no law! Take her away from here.” With the older brother’s blessing—strong as a legal document—Douni jogged out of the village and ran like a deer over the rough ground, leaping and hopping over rocks and small streams, skirting bushes, bending for low branches, vaulting over the stone walls that crisscrossed the hills, all the while muttering Kakoi anthropoi, bad people, kakoi.

Inside his thatched hut, which smelled not of mutton or goat but of basil and thyme, he laid Parthena gently down on his simple bed of dried leaves and hay, smeared yogurt over her stomach and sprinkled crushed clover over her wounds. From the cistern next to the maple tree, he brought a pail of water and washed her up and said kalo koritsi, good girl, good girl, trying hard not to squeeze her breasts as he did each morning to the goats. But Parthena was not a goat nor was she about to give milk, so with a sigh, he went about taking care of her cuts and lacerations.

He didn’t need to go far for food. He had his own supply of milk, cheese, eggs and mutton. He did a water-dance each day on the shiny earth in front of his hut, pattering about in his bare feet and singing something that sounded like a speech put into melodies. When Parthena was well enough to talk—Fat-Mary had been by to see her every day—he told her they wouldn’t do it until they were married and he would respect her, but snakes as big as Hercules who had once lived in these very hills would surround her if she ever tried to run away. Parthena held her head low and nodded her humble agreement. Her face was dry and blistery at the corners of her mouth and a crust festered along the brow-ridge of her eye.

At night she would stare at the lights from her village, flickering through the wide cracks of the twig-door like fireflies. Her little brother, Manolaki, what was he doing? She did think she saw him once, standing next to the single olive tree, his hair sticking up like nails, his legs the usual atlas of bruises. She didn’t wave or call out. Better to forget. She did hope that when Manolaki heard the lonely hoot of the ghioni bird calling for its lost brother he would think of her.

With the help of two rugged cousins who lived in the mountains, Pentali and Pentouli, Douni built a small stone home that resembled a large sheep pen and moved her into that. One of them, Pentali, who was half-Albanian and had blonde hair and crooked white teeth, spoke to her kindly. She pretended not to hear him but whenever he was around she wore the dress torn from the donkey ride rather than the ankle-length one Douni had bought for her from the village.

Soon it was spring and the sun was so bright she had to collect shade in her palm to keep from squinting. During the day she counted and sorted the eggs into categories (hatchable, edible, and bad) while Douniand other shepherds tended the sheep. “Fhiou!” they shouted and whistled, “Phee! Phee! Back you blasted sheep! Back!” When she was done she’d sit on the earth and stare at the wild perdika that soared up Mastro-Vounio, raced along its steep, stony face and circled the peak. She imagined that from those heights the birds could see all the shepherds and all the flocks of Erymanthos, each mule and donkey, all the terraced hills, her village and all its villagers with their small white homes and pails of green basil, and sometimes, while hovering above, perhaps they spotted Parthena herself, sitting on the earth, sorting out the eggs.

Each night after darkness moved in with its full adult weight, Douni left his bed and lay down next to Parthena without touching her. His body was sinewy and hard, like an animal’s. Sometimes he held Georgia the chicken under his arm and slept with it. Other times he held large bits of wool in his fists.

Parthena often counted the stars, dividing them into bright, flickering, and lonely. When she was well enough she began to do things like gather up horto and glistrida and sprinkle them over dried bread soaked in olive oil. Sometimes she would crush a tomato and mix it up with feta cheese, dried bread, olive oil and oregano and serve it for dinner. Douni would grumble in appreciation. When chunks of food dropped from his mouth Parthena would pick them up and pop them back in.

They lived like that for nearly a whole year—eating greens, eggs, mutton and whatever else grew from the ground. Douni still didn’t touch her. She had seen him naked more than once, when he did his water dance, and knew that he was capable as a man and wondered what he would be like on the night of the wedding. On the Fifteenth of August, which was the Virgin’s day, Douni brought her a small icon from Patras, so she could celebrate her namesake, since Parthena meant “virgin.” This icon she hung up above the fireplace.

They were married in September with Fat-Mary as their only witness. Her oldest brother, believing she had finally changed her ways, told the priest to bless her, and sent her their mother’s jade necklace and promised Douni two hectares of land. Manolaki sent her a linen sheet and a small picture of himself which she put up next to the icon of the Virgin Mary. That very night she showed Douni what it meant to be in bed with her and their cries, they said, were heard all the way to Patras, over sixty kilometers away.

Very soon, rather too soon in fact, Parthena had a belly out to there, a woman on the verge. At night Fat-Mary collected the serniko-herb, so Parthena would give birth to a male, a shovel, as she called the boys, instead of a mop.

“That daughter of Penelope’s,” Fat-Mary would say while feeding her the herbs, “she has such a big mop between her legs, she could choke a man,” or, “Vassili’s son, well I’d rather lie with a battalion than go a single round with him.” She would come over right after Douni had slept with her and massage Parthena’s stomach and thighs while Parthena held her legs in the air, northbound.

If it’s his sex you want to produce, on a full moon let him

fill you with his juice;

if it’s the opposite you want, let him first lick your mop.

When Parthena gathered lemons close to the village, she covered up her face like a Turkish woman’s and never ventured into the village itself. Besides, all three brothers had moved to Patras. Sometimes the little boys would run past her and shout “Parthena! Parthena! All the men know Parthena!” She would smile at them with that way she had of hers, and they would stop shouting and calling names and wander about the fields and dream about her.

Within three months of the marriage, Parthena’s stomach was so large that Fat-Mary knew she was close to nine.

“What will you tell Douni?” Fat-Mary asked her. “He’ll stamp your head into the ground. He’ll fill your mouth with dirt, or worse, maybe he’ll send you back from where you came. The men are still waiting to see if you’re going to be a good wife or a bad woman.” Parthena looked at the white houses down in the valley. A sudden breeze caused her to shiver. “You still insist he didn’t touch you until after the wedding?” Parthena nodded her head and drew a lace shawl around her shoulders.

A week later Fat-Mary brought in her sister to help deliver the baby.

“Saint NouErios of Erymanthos, save her!” shouted Fat-Mary’s sister. “I’ll bring you forty heapings of hair and light candles for as long as I live.” Though Fat Mary’s sister wailed and cried, she nonetheless rubbed her hands in glee.

“I’ll go barefoot and drag myself across Greece to Saint Nicholas to baptize the child,” Parthena whispered hoarsely, lifting herself up on her bed, enough to see Douni kicking a large rock to bring some of her pain onto himself.

“Saint Liberation! Deliver us!” Fat-Mary said and with one scoop, brought up the child, a healthy squealing boy. Douni yelped with joy and did another dance, hobbling on one foot because of the kicking. But at dawn he left without saying a word. Parthena told Fat-Mary not to worry and to feed her baby proper food. They gave it pomegranate, wine, snake-horn, wasp, poisonous fish, and crab pincers. The pincers would give the baby strong teeth; fleas and mites were fed to keep them away when he was asleep. Donkey milk was for the whooping cough. But if the baby was doing fine, Douni wasn’t around to see. He had disappeared for a whole week now and Parthena stared out at the hills and every morning asked the two Albanian cousins if they’d seen him.

“But what will you tell him when he returns?” Fat-Mary said and tugged at her white hair. “What? And who is the father? Not that Pentali, the Albanian? Or was it his brother? You are a tsoupi aren’t you? Will you not learn?” Parthena only smiled, that coy smile she used on the boys when they called her names or when the men looked at her in that special way.

He did return, on a bleak Sunday afternoon, when the winter squalls brought dark brooding clouds above Mastro-Vounio. He came into the hut holding a live chicken, which squawked and clucked, and then he twisted its neck and threw it at her feet.

“Your brother was right,” Douni said, “you are a whore. Three months after our first night together you have a baby. The shepherds told me it’s two months for lambs, six for mares, and nine for people. Nine. I’m sending you back to your village, come what may.”

“No, my Douni,” Parthena said and moved the baby from her right to her left breast. The loose one spilled out over the half-done up buttons of her dress. “Sit down,” she said.

He picked up the chicken and cradled it in his lap. “Dumb Georgia,” he spoke to it, while staring at his wife’s loose breast. “So dumb.” Parthena laid the baby onto their bed and buttoned up her dress, slowly.

“Listen,” she began, a slight smile on her lips. “I’m good with numbers right? You know that.” Douni nodded his head. “I’ve been married three months, right?” She showed him three fingers. Douni nodded his head again and stroked the chicken’s feathers. “You’ve been married three months, right?” Again he nodded. She showed him three more fingers. “That makes six. And we’ve been married to each other for three months, right? Three plus six makes nine.” to each other all fingers save her left thumb. Douni tossed the chicken into a pail, smiled, went out, took off his clothes and danced in the sun. Below them the Corinthian Gulf glittered like crushed glass. Parthena plucked the feathers off the chicken and they had it for dinner.

With her baby strapped to her back, Parthena began to visit the old abandoned churches in the mountains, Saint Osios the Blessed and Saint Irene the Peaceful, cleaning them up with an old broom and lighting candles on their namesdays. From the village sometimes they saw her wedding along ancient paths, her youthful energetic stride full of purpose now, as she went from holy place.

She went to the churches for years and had three more children—all blonde and none of whom resembled Douni. Parthena outlived both her brothers and her husband and got to see electricity, water, and roads come to her village. She died in her chair, stiff and proud as a butterfly, while staring up at the birds hovering above the peak of Mastero-Vounio.

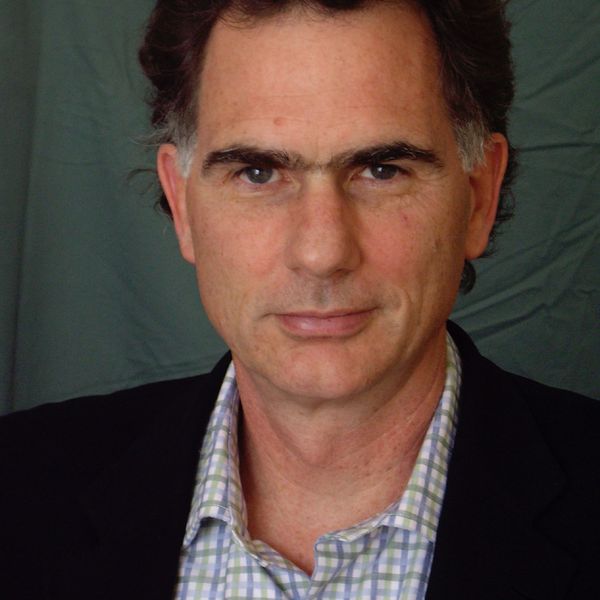

Nick Papandreou

Nick Papandreou’s most recent book, The Magical Path to the Acropolis (Melissa Publishers, 2016), is part of a series on creative modern Greeks. His essays and stories have appeared in The Antioch Review, Harvard Review, Indiana Review, AGNI, The Threepenny Review, and elsewhere. He writes in both Greek and English. (updated 10/2017)