Malak Mattar, Finding Peace (detail), 2020, oil on canvas

The Violence of Style, and the Impossible Pedagogies

To say the violence in “Style in Slow Motion” is based on a true story, while accurate, bores me to tears. Or, more accurately, to borrow a line from Tim O’Brien, it offends my inner ear. More importantly, admitting as much stultifies conversation, a bald fact for which I’m largely responsible.

“Style in Slow Motion” is one of the more successful poems (whatever that means) I’ve written. This is a fact that has had to be brought to my attention. It’s become a set closer whenever I give a reading. Friends and strangers have felt compelled to say things to me about that poem more than most I’ve written. But the comments are usually the same: “Did that really happen?” Or “You poor thing.” Or “Man, I would’ve blasted the bastards.”

I suppose the violence central to the poem’s surface conflict preoccupies its readers and listeners. I wrote the cursed and blessed thing, so that’s on me. And let the record show: I’m grateful for any reaction to anything I’ve written. But the preoccupation with the violent acts within the poem is—how can I put this politely—short-sighted, thin-skinned, and dunderheaded.

I don’t say these things. These kinds of thoughts morph into lesions on my soul, perhaps.

What I want to say to the kind-hearted, generous listener, and reader, is “You short-sighted, thin-skinned, dunderheaded jerk, it’s about the impossibility of teaching, specifically teaching style, which like vision, is entirely unteachable but is as necessary as water if a writer is going to earn his or her salt in this fucked up business of laying the soul on the line for peanuts. But you don’t care about that because you want easy answers. Have you read Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried? It’s clear you haven’t. I can see it in your eyes and posture. You’re too fucking happy. Look. There’s a little piece in it called ‘Good Form’. Seek it out. Get back to me in five years. If you’re still writing, we can talk.’”

If I were to say this, I’d never get another invitation to read anywhere again. I sure as hell wouldn’t invite me to read anywhere if I heard myself say this to some eager, young, good-intentioned writer. And if I heard a writer say this to some eager, young, good-intentioned writer, if it were a man, I might deck the prick. If it were a woman, I might consider finding her car and slashing her tires.

So, I usually keep quiet after my readings if I’m asked what have become the usual questions about “Style in Slow Motion.” But it is the poem about which I get the most questions.

What I don’t say is that the violence—true, OK?—in the poem is a diversion to get the reader or listener into the little, but necessary, world of the poem: the confusing cosmos of learning, even if the lesson is simply to shut up; or not so simply to speak up when one is terrified.

What I don’t say is that it’s a poem of hard lessons, maybe impossible ones.

What I don’t say is that I can talk about violence all goddamned day, and you’re not going to feel much; but, go to the store to buy some milk and get mugged: see, you’ve already got a better story. Go on now: tell it as only you can.

What I don’t say is not one person has ever asked about the dedication of the poem, which is, “to my students.”

What I don’t say is that no one’s ever asked about the epigraph, which is an entry for the word style in The Oxford English Dictionary. Style is essentially violent, just as violence is essentially stylish. Such flippage of syntax is also initially stylish, but finally violent because it really says nothing at all without anything concrete to back it up. See? I had you there for a second.

What I don’t say is “Don’t be cute or coy in your writing. It makes the soul grow old.”

What I don’t say is that no one’s ever asked about the form of “Style in Slow Motion,” loose as it may be: couplets hacked away into a verse kind of blank, elastically but not entirely chaotically iambic.

What I don’t say is that all I’ve got to say is white noise until you go feel it upon your pulses.

“But listen,” Tim O’Brien writes in “Good Form.” “Even that story is made up.” And a little bit later, his daughter (his real daughter?) asks “‘Daddy, tell the truth,’ Kathleen can say, ‘did you ever kill anybody?’ And I can say, honestly, ‘Of course not.’ Or I can say, honestly, ‘Yes.’”

I usually say thank you. If I don’t, that means something, too.

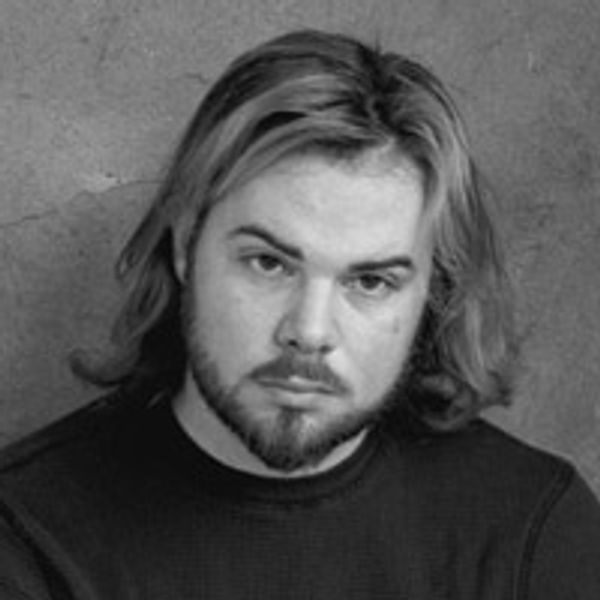

Alexander Long

Alexander Long is the author of three books of poems: Still Life (2011), which won the White Pine Press Poetry Prize; Vigil (New Issues Poetry & Prose, 2006); and Light Here, Light There (C & R Press, 2009). With Christopher Buckley, Long co-edited A Condition of the Spirit: the Life & Work of Larry Levis (Eastern Washington University Press, 2004). Long’s work has appeared in The American Poetry Review, American Writers (Charles Scribner’s Sons), Blackbird, Callaloo, Pleiades, AGNI, Quarterly West, The Southern Review, and elsewhere. He is associate professor of English at John Jay College, CUNY. (updated 1/2016)