Lia Purpura, Skate’s Egg Case (detail), featured in AGNI 102

Water Music

I awoke this morning to rain on the skylight and gypsy violin music running through my head. Wind and rain made music, along with the birds, before human beings achieved it, before there was such an idea or word as music. So close is the kinship between wind and rain and wind and music, that when a gale blows across our hillside acre here in Ireland, it catches under the eaves of the shed’s tin roof and blows so tunefully you’d swear someone was playing a flute out there.

As I was waking I could hear Grace in the kitchen, where she had gone to make tea, moving among the unaccustomed sounds of water. Water from our own faucets. First it coughed, then it stuttered, then it gushed and tumbled into the waiting kettle.

I say “unaccustomed.” Three days ago it had all dried up. But the force of a hurricane in the Caribbean blew a storm up the Gulf Stream and gave us a good soaking clear over on this side of the Atlantic. It brought the trauma of Hurricane Katrina to mind, and what that disaster had meant to the city of New Orleans. We live on the slopes of Sliabh na mBan, the Mountain of the Women, in County Tipperary, and we draw our water from a small reservoir further up the slope of the mountain. Four families organize their lives around the water from this source.

The ancient Greeks cherished their holy wells and paid obeisance to the local spirits who presided over them. Holy wells were a feature, too, of the spiritual life of the pre-Christian Irish. Even today you can come across a spring with its overhanging whitethorn tree, onto whose branches people will have tied bits of cloth and string which symbolise their prayers, hopes, and wishes.

Our reservoir has few associations with the sacred. I doubt many prayers have been uttered there. Last Christmas afternoon, with no better purpose than to walk off the effects of the turkey, we pulled on our boots and heavy coats and walked up to it across the fields through the horizontal rays of the thin December sunlight. We came to it across muddy pasture-ground trodden by the feet of our neighbor’s cattle. It is a rough concrete tank, unadorned, roofed with an old sheet of corrugated tin. A raw PVC pipe rises out of the ground and pours the contents of an underground spring into the tank, while an equally unprepossessing run-off tube spills the excess into the mud that surrounds the thing. It is nobody’s hippocrene. Still, there it is—an unapologetic example of how water makes life on earth possible.

During the few days we were without running water, we gained some sense of what life is like when an abundance of water cannot be taken for granted. A bathtub filled with water became a resource for flushing with a bucket. A rain barrel became our source of drinking water. Drinking that soft elixir, I began to taste water again and was reminded how before modern times the residents of Istanbul distinguished the taste of water from the city’s different neighborhoods, each quarter vying with the others as to which had the sweetest water. I thought of the victims of drought in Africa, I remembered the jewel-like plots of corn and beans I have seen on the Hopi Reservation in New Mexico, and how cleverly their fields are pieced together down hillsides to take advantage of the scarce water available in that arid country.

~

Three liquid sounds, then, greeted me this morning—rain on the skylight, water flowing from the kitchen taps for the first time in three days, and in my head, a gypsy violin.

I have just inserted the CD into my computer and am listening again to that Romanian gypsy who lives in Paris and plays his violin in Bireli Lagrene’s jazz group. When the violinist, whose name I do not even know, rises to the sublime peak of his solo on the band’s recorded version of “Summertime,” someone else within range of a microphone cries out ecstatically “Oh” or “Ah” in French or Romany or Romanian. Imagine Django Reinhardt, Stefane Grappelli, and le Jazz Hot transplanted into the present, having retained all of Django and Grappelli’s drive and brilliance and joie de vivre but having absorbed everything that has happened in jazz and popular music from the 1920s until now.

When I was in Istanbul during the jazz festival two summers ago, a friend, the Ottoman historian Caroline Finkel, took me to Babylon, a jazz club on a narrow street in Asmalimescit, a bohemian neighborhood in Beyoglu—or Pera, to use its old Constantinopolitan name. Caroline is a transplanted Scot who lives in Kuzguncuk, on the Asian side of Istanbul. Asmalimescit is tucked away in that part of the city in whose narrow, winding streets the Greek, Jewish, Armenian, European, and Levantine merchants lived during Ottoman times, in Art Nouveau apartment buildings with elegant ironwork on their balconies. The night we ventured down to Beyoglu, Istanbul had just experienced one of the powerful thunderstorms that attack the city occasionally, and our taxi ploughed through flooded streets as we drove down along the Bosphorus to reach Babylon.

I had not seen a configuration of musicians quite like the one that Bireli Lagrene assembled that evening. There was no drummer. The acoustic bass player stood at the back of the stage and shepherded the group. Lagrene, the lead guitarist, sat in front flanked by two rhythm guitar players. Two! They never played anything fancy, they just laid down a solid, strummed base for the band’s music and served as a kind of Greek chorus for the brilliance of the lead guitarist and my man, the violinist. What they were playing reinforced the chord structure as well as the beat, and gave the music a solid bottom both rhythmically and harmonically. On songs with a 4/4 rhythmic structure, they strummed away four to the bar, the way the banjo would play in early New Orleans jazz. The violinist was the oldest man in the group. His physique suggested that he seldom missed a meal and as he played he sweated profusely.

The band played jazz standards and swing and tunes from the Bebop repertoire. Clearly they had grown up on American music, because they quoted everything from “Old Man River” to the “Rhapsody in Blue” to the opening riffs of “In the Midnight Hour” by Wilson Pickett. They played their own version of Jimi Hendrix’s “Purple Haze” as a lead-in to a blistering rendition of Dizzy Gillespie’s classic “Salt Peanuts.” Bireli Lagrene then changed the mood and effortlessly executed arpeggios straight out of Segovia. One of the rhythm guitarists sang a syrupy love song in French with atrocious lyrics. They played “Laura,” which began life as the theme song of an American movie from the 1940s—but I suspect I was the only one in Babylon who knew that. Toward the end of the long evening the bass player even put on shades and came to the front of the stage to sing, in barely comprehensible English, “Blue Suede Shoes.” Whatever they played, from the sublime to the ridiculous, from the familiar to the outrageous, flowed in a way that made me realize that by stepping in out of the rain that evening, I had simply made a transition from one form of liquidity to another, just as rain and water from the kitchen faucets and the violin solo from “Summertime” had blended in my mind when I woke up this morning.

~

It occurs to me that I am writing in praise of a quality at once so basic and so elusive that I am hard-pressed to find a word for it. “Hybridity” and “eclecticism” come to mind. The thesaurus is a guide not only to words but to ideas; and when I try to make a start by looking up the word “hybrid,” I find that Roget records it under “mixture,” and takes a rather disapproving tone, listing it with the following gallimaufry of words:

cross-breed, mongrel; half-blood, half-breed, half-caste; mestizo, mustee; Eurasian, Cape-coloured, mulatto; quadroon, octaroon; sambo, griff, griffin; mule, hinny.

This list constitutes a musty little museum of British racial nastiness from an earlier era. That my edition of Roget is out-dated is suggested by the fact that Microsoft Word’s spell-check turns up its nose at five of these words, underlining them in red as soon as I type them in. Don’t even ask me what a griff is, or a hinny. I’m not sure I want to know. Roget seems to speak for that way of thinking that abhors change, puts its money into bonds, gets very nervous when miscegenation is mentioned, and argues for what it regards as purity—on behalf, as Yeats puts it, of the “bankers, schoolmasters, and clergymen / The martyrs call the world.”

~

What I am arguing for here might be called impurity by the world I have invoked above. Historians of the music tell us that jazz first began to be heard in New Orleans—a city whose culture is beautifully evoked by those enthralling words “mulatto,” “quadroon,” “octaroon” with their hint of taboos and family secrets and the keys to an apartment on the other side of town. It began to be played when African musicians got their hands on European instruments like the cornet, trombone, tuba, snare drum, and clarinet, and bent the notes and rhythms of European and American marches to resemble the music of the countries they had been abducted from. Jazz may be the most human of all musics, because like the human race itself, jazz is all about adaptation.

That night in Babylon, Caroline and I had found our way, in the polyglot city of Istanbul, right to the heart of Pera with its ethnic mixture that goes back, seemingly, to the beginnings of the civilized era—an American and a Scot transported by a gypsy violinist from Romania who earns his living in Paris playing jazz. My guide to this musical awakening would have to be a gypsy— wouldn’t he?— from the ancient, feared, and despised tribe of Romany. More than a million of their number were exterminated by the Nazis, but still they park their raffish caravans by the sides of roads all over Europe, tell fortunes, run a thriving car-boot business in electronic equipment, irritate the citizenry of several nations, and flock once a year to the shrine of les Saintes Maries de la Mer in the Aigues Mortes region of Provence to pay tribute to the Black Maria who sailed there, according to legend, from the Holy Land in a little boat with Mary Magdalene and Mary the Mother of God.

~

A hot summer in Ireland, a dry reservoir. The rivers of Babylon, the waters of Sliabh na mBan. The rainstorm that fills our kitchen taps this morning is but a few drops from the deluge that drowned New Orleans—the city where jazz was born, swamped by the waters of the Mississippi. In the meantime there is the life of what may be called the soul. For that entity, music is as basic and essential as water.

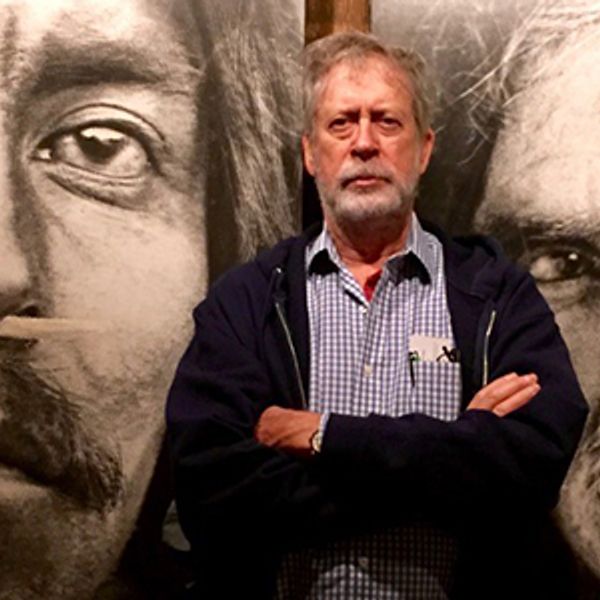

Richard Tillinghast

Richard Tillinghast has published twelve books of poetry and five of creative nonfiction. His most recent nonfiction publication is Journeys into the Mind of the World: A Book of Places (University of Tennessee Press, 2017). He lived in Ireland for six years before moving back to the U.S. in 2011. He now divides the year between Hawaii and Tennessee. (updated 4/2020)