Lia Purpura, Decaying Wood (detail), featured in AGNI 102

The Moral Thing

In April 1986 I went to see the Woody Allen movie Hannah and Her Sisters. The movie was funny, was also very well acted. But I remember that, when I came out of the theater, I felt empty, unclean. Yes, unclean. The movie was about relationships—sisters and sisters, husbands and wives, children and parents. But the people in the movie were for me too “hip,” too “cool.” Even the parents were the same way. They played the piano, they sang songs, but they were not the complete parents that I had seen or wanted to see: fragile, old, soothing, with something deeper about them.

I went home and took a shower. Yes, a shower. Then I went to my bookshelf and picked up a book I had read more than once: Tolstoy’s War and Peace. I turned to some pages at random about one of the main characters, Pierre, and read for forty-five minutes or so. Little by little, I felt whole again, safe. I felt that the world around me, or my own world, was not disintegrating—at least not yet.

I mention this incident because I have learned over the years that, for me, for better or worse, writing is in some ways a moral activity. Why did Tolstoy “save” me on that night? Is it because his world is somehow “deeper,” “cleaner”? Is it because his families are more like the families I grew up with as a child in India? Is it because his world somehow has a sacred, a moral component that I felt more comfortable with—something that the secular, too-secular (and self-absorbed?) world of the movie lacked?

I know that moral and not-moral are relative terms. I also know that people have their own aesthetics for writing (or for filmmaking) and some may dismiss the very use of the word “moral.” But for me, the world of Tolstoy—and also Dostoevsky—has something, just something, that the secular Woody Allen movie did not have. By a moral world I do not mean one that is preachy or didactic. That kind of world, and certainly that kind of writing, I learned long ago just does not work. Writing, and certainly fiction, has to be more subtle, delicate. It has to show or create worlds, and then let people experience and decide for themselves (what Philip Sidney so nicely called “the speaking picture of poesy”). But the world of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, and of a handful of others, has for me a deeper component—family? country? God? compassion?—that the world of Woody Allen’s movie did not have.

There is for me a second, and related, point. In the incident that I cite, the “moral” world of someone else comforted me, “saved” me. I have found something related in my own writing as well. I have learned that if my everyday life is “moral” (or just less self-absorbed?), other things happen. My own writing is better. To be sure, I am not moral in order to be a better writer. But one just seems to lead to the other.

I think, for example, about my trips to India. I don’t think that it is a coincidence that some of my best writing came after three extended trips, many years apart, to India. On each of those months-long trips, I saw a lot and I saw India not as a tourist but from the inside. All good material for writing. But, for me, just as important—or more important—was that I also took care of family and other matters; I was, at least in small ways, a “good” person. So why did the good writing come? It came because I was now worthy to write about what I had seen, or about anything else.

Of course writing is not all seriousness. Far from it. It is also fun, play, the simple joy of words. But for me being worthy to write is also important. People may or may not like what I say or how I say it. But for me that is such a secondary point. The real point is that as long as I am a “good” person (or at least not completely bad), a “worthy” person (or at least not completely unworthy), I feel that I can pick up a pen and at least give it a try.

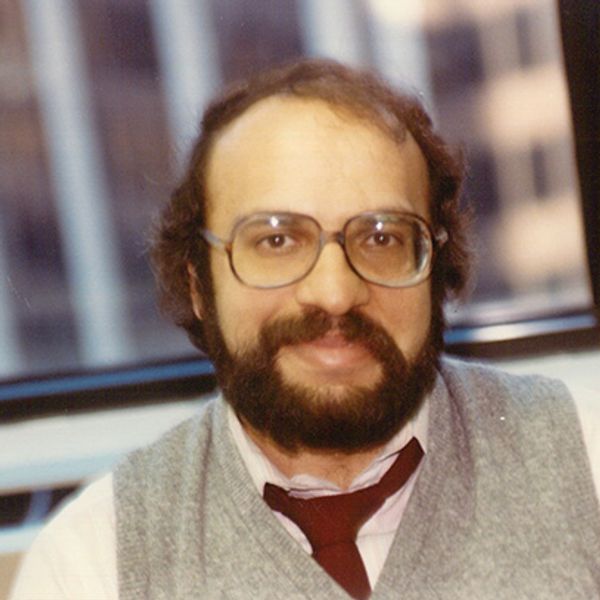

Bipin Aurora

Bipin Aurora has worked as an economist, an energy analyst, and a systems analyst. A collection of his stories, Notes of a Mediocre Man: Stories of India and America, was recently published by Guernica Editions (Canada). His stories have appeared in Glimmer Train, Michigan Quarterly Review, Southwest Review, Prairie Schooner, Witness, Boulevard, and AGNI. (updated 2/2019)