Lia Purpura, Decaying Wood (detail), featured in AGNI 102

Poetry Is Dissent

Poetry is political. Period. It has often been remarked that the so-called “apolitical” poem, the objet d’art, is of course political in its acceptance of the status quo. But while I agree with that view, that’s not quite what I’m getting at here. I believe poetry is political because a poet is always both working with and straining against language. That may seem like a truism, and you may ask “What’s political about that?” Well, for starters, the question of what to accept about how the world is represented in words, and what to reject. In some respects it is a poet’s duty to reject the verbal and rhetorical formulations of his or her moment in time. In other words, a poet is always on a quest for originality, which is not a question of trying not to sound like anyone else, a question of what these days is called “branding,” but a return to the great storehouse of language, to see what can be found there that is useful and true to this moment.

The part of me engaged in that process is the oldest part of me—or maybe I should say the youngest since I started doing it before I can remember anything else.

As a child, words come from a world that was there before you arrived, and you presume, because you must, that there is some correlation between the words and the things and actions and qualities for which they stand. This is the original suspension of disbelief required to acquire language in the first place. And then you go about choosing among the words offered. You try to match the right one with the right thing. You try to say it correctly. You test out the words on other people, usually your parents. Sometimes they think you’re cute, other times they threaten to wash out your mouth with soap!

But soon enough and before you’re even aware of it, you are toughening your spirit on the successive disappointments that you suffer as you learn, again and again, that the words are inadequate. You must find new ones, or combine them in a new way. Many, if not most people, make some peace with the inadequacy of language. I think what makes a person a poet (whether they write in verse or prose) is an abiding commitment to try again, all the while knowing that it is in the nature of language, and of the essence of the whole enterprise, that you will fail.

This is, at heart, a moral commitment, or so I believe, because one of the reasons words have come to disappoint has to do with their deliberate misuse, with their having been poisoned by dishonesty. Here is where I could rant about the ubiquity of advertisers’ and politicians’ designs on us, but it is enough, I think, to simply make the point.

Let me give you a favorite poem of mine, by the great Polish poet Zbigniew Herbert, as a way of describing the act, the ethical and political act, of writing poetry:

A KNOCKER

by Zbigniew Herbert

translated by Czeslaw Milosz and Peter Dale Scott

There are those who grow

gardens in their heads

paths lead from their hair

to sunny and white cities

it’s easy for them to write

they close their eyes

immediately schools of images

stream down from their foreheads

my imagination

is a piece of board

my sole instrument

is a wooden stick

I strike the board

it answers me

yes—yes

no—no

for others the green bell of a tree

the blue bell of water

I have a knocker

from unprotected gardens

I thump on the board

and it prompts me

with the moralist’s dry poem

yes—yes

no—no

Maybe in another time, a time when the world had not been poisoned by a century of genocides and mechanized murder, and before the continuing threat of ecocide, a poet could trust his or her culture’s assumptions about what it means to be good, or powerful, or heroic, or simply human. We do not live in a time like that. And so, we are “moralists” or ought to be, as Herbert unapologetically suggests he is. But it is not the finger-wagging moralism of the self-righteous Herbert’s talking about here; it is instead the weighing of words, and a rigorous attention to how these same words have been used before. Because the discourses of the past have brought us to a sorry spiritual state, we can take nothing for granted, nor can we be silent.

Here’s a recent poem of my own — not great, way too simple, but at least short—that asks a similar question about the poet’s relation to the received world:

PERPLEXITY

In my seventh decade

I have not been able to decide

if we have made a mess of everything

because we have turned away

from what the old stories, poems, rituals

sought to preserve by teaching us,

or if we’ve learned those lessons all too well.

Though I’ve railed against Caesar

and raged against the gods,

I am still unable to decide.

If, as poets, we do not fear the misrepresentation of the world, if we do not guard against it, work against it when hunched over the page, then what are we doing? What is being accomplished, and whom does it serve?

It seems to me that poets are of little value who aren’t trying to see through the fog of stereotypes, untruths, half-truths, and alienating narratives that profit a few at the expense of the rest of us. How do we address the racism, or racialized oppression, that has deeply injured our ability to see one another clearly in America? Why should we continue, as writers, to acquiesce in our own infantilization, as if literature were a playground where what happens is of no consequence in the world?

Here’s how the post-WWII critic George Steiner put it “…any thesis that would, either theoretically or practically, put literature and the arts beyond good and evil is spurious. The archaic torso in Rilke’s famous poem says to us ‘change your life.’ So does any poem, novel, play, painting, musical composition, worth meeting.”

And yet, without beauty—in the case of poetry the satisfying and pleasurable play of language, the bodily, erotic tongue caressing the thrilled ear—the soul remains asleep while the intellect goes on chewing its flavorless daily bread. I’m reminded of Yeats’ comment that some poets have pulpits but no altars and others have altars but no pulpit—his version of Aristotle’s charge to the poet to both “delight and instruct.” The temptation is to try to oppose the pulpit-less deco-poets by leaning way out over your own pulpit with an excoriating index finger in the air. But the real alternative is to enact the poem in beauty’s sanctuary, the heart thereby opened to hear words that challenge, inform, and refresh us in the struggle for a just future.

Far from being a luxury, poetry is the essential medium. It is because poetry is handmade, because it does not require a great deal of money to perform its artistry and effect its influence, that it can save us. Most people find poets archaic, quaint, maybe charming, like candle-light. But think how useful candles are when the power goes out. And think about the gathering storm, and the darkness that has begun to fall.

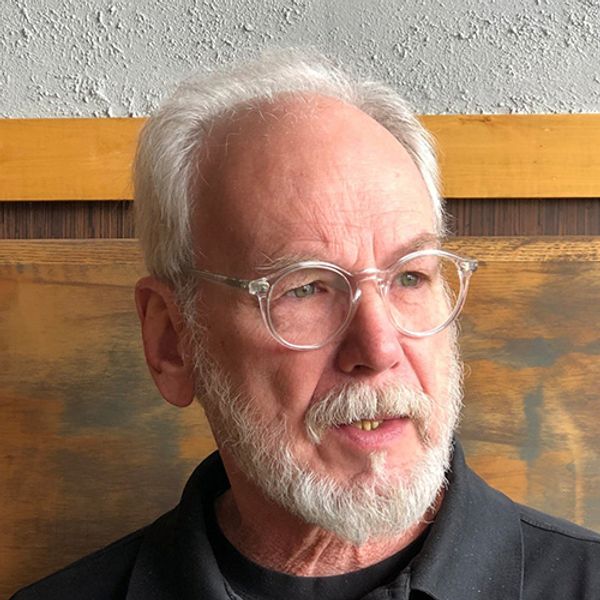

Richard Hoffman

Richard Hoffman is the author of seven books, including the celebrated Half the House: a Memoir, recently published in a Twentieth-Anniversary Edition (New Rivers Press, 2015), and the memoir Love & Fury (Beacon Press, 2014). In addition to the collection Interference and Other Stories, he has published four volumes of poetry: Without Paradise; Gold Star Road, winner of the Barrow Street Pres Poetry Prize and the Sheila Motton Award from The New England Poetry Club; Emblem; and Noon until Night. His work, both prose and verse, has appeared regularly for the past forty years in such journals as AGNI, Barrow Street, Consequence, Harvard Review, The Hudson Review, The Literary Review, Poetry, Witness, and elsewhere. A former chair of PEN New England, he is senior writer in residence at Emerson College and adjunct assistant professor of creative writing at Columbia University. (updated 10/2018)