I received your long letter of complaint today. I welcomed it, for I too once rebelled against my father. The story of how my father carried me for forty years should begin by acknowledging that I didn’t always look over his shoulder. I slept down the hall from my parents, for example, in a bed my father encircled with white pickets. The fence was not high, but it kept me on the mattress. Most nights when overcome with restlessness I walked on my knees from pillows to foot of my bed, back and forth till I collapsed into sleep. This was something I never wanted my father to see. Our experiences were so merged, I needed this knee-walking to establish a semblance of independent self.

I became more adventuresome when puberty hit. My impulse to walk became so strong that I raised myself to my knees and balanced along the wall at the head of the bed. Three a.m. Silence. Summer. Air conditioning. Electricity. A car far off. Heat lightning. Within all this near-soundlessness, I stood on one knee, then rose to my feet. That was all I did that night. And then after months of journeys on foot back and forth across the length of the bed, I used my reading lamp for support, eased myself over the sharp pickets, and stepped for the first time on my bedroom floor.

I used my reading lamp for support, eased myself over the sharp pickets, and stepped for the first time on my bedroom floor.

Not enough can be made of this moment. Nearly fifty years ago. Bare feet on glossy floorboards. It was like Wilbur and Orville’s first flight. Those first steps I took around my room, I did not disturb a pencil on my desk, afraid my father might deduce I walked at night.

I became more bold in my teens. When my father put the son-sling down outside the bathroom door, I walked the hallway, did a little dance, whatever came to mind, until I heard the toilet flush and slipped back into the son-sling. My mother knew all about my secret, for I confessed my ability to stand and walk, told her how it had been hard-won at night. When my father went out without me after my home-schooling lessons, I walked the house, spoke to my mother face to face, but when my father’s car entered the garage, I threw myself to the couch and awaited my return to the son-sling.

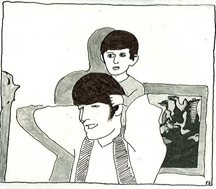

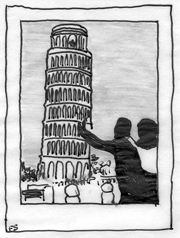

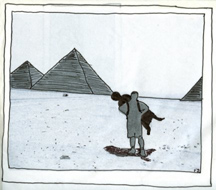

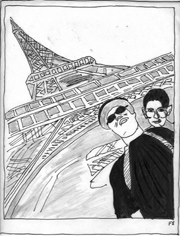

I blossomed late as a man, understandably. Every encounter was as unnatural as could be, and there were many encounters, for my father carried me to other countries. Tucked away in storage I recently found an old family photo album, selections from which I’ve traced for inclusion with this letter. The photographs are of my father and me at ages three, seven, nine, thirteen, on and on, ages twenty, thirty, on my fortieth birthday. I will enclose tracings of us at the Eiffel Tower, the Leaning Tower of Pisa, the Pyramids of Giza. I have never been able to render facial expressions, not even on tracing paper, but if I had sent the original images, you would have noticed how my father is all smiles as he endures my weight in that waterproof, durable, poly-blend hybrid of messenger bag and hammock (attractively crisscrossed with reflective tape–a touch my mother added for safety’s sake).

are of my father and me at ages three, seven, nine, thirteen, on and on, ages twenty, thirty, on my fortieth birthday. I will enclose tracings of us at the Eiffel Tower, the Leaning Tower of Pisa, the Pyramids of Giza. I have never been able to render facial expressions, not even on tracing paper, but if I had sent the original images, you would have noticed how my father is all smiles as he endures my weight in that waterproof, durable, poly-blend hybrid of messenger bag and hammock (attractively crisscrossed with reflective tape–a touch my mother added for safety’s sake).

As you can see from the tracings, the photographs absolutely exist, but why would a man, even one as strong as my father, do such a thing to his son? Why strap one’s only child into a hi-tech hammock-like harness? Why not let me live a normal life?

but why would a man, even one as strong as my father, do such a thing to his son? Why strap one’s only child into a hi-tech hammock-like harness? Why not let me live a normal life?

My secretive knee-walking sessions might make you think I longed to rebel, but I rarely considered my father’s carrying impulse malevolent or absurd. From an early age, I respected my father’s need to do what he did.

The last line of your letter, after a rampage of complaints and accusations, states that you hope we reconcile in time for your wedding–but first, you must understand that my father was not a monster. I walked secretly when I could, yes, but I considered myself blessed when carried. I peered over his shoulder as he taught me what I know of the world. It is essential to understand the respect I had for him, the allegiance: I honored my father. Prisoners fall in love with their captors, and I was no different. Plus, being carried everywhere is enviable, really, if you think about it, as you must think about it if you’re interested in respecting what lies within us all: me, your grandfather, your great-grandfather, and–whether you like it or not–you.

My father died a year before your birth, but he, Herman Spitz, was not a ruthless man. Carrying me had made his torso look like that of the noblest elk. His legs seemed intended to propel caravanning camels. His back was as sturdy as the shell of an ancient sea turtle. He looked fit. Healthy. Smooth skinned. Hair black as volcanic rock–as hard, too, in later years, thanks to styling gel. And his strength increased year after year as he bore my final weight of 130 pounds.

It wasn’t all wonderful, however. My father’s presence in front of me was so constant (I am embarrassed to admit the following detail) that sometimes I would see a paperboy and identify with his newspapers. I’d envy the toss through open air, the slap and skid on pavement. I envied the dispersal, the unaccompanied entrance into a foreign household. I imagined being laid upon a table, analyzed, then discarded. At low points I would have traded my life for a moment lived as a newspaper. I know that last line sounds ridiculous, but it meant something to me. I needed the fantasy of all those words in print across my skin, so contemporary, so functional, so temporary. Instead, it was me and my father for forty years.

You’ve received thousands of letters from me throughout your life. Short notes here and there. Tri-weekly e-mails more recently. But never a long and informative letter that clarifies why I raised you as I did. Now that you have graduated from college, support yourself in the city, and will be a married man in less than a month, I hope you understand that I did what I did for a reason, and I hope the following story about my grandfather–your great-grandfather–makes it clear why I communicated via notes of encouragement and censure, and why for the past decade I relied so heavily on the walkie-talkies.

Johan Spitz was a steely soldier sprinting across a gruesome battlefield, carrying a wounded buddy who seemed to the carrier’s senses filled with things horrendously sulfurous. My grandfather would have loved to have ended that horror, that stench. Oh how he’d have loved to have dropped his buddy! But he held on, delivering the wounded from danger to safety, whereupon his friend promptly died.

Imagine finding out that carrying someone from danger to safety had contributed to his death, as though such heroism were murder. Imagine how this might have affected our battle-rattled relative Johan Spitz, home and settled into a stable existence, taking his newborn son in his arms–light of his life, a perfect-pink cherub, so unlike his wounded buddy–until memory (physical as well as psychological) forces the precious little package to the floor and no one can do a damn thing about the kid dropped on his head who thereafter grows unlifted and pledges not to repeat his father’s failure: he will lift weights and work construction in the summer–mortar work–whatever it takes so his own son never knows the ground. My father promised that as long as he lived he’d keep his son airborne. Carry him no different than Atlas did the world.

All my years with my father are documented in the family album. I’ve enclosed tracings (authenticated with my initials) as photographic proof, and yet, the authenticity of my tracings you might find questionable (perhaps unreliable to the point of unbelievable). You might think I drew more than I traced. You might find the whole tracing business suspicious in general. I would prefer if you inferred my intentions, however, rather than be handfed a rationale re: why I traced the originals, when, with much less effort, I could have dropped photocopies in the mail. I would prefer if you responded to this letter with another letter letting me know why you think I’ve opted for this tracing process: such a response would show your respect. But I suppose it is possible you have no idea why I traced. Perhaps you think I have lost my mind? Or that as sole family historian I have spun a nightmare to serve my purpose by swelling your sympathy? That I write this fiction to make you suffer for the accusatorily cold-hearted impertinence of your letter? That I allowed you to enjoy the unlimited, unfettered, wholly natural movement that was withheld from me for forty years, but now, after receiving your long letter of complaint, I compose this response to make you feel deserving of no more than a cage in the attic best suited for some gutter-tongued cockatiel?

If I have begun to lose anything, it is my patience more than my mind. I traced the photographs because I wanted you to sense the distance I felt from the world. I was no older than ten when my father made me trace the works of Heinrich von Kleist, Gottfried Keller, and Adalbert Stifter. Pages and pages of dense syntactical convolution, lovingly translated from the nineteenth century German, removed my thoughts even farther from those around me–quite something considering the son-sling’s effect on my psyche by the time my father instituted the tracing regimen. Throughout my twenties and thirties, clandestine ambulation aside, I experienced everything from behind the black-lacquered dome of my father’s skull. My father took photographs, and often asked strangers to photograph us. These fragmentary souvenirs I have traced with pencil and pen to reveal the distance from reality that marks our family’s lives.

If my grandfather represents an immediate experience of reality, my father the photograph, and I the tracing, then who, my son, are you?

The disbeliever? The shredder? Or the confetti itself?

But thanks to the way the tracings remove you from reality, you might not believe my grandfather’s story about carrying a man for miles through smoke and gunfire and strewn humanity gone mad with bloodlust to conquer a bit of territory, all compelled by an international trade dispute or an assassination somewhere in a Balkan hellhole that leads to trenches and bayonets and biplanes and young men who not long before were safe at home, awestruck by the half-dozen automobiles in town, consumed by candy stores, shoes coated in the dust of unpaved streets, salivating at the sight of bare feminine ankles and wrists, ankles and wrists: all of it impossible, especially since no photographic evidence proves that your great-grandfather made it through without a single visible scar, all of it impossible and inseparable from our heritage, a force that made Johan Spitz drop his son on his head, that in turn compelled Herman to carry me in ever-larger slings until we perfected the final version’s specifications for my twentieth birthday.

So many impossibilities, if you think about it, as I am now thinking about it through the semi-therapeutic process of writing this letter. Impossible that my father carried me for decades–that is, until the day twenty-five years ago when I presented my father with a whispered impossibility nearly as implausible as the story about one man carrying another on his back, only to have the carried man die as soon as the carrier put him down.

Or so the story goes. One we can believe or not. But the point, I think, is that our belief does not matter. What’s important is that my father believed these stories so entirely, so thoroughly, that he had not much space within him for anything else. My father’s belief in his own father’s story filled him so entirely that there was no way my father could believe in the somewhat similar pairing of the crucified and the cross, surely the world’s most infamous interdependent duo (one I think you’ve taken too much to heart lately), those stars of an implausible story that hundreds of millions have believed in no differently than I believe in paper and pen, another infamous interdependent duo with which I write this letter to someone who deserves to see in the clearest possible words why it is I’ve done what I’ve done with you, why I so thoroughly believed in my father’s belief of his father’s story, so my only son might one day believe the story I tell now and better understand what it is he may do with his own children (assuming) and what these children may do with their own children (assuming), and so on (assuming).

I believe in paper and pen, another infamous interdependent duo with which I write this letter to someone who deserves to see in the clearest possible words why it is I’ve done what I’ve done with you, why I so thoroughly believed in my father’s belief of his father’s story, so my only son might one day believe the story I tell now and better understand what it is he may do with his own children (assuming) and what these children may do with their own children (assuming), and so on (assuming).

As for now, enclosed with this letter and the traced photographs you will have found the instructions for operating the replacement of your old walkie-talkie. The new walkie-talkie, as you will see on Tuesday or Wednesday (Monday being a postal holiday), is not a walkie-talkie at all but the newest-fangled videophone. It’s no bigger than your cell phone, so it’ll be an improvement on those clunky old machines we used. The videophone will let you see and hear me, at any moment, just as I’ll be able to see and hear you. Please take the time to review the instructions, considering their great expense and purported “extraordinary functionality.”

Your whole life you have known me as a correspondent. While living under the same roof, I always thought it essential for our emotional and psychological stabilities to keep my distance, secure in my locked study. You can understand now why I considered such distance necessary, and you should realize that I always had your well-being in mind. Now, thanks to the new videophones, we’ll always be apart and always together. Distance, they say, makes the heart grow fonder. Without it, I would die, not physically, perhaps, but spiritually, whatever that might mean to you.

You say the distance between us seems unbridgeable. Your letter describes a time when you tried to reach me in my study, how you knocked on the locked door, how you pounded and wailed and sobbed, how you learned to pick the lock, how when you finally managed to open the door I forced you into the corridor and slammed the door in your face. Opening the door only to have it slammed in your face, above all other rebukes, you say, iced your desire to connect with me ever again. You say your adolescence was a tyranny of miniscule pen strokes on fortune-cookie–sized slips of paper, that you still dream about these notes, that all my carefully composed words of encouragement, castigation, advice, and warning you read as death sentences, each eroding whatever capacity you had within to love me. You say that talking on the walkie-talkies I integrated into our relationship after you picked the lock to my study was like communicating with someone from beyond the grave. You couldn’t believe my voice belonged to a living, breathing human being, let alone the man who should introduce you to the wonders of the world. You accuse me of making your mother leave me to work at an Alabaman orphanage, where she met your stepfather, who established himself as a model of manliness in your life by forcing you to submit to Christ and the cross. Yet I do not recall a word of protest from you. I remember glee when you related your grades via walkie-talkie. I remember Christmas mornings when you woke me with frantic pleading to listen as you unwrapped presents. I remember your mother telling me how you stored the notes I wrote in a piggy bank next to your bed, as though such slips of carefully composed communication were more valuable than coins. You say your mother has been a stabilizing constant in your life, as she was in mine, mostly, and I agree that yes I have been more like a satellite transmitting paternal programming from some impossible distance. I recognize your right to complain. I respect it. And I hope this letter and the videophones enable a new connection, one we never would have imagined if we’d lived in the age of smoke signals.

The videophones achieve an ideal of long-distance communications, yet if you switch yours off and throw it in the river, the connection that runs through you and me and my father and his father and so on (all the way back) is not something you can discard. You’re always connected, whether you like it or not. There’s nothing you can do about it. You can’t drop what’s inside you. But we can use these videophones to forge a relationship we will not regret after I die. I realize that last statement was morbid, perhaps manipulative, too. Maybe it’s unfair to talk at this point about death and regret, the imminence of one and the inevitability of the other. But I want you to know that I realize how important a step it was for you to take when you sent that long handwritten letter of complaint. I am an expert on taking steps, having done so in secret for forty years.

But why did I wait forty years to whisper what I did into my father’s ear? Why did I need forty years to declare independence? I still see that day so clearly. The day I met your mother, my father and I were making our way up Witherspoon’s slight incline toward its concluding intersection at Nassau Street. There we saw turn the corner an adult female of an aspect unusual for the area (middle-aged, fresh-faced, non-white) who we’d soon learn was a half-Haitian named Hattie. Deep in the background, Nassau Hall sprawled as stately and as ivy-strewn as it had for nearly two and a half centuries, protected by an endless gate of black spears. In the foreground, father and son saw this woman come around the corner, her hair concealed in a tight silo of ruby-red batik. She exchanged a stunned look–a joyful one!–with my half of the father-son combo, a look that swaddled the baby-faced, gray-haired son in compassion, a look charged by recent years au pairing in our preppie hometown, a look as radiant as the sun that made it through the maples lining Witherspoon Street, a light in which she saw me more as ideal ward than man-child out for a piggyback.

The look we exchanged caused a disturbance so strong it forced me to risk ridicule and make eyes at certain beauty as it passed on the street. I risked ridicule when I did such a thing because, other than the softball-style cheeks I had at the time, I was, as you can discern in some of the tracings, altogether avian (swan-necked, eagle-beaked, owl-eyed, bat-eared). I risked ridicule because I was glowingly pale thanks to my father’s insistence on SPF 45 sunscreen. And also I risked ridicule because I lay horizontally behind my father’s shoulders in a high-tech sling.

Of exposure to needy children your mother had more than her share, but otherwise she was hopelessly alone when it counted. And staring down her fortieth year, she did not have too many dreams left, but whenever she looked at Nassau Hall, the word orphanage splattered across the windshield of her thought. Hundreds of sorry heads and grimy hands popped from each of the building’s windows. Orphans on the brain, Hattie had, until she turned the corner and saw the sight that changed her life:

The moment she saw me slung across my father’s back she knew she would adopt me as ward and mate, for I was her ideal orphan.

And so, twenty-five years ago, once Hattie turned the corner, I told him. Quietly at first, I told him. Perched on his back, I told him. Into his left ear, I told him. Quietly at first, then louder, I told him. Until the telling was all my father could hear.

Maybe he had finally tired of carrying me? Maybe whatever it was that obsessed him for forty years gave way when confronted with Hattie’s compassion? Whatever it was, there was no struggle. I staggered beside him before I found my stride and chased after Hattie.

Relieved of the burden he carried on his back–and perhaps of the affliction within him, too–my father withered. His burden and his affliction, inside and out, had propelled him since he’d been dropped on his head. After all those years enduring my weight, he collapsed less than a week after Hattie turned the corner and entered our lives.

The passion that runs through your letter shows that you are blessed with the potential to understand the complexities you’ve inherited. As such, you should understand that I realize I overcorrected for my father’s overcorrection of how his father raised him. I have often considered easing my maximum-distance stance, but when I entertain such options my chest tightens, the veins in my arms constrict, and an unpleasant pulsation commences in my neck. I respect such an extreme reaction. Maybe I could overcome it with counseling, but I doubt our family’s vicious pendulum can ever be stopped. My grandfather Johan Spitz put his buddy down and the wounded buddy died. My father put me down and he soon died, too. If we were to embrace at your wedding, I wonder what might happen to me?

I ask you to understand these words as a plea. I ask you to respect what I have never controlled, the way neither my father nor grandfather controlled what they did. Perhaps one day, I will hoist you on my shoulders, even if such action passes my burden wholly to you when I am struck dead. Whether this letter eases or enrages, I hope you acknowledge the forces within us. And I hope you put your mother on the videophone at the wedding. Let her know I miss her. As I miss you. And know that–as always–I apologize for my weakness, my weirdness, my wrenching need. I look forward to carrying on our correspondence via the small screen, or if you prefer, through the old-fashioned medium of the written word. Love, I realize, is the only word this response ever required, so I’ll write it twice more (once for each of us)–love, love–before entering that era of vulnerability wherein I await your reply.